The army that opposed American independence has its roots in the 17th century, with the formation of the “New Model Army” as a permanent standing army during the English Civil War. In the century that followed the size of the army grew and shrank depending on the circumstances, and by 1775 it numbered around 48,000 men. By European standards the British Army was extremely small—the French maintained a force nearly four times larger—but many in Britain did not see the need for a large army. For one, there was political resistance to maintaining a large army. Many British subjects looked back to the time of the New Model Army and saw how a professional force could be used to oppress the people. In addition to the dangers it posed to liberty, a standing army was also extremely expensive to maintain during peacetime. As an island nation at the heart of a colonial empire, the navy was vastly more important to maintaining British trade and projecting British power. The main role of the peacetime army was to guard the colonial frontiers and to maintain control over Ireland.

The British Army of the late 18th century was a volunteer force. Unlike the navy, there was no impressment or conscription into the army, a point of pride for most British subjects. The majority of men who volunteered for service were farm laborers or tradesmen who were out of work. Life in the army promised steady pay, regular meals, and a way to escape grinding poverty. Before the war, enlistment in the army was a lifelong commitment, but during the war, shorter-term enlistments of several years were introduced to encourage recruitment. Recruits were generally young, averaging in their early 20s, and were drawn from all over Britain and Ireland. By the eve of the American Revolution, the majority of the men in the ranks had never seen active military service and were not battle-hardened veterans. The exception were many of the army’s non-commissioned officers. These men formed the backbone of the regiment and were often veterans of many years or even decades of service.

As the war in America dragged on the British Army expanded rapidly. At least 50,000 soldiers fought in America, with many more serving in the West Indies, Europe, and India. Britain struggled to meet these manpower needs with volunteer enlistments and soon turned to other means. Two short periods of impressment were tried during the war, in which unemployed men could be taken into the army, but these acts proved to be very unpopular. By 1780 the measures had been rescinded after only bringing in a few thousand men. A much more reliable source of manpower came from the German states of the Holy Roman Empire. King George III was also the elector of Hanover, giving him close dynastic and social ties to the rulers of the German states. It was a long-standing practice for some of the rulers to rent out their armies as a source of royal income, and more than 30,000 Germans were hired to take part in the American Revolution. Commonly referred to as Hessians, these men came from a number of different states, including Hesse-Kassel, Brunswick, and Ansbach-Bayreuth. Another source of manpower came from American Loyalists looking to enlist. Some 25,000 Americans served the crown, some in British regiments, but most in “provincial” regiments with other Loyalists.

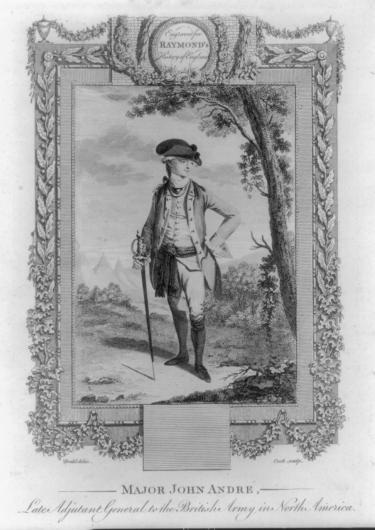

The men leading the army were drawn from a drastically different social class. The majority of army officers came from the upper classes of British society, and were often the younger, non-inheriting sons of well to do families. With the exception of Colonels, who were appointed by the king, officer’s commissions were purchased. A retiring officer would offer to sell his commission to the next most senior officer, and if he refused then it would be offered to the next officer and so on in order of seniority. If an officer died or was killed in battle then his commission was usually filled strictly by seniority. The cost of an officer’s commission was paid to the government, who held it as a sort of bond. If the officer was dismissed dishonorably he lost the money, which induced many officers to take the responsibility seriously. About 2/3rds of the British officer corps in the Revolutionary War purchased their commissions. The remainder achieved their rank through other means. The king directly appointed some, while others were promoted up from the ranks of the senior non-commissioned officers. Promotion was more meritocratic in the engineers and artillery, as these arms of the service required skill and extensive knowledge of mathematics and science. Regardless of how they first gained their commission, the British officer corps during the Revolutionary War was experienced, with most senior officers having several decades of experience.

The basic building block of the British Army was the battalion or regiment. The two terms were used somewhat interchangeably in the 18th century, as most regiments consisted of a single battalion (although there was a handful made up of 2 or more battalions). Each battalion consisted of ten companies for a total strength (on paper at least) of 642 officers and men. Eight of the companies were known as “battalion” or “hat” companies and were made up of standard infantry troops. The remaining companies were the “flank” companies made up of specialized soldiers. On the right of the battalion was the grenadier company. Grenadiers were chosen from the largest and most physically strong and imposing men of the battalion and were used as shock troops for assaulting enemy positions. In earlier times the grenadiers would literally carry explosives that they lobbed at the enemy, but by the Revolutionary War, this was no longer widely practiced. On the left flank was a company of light infantry. Unlike the grenadiers, light troops were chosen for their speed, agility, marksmanship, and ability to operate independently. Their role on the battlefield was to skirmish with the enemy from behind cover, provide reconnaissance, and protect the flanks of the army. During the Revolutionary War, most grenadier and light companies were stripped from their battalion and amalgamated into separate battalions made up entirely of other grenadier or light companies.

Seven of the ten companies were commanded by captains, while the remainder were nominally commanded by the regiment’s colonel, lieutenant-colonel, and major. Under each captain was a lieutenant and an ensign (or second lieutenant in the flank companies), and these men were collectively known as the company officers. Above the company officers were the field officers of the regiment - the colonel, lieutenant colonel, and the major. Each regiment was commanded by a colonel, appointed by the king. Colonels had a large amount of discretion over the outfitting, uniforming, and training of their regiments - so much so that the British Army is best understood as a collection of individual regiments rather than a single, top-down entity. The rank of colonel was a largely administrative position, and they rarely served in the field with their regiments. Instead, colonels were likely to be given positions within the army hierarchy, often as generals. One example of this is Lord Cornwallis. While serving as a general and commander of the army in the south he was also the colonel of the 33rd Regiment. General John Burgoyne, commander of the Saratoga campaign, was a colonel in the 16th Light Dragoons. The rank of general was also sometimes temporarily bestowed on colonels while on campaign, as was the case with Brigadier General Simon Fraser, who was also lieutenant colonel of the 24th Regiment.

During wartime regiments were temporarily grouped into brigades, usually consisting of two to four regiments under the command of a field officer holding the temporary rank of brigadier. Several brigades could then be combined into a division if the army was large enough. There was no permanent set command structure in the British Army at the time, so the organization of brigades and divisions varied greatly over the course of the war.

Further Reading:

- The British Army in North America 1775-1783 (men at Arms Series, 39) By: Robin May

- The Men Who Lost America: British Leadership, the American Revolution, and the Fate of the Empire By: Andrew Jackson O'Shaughnessy

- With Zeal and With Bayonets Only: The British Army on Campaign in North America, 1775-1783 By: Matthew H. Spring

We can save three remarkable battlefield sites if we can raise $201,500. Every dollar you can donate to this cause will be multiplied by $23.80.

Related Battles

149

868

75

270

1,300

587

93

300

330

1,135

1,900

324

90

1,018

325

381