William Wells

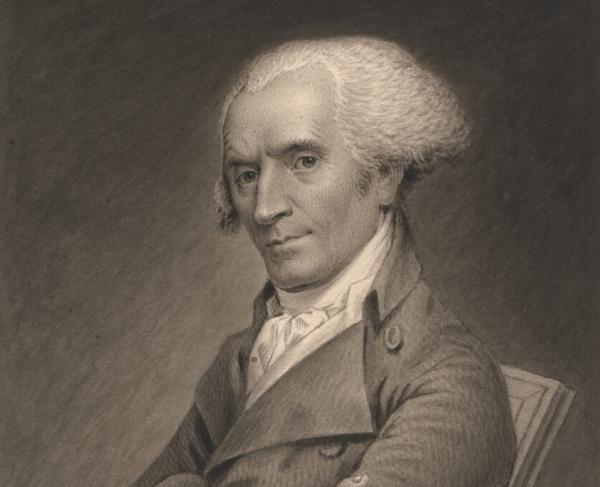

William Wells was a key participant in many of the important events on the Ohio Valley Frontier; his divided loyalties epitomize the conflicting values of the period. In 1784, at age thirteen, Wells was captured near Louisville by the Miami and taken to an Eel River village in Indiana. The boy became a warrior, married Sweet Breeze, the daughter of Little Turtle, and fought with that great war chief in Harmar’s Defeat (1790) (present Fort Wayne), and the Battle of the Wabash (1791) (present Fort Recovery, Ohio); this was the biggest victory the Indians ever won against the U.S. army. Wells (Miami name Blacksnake) led a group of snipers that took out the artillery. Of the 1,200 hundred soldiers involved, over 900 were casualties. After visiting his family in Louisville in 1792, Wells switched sides to assist Rufus Putnam at a treaty with the Wabash Indians in Vincennes. Impressed by his mastery of Indian languages and customs and his knowledge of the territory below the Great Lakes, Putnam hired Wells to spy on the Indian Confederation led by Little Turtle, Blue Jacket of the Shawnee, and Buckongahelas of the Delaware. Under Little Turtle’s protection, Wells was the only American present at these councils on the Maumee River where the Indians hotly debated what to do following their victory on the Wabash. He was not able, however, to report back to the Americans until September of 1793.

General Anthony Wayne in Cincinnati examined Wells “very minutely” for three days and found his information “authentic.” He was “very well informed & most certainly in the confidence of the Indians, from his prowess in war…& took a conspicuous part against us on the fatal 4th of November 1791.” Wayne hired him to scout for the Legion, the several thousand men preparing to avenge the army’s previous defeats. Generals Harmar and St. Clair, lacking competent scouts, had marched into ambushes and disaster. Wells changed that equation; he hired experienced frontiersmen, some former captives, and led them on a series of dangerous missions to scout out Indian positions and take prisoners to question. This was the most celebrated part of Wells’ remarkable career, once the subject of many tales, both tall and true, about his exploits.

When Wells encountered a war party, he sent an unheeded warning to Fort Recovery. Great Lakes warriors assaulted the walls, took heavy casualties, and went home. Later, Wells and a few men rode into a Delaware camp pretending to be Indians, their ruse was spotted, and Wells was shot in the wrist, thus ending his scouting but not his usefulness. After Wayne was informed of a large force concealed in fallen timber ahead, Wells advised him to wait until the fasting warriors returned to their camps for food. When the Legion changed with fixed bayonets, the depleted warrior defenses were routed.

Following Wayne’s victory at Fallen Timbers (1794), Wells convinced Indian nations to visit Fort Greenville in 1795 to negotiate. He served as the interpreter between his commander-in-chief and his father-in-law; in the treaty the Confederation ceded all but the northwest corner of Ohio. The next year Wells was an interpreter for a delegation of chiefs who went to Philadelphia to meet President Washington. In recognition of his service, Wells became Indian Agent to the Miami at Fort Wayne, a position he held for a decade. Agent Wells took Little Turtle to confer with President Adams in Philadelphia and Jefferson in Washington, where he demanded more support for his people. Wells and Little Turtle, suspecting Jefferson’s motives, gave grudging support to his civilization program as well as the land-grabbing treaties imposed by Governor William Henry Harrison.

The government viewed Wells and Little Turtle as both essential and untrustworthy. After helping Harrison to mandate unfair treaties, Wells then advised the nations to resist them. Finally, in 1809, he was fired but then rehired by Harrison. Wells warned about the threat posed by Tecumseh and his brother The Prophet. After Harrison routed The Prophet’s followers at Tippecanoe in 1811, the frontier became more dangerous. When Pottawatomie warriors surrounded Fort Dearborn (present Chicago) in August of 1812 Wells went to the rescue, negotiating an evacuation. A mile away from the fort, the 96 people were ambushed, sixty were killed on the spot, including Wells, who died a heroic death defending women and children. Streets in central Chicago and Fort Wayne are named in his honor.