Stones River

The Battle of Stones River

Murfreesboro

The day after Christmas, 1862, Maj. Gen. William S. Rosecrans' Army of the Cumberland left Nashville and marched toward Confederate Gen. Braxton Bragg's Army of Tennessee at Murfreesboro, 30 miles to the south. Rosecrans had about 80,000 men under his command, yet he left 40,000 men in and around Nashville to guard his communication and supply routes -- nearly evening his odds against Bragg. Rebel cavalry troopers under Colonel John Hunt Morgan operated around Nashville, keeping Yankee cavalry busy but not effecting Rosecrans’ move south. The Federal army generally followed the route of the Nashville Turnpike as it crossed the mid-Tennessee countryside toward Chattanooga. Confederate cavalry under Brig. Gen. Joseph Wheeler harassed the column as it moved south, capturing four wagon trains and 1,000 Yankee prisoners on December 29.

The two armies gathered on the banks of Stones River on the evening of December 30. Rosecrans’ 41,000-man army on the northwest bank of the river was organized into three infantry corps (or wings) with three divisions each. On the right, Maj. Gen. Alexander McCook’s corps filled the farm fields south of the turnpike and west of Murfreesboro. Continuing to the north, in the center, Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas’ corps was posted near the turnpike where it crossed the Nashville and Chattanooga Railroad. On the Union left, Maj. Gen. Thomas L. Crittenden’s men covered the Stones River fords to the north.

Facing the Federals were Bragg’s 35,000 men arranged into two corps of infantry. On the Confederate left, two divisions of Maj. Gen. William J. Hardee’s corps faced the Yankee right flank with their backs to Stones River. Hardee’s third division under Maj. Gen. John C. Breckenridge was posted north of the turnpike, behind the river and awkwardly splitting Hardee’s command. Between Breckenridge and the remainder of Hardee’s corps was the corps of Lieut. Gen. Leonidas Polk, facing the Union center.

The night of December 30 was cold, wet, and miserable for the soldiers in the line on both sides. Sometime before the evening tattoo, one of the Union’s regimental bands struck up “Yankee Doodle” and then “Hail Columbia.” As the music drifted across the field, the Confederate soldiers listened quietly. Then, one of their bands answered, playing “Dixie.” This friendly exchange of music continued for a time until a Federal band started to play the bittersweet sounds of “Home, Sweet Home.” Within minutes, a Southern band joined in, and the bands played together in what was a unique expression of mutual longing for home and family. Finally, more and more bands joined in and the collective musical forces of both armies played the tune together. One soldier from Tennessee remembered that “after our bands had ceased playing, we could hear the sweet refrain as it died away on the cool frosty air.”

New Year’s Eve dawned cold and gray, with fog and drizzle obscuring the field of battle. On the Union left, Crittenden’s men prepared to move across Stone’s River and begin the assault on Bragg’s right. As a result, Rosecrans was nearby and focused on Crittenden’s preparations. To the south along Thomas’ line, it was quiet for the most part and men prepared their breakfasts. However, on the far right near his juncture with McCook’s troops, one of McCook’s divisions was preparing to fight. That division was led by General Philip Sheridan. During the night, one of Sheridan’s brigade commanders, General Joshua Sill, brought him word that his pickets had spotted a considerable amount of Confederate activity to his front, and it appeared they were moving toward the far right of the Union line. The two men rode to wake General McCook and tell him what had been observed. McCook quickly dismissed them and the possible threat and went back to sleep.

Sheridan remained disturbed and, upon his return to his division’s lines, ordered his staff to quietly rouse the men, give them a quick breakfast, and then get them into line of battle. Sheridan next walked the line personally to ensure every regiment was in-place and ready for what he suspected might be a Confederate attack. As the deep black of night steadily turned to a gloomy, opaque, misty gray, McCook received additional reports of movement along his line. Finally, he issued orders to his other divisions to make preparations for an attack, but it was too little and too late.

Minutes later, the soldiers on McCook’s far-right saw dark, shadowy figures quietly approaching through the dense mist. Suddenly, the figures merged into a long, seemingly unending line, and the morning calm was suddenly broken by the shrill cry of the Rebel yell. That yell came from 11,000 Confederates under William J. Hardee. They smashed into the Federal right flank, shooting men down as they ate their breakfast with their rifles out of reach. There was a brief flurry of hand-to-hand fighting, but McCook’s men began to flee in panic towards the rear and the Nashville Turnpike, three miles away. Some Federal regiments tried to make a stand but, unsupported and isolated, they also soon broke for the rear. Within 30 minutes, two of McCook’s brigades ceased to exist.

Nearby, Sheridan’s division along with Sill’s fought back and, with the loss of those two brigades, the Union right had bent back inward. Four Confederate brigades attacked the new flank but they stubbornly held. Eventually, they too gave ground, but Bragg’s attack was starting to lose momentum. Then, Polk began his attack on the Union center, in an attempt to prevent any support from going to McCook, but this assault was conducted in a piecemeal fashion and George Thomas’ men turned them back, inflicting a great number of casualties.

Meanwhile, Rosecrans could hear the steady thumping of artillery to his right along with a steady cascade of rifle fire. However, despite the bad reports coming in, he did not seem concerned. Finally, when McCook sent a message pleading for reinforcements, Rosecrans realized the magnitude of the disaster on the Union right. He ordered Crittenden to cease his advance and sent troops to bolster Sheridan and Sill.

The fighting on the Union right continued unabated as Hardee pressed both Sheridan and Sill back. Soon, dead horses and soldiers, smashed artillery, and burning wagon littered the fields northwest of Murfreesboro. Because the ground contained so much limestone, blood did not soak into the soil. Rather, it gathered on the ground in pools, both large and small, dotting the landscape and adding a ghoulish quality to an already nightmarish scene.

Sheridan’s division fought especially hard as the former went everywhere to personally direct his men. This soon became a necessity, as he lost all three of his brigade commanders before noon. By 10:00 a.m., the Federal line had been pushed back into a V-shape, with the left side facing east and the right facing west. Sheridan’s division manned the apex of this reformed line and, given that they formed a salient, the Confederate attacks now came from both sides. He organized a skillful withdrawal, all the while maintaining a tight hold on the Union units on either side. And, while this V-shaped line was vulnerable, it also allowed Rosecrans to quickly shift his forces wherever they were needed, which he did with great energy and skill.

That morning, Rosecrans exercised a brand of personal courage and leadership typically reserved for corps and division commanders. He rode all about the battlefield, asking for reports, giving succinct orders, and providing encouragement where needed, and it was much need on that cold, bloody morning. On the left, he rode up to Colonel William Price, whose brigade was positioned along the river to prevent any Confederate crossing attempts. Rosecrans shouted at Price, “Will you hold this ford?” Price replied, honestly, “I will try, sir!” Rosecrans shouted even louder, “Will you hold this ford?” Price replied, “I will die right here, sir!” Still not satisfied, Rosecrans shouted once more, his voice filled with emotion, “Will you hold this ford?” The young colonel responded, “Yes, sir!”

By midday, the Union apex had shifted to an area known as the Round Forest, a small hill of limestone punctuated by dense cedar groves, and the right was aligning along the Nashville Turnpike. But Rosecrans continued to strengthen his line, sending units wherever they were needed most, no matter what brigade or division they belonged to. As Hardee’s assault lost all its energy due to a steadily mounting casualty toll, Bragg ordered Polk to renew his attacks, focusing on the Round Forest. There, his men were met by a staggering punch issued by Colonel William Hazen’s brigade. Polk continued to hammer away at Hazen and Rosecrans poured reinforcements into what became known as Hell’s Half-Acre. By 1:00 p.m., Polk’s men were spent and Bragg called for Breckinridge to send him four fresh brigades from across the river.

As Bragg waited on Breckinridge’s men, Rosecrans and Thomas further reinforced the Round Forest, bringing in every available piece of artillery. At 4:00 p.m., the first two of Breckinridge’s brigades moved into the line opposite the Round Forest and awaited Polk’s orders, as well as the arrival of the remaining two brigades. However, under pressure from Bragg, Polk elected not to wait and launched the assault with two instead of four brigades. The men marched smartly across the field, now littered with hundreds of bodies from the previous attacks. The newly arrived Union artillery quickly opened fire, blasting huge gaps in the advancing lines, but they kept coming forward. When the Confederate line reached a range of only 50 yards, Hazen ordered his infantry to open fire. The results were devastating. Breckinridge’s men fell by the dozens and the entire attacking line staggered to a halt, then broke to the rear amid a hail of rifle and artillery fire. One regiment lost 47 percent of its men and many others suffered more than 30 percent casualties.

One would think this could have convinced Bragg of the futility of another attack, but he refused to change his mind. When Breckinridge’s other two brigades arrived, he ordered Polk to sacrifice them as well. It is little wonder that some officers questioned Bragg’s sanity at this point. By now, the Federal artillery in the Round Forest numbered more than 50 guns and, as the assault was renewed, their crews fired as fast as they could reload. The second Confederate attack got no farther than its predecessor and the results were nearly identical. Nothing was gained and nothing was proven except for the bravery of Breckinridge’s men.

At one point, Rosecrans and his staff were close to the action, observing the defense of the Round Forest. With him was Colonel Julius Garesché, his aide and his closest friend from his cadet days at West Point. In fact, it was Garesché who convinced him to convert to Catholicism. As the fighting raged in front of them, a round of solid shot from a Confederate cannon roared past within inches of the commanding general’s head. As it flew by him, it hit Garesché in the face. He was immediately decapitated, and his headless body stayed in the saddle for 20 paces before pitching off the horse to the ground. Rosecrans rode on, his uniform covered with Garesché’s blood, unaware of what happened behind him. Later, when he was told about his friend’s death, he quietly said, “Brave men die in battle. Let us push on.” However, no matter his words, Rosecrans was deeply affected by his comrade’s death. After the battle, he carefully cut the buttons from his uniform and placed them in an envelope marked, “Buttons I wore the day Garesché was killed.” He would carry that envelope with him for the rest of his life.

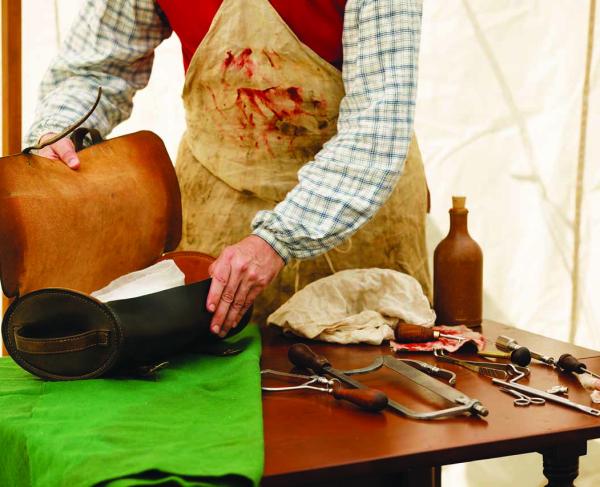

With sunset, the sounds of battle quickly faded and gave way to the moaning of the wounded. The cold, dark, blustery night was filled with the sight of lanterns floating between the two lines, as men from both sides attended to the wounded and dying.

Rosecrans held a meeting of his commanders to discuss the next day’s action. Old Rosy asked them if they should retreat, but at that moment, George Thomas, who had been napping, suddenly awoke, looked around him with a fierce gaze and said, “This army does not retreat.” With that, the issue was settled and the Army of the Cumberland would stay and fight.

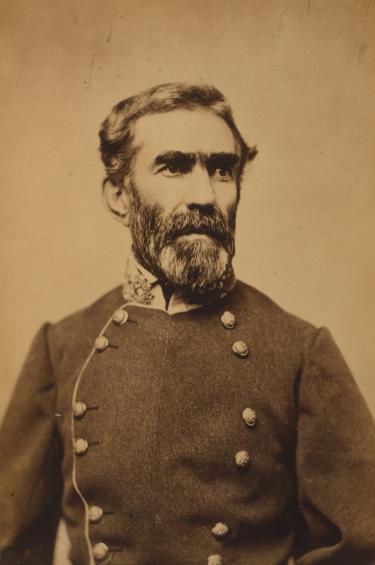

Bragg, however, was flush with victory. He was certain Rosecrans would limp back to Nashville during the night, and he sent an urgent telegram to Jefferson Davis trumpeting his success: “The enemy has yielded his strong position and is falling back. God has granted us a happy New Year.” So convinced was Bragg of his victory, he went to bed that night without making a single adjustment to his line of battle. As far as he was concerned, the Battle of Stone’s River was over.

When the dawn of the new year of 1863 arrived, Bragg was greeted not by the sight of an empty field before him, but, rather, by the same blue lines of infantry that had been there the night before. Bragg stood paralyzed with shock and when his generals came to him seeking orders, he had none to give. Instead, he sunk into a sort of mental lethargy, issuing orders for menial tasks as opposed to crafting a new strategy. Later in the day, he ordered Breckinridge to resume his original position across the river, but that was the extent of his leadership for the day. That night, he continued to seek signs that Rosecrans was finally withdrawing, but they did not come—the Union army was not simply going to go away as he hoped.

The next morning, Bragg, upon finding the enemy still in his front, ordered an artillery bombardment to see if it might provoke a response. He wanted to see just how committed Rosecrans was to holding his position. When the Federal artillery answered in kind and more so, he had his answer. After fretting about a course of action, he decided to try to place his own artillery on high ground east of the river in front of Breckinridge. This would allow him to pour a potentially devastating fire into the Union left flank, which might drive Rosecrans out of his positions. Bragg ordered a reconnaissance of the area and, when the scouts returned, they told him that the high ground he wanted for his artillery was already in possession of a Union division. Bragg decided to order Breckinridge to take the ridge and called the Kentuckian to his headquarters. When he was told of his assignment, the former vice president protested in anger, telling Bragg that his men could not possibly take such a strong position. Exhibiting both his intransigence and his dislike for Breckinridge, Bragg told him that his Kentucky soldiers had suffered the least thus far and now it was their turn to prove their worthiness.

Breckinridge again protested the order, telling Bragg that he had personally seen the Federal emplacements and they could not be taken by direct assault. Bragg angrily told him, “Sir, my information is different. I have given an order to attack the enemy and expect it to be obeyed!” With that, the discussion was over.

When Breckinridge returned to his men and told them what had been ordered, General Roger Hanson, commander of the Orphan Brigade, exploded in anger and proposed that he go to the headquarters and shoot General Bragg. Breckinridge prevailed upon him not to do so, and, instead, to go prepare his command for the attack.

At 3:00 p.m., as Breckinridge massed his men for the assault, Rosecrans observed the activity and sent reinforcements across the river. More importantly, he also moved additional artillery onto the west bank of the river, where they could cover the Union defenders. By the time Breckinridge began to move forward, Rosecrans had assembled 58 guns on the high ground facing east.

An hour later, Breckinridge’s men started to advance across nearly 600 yards of open ground into the teeth of a Federal division and a mass of supporting artillery. Despite the heavy defensive fire, the Kentuckians never faltered, moving ever closer, and finally pouring over the Union lines. The blue-clad defenders fell back in disorder and, after 30 minutes of fierce fighting, Breckinridge’s men had accomplished an objective they believed was impossible, but rather than stopping to dig in and hold, they foolishly pressed forward in pursuit of the fleeing Yankees. It proved to be a fatal error.

As soon as the retreating Union troops were out of the way, the 58 Federal guns west of the river opened fire on Breckinridge’s still advancing line. Blasting away at better than 100 rounds per minute all together, they simply slaughtered the Kentuckians. Within minutes, the entire flow of the battle had changed. As the Southerners turned to retreat back up the slope of the hill, Crittenden ordered infantry reserves forward, driving the Orphan Brigade back across the hill they had just taken and into the fields they had just crossed so bravely. Seeing the sad remnant of the Orphan Brigade returning, Breckinridge broke down, sobbing, “My poor Orphans! My poor Orphans! My poor Orphan Brigade! They have cut it to pieces.”

That night, amid another cold, driving rain, Bragg called a meeting of his key commanders. After some spirited discussion, they could not reach a decision on how to proceed. However, on the morning of January 3, Bragg became convinced that his army was beyond its limits, and at 10:00 a.m., he ordered a withdrawal and the Battle of Stone’s River was over, at last.

The battle was hailed as a major victory in Washington, while President Davis and General Bragg suffered not only a defeat, but one made an embarrassment by Bragg’s premature announcement of victory on New Year’s Eve. Middle Tennessee was now lost to the Confederacy, and Lincoln had a victory to counterbalance the recent defeat at Fredericksburg. Bragg remained in command of the Army of Tennessee both because Davis could not stand the loss of face he would suffer if forced to dismiss Bragg, and also because there simply was no one else for the job. Bragg and his commanders continued to fight harder against one another than they ever did against the enemy until he was finally relieved of command following the Union breakout at Chattanooga in November 1863.

For William Rosecrans, Stones River was the high point of his entire career. Even when he later had to relieve Rosecrans of command after Chickamauga, Lincoln remembered the timely victory at Stones River. Writing to Rosecrans after his dismissal from command of the Army of the Cumberland, the president said, “whilst I remember anything, that about the end of last year and the beginning of this, you gave us a hard-earned victory, which, had there been a defeat instead, the nation could scarcely have lived over.”