Music in 18th-century armies was incredibly important to tactics, drills, maneuvers, and esprit de corps. The incorporation of music into the great armies of Europe, performed by instruments such as drums, fifes, bagpipes, bugles, clarinets, and French horns, was a long-standing tradition by the time the century concluded with a new country, the United States of America. Raoul F. Camus, a historian of military music of the American Revolution, argued during its bicentennial that although the European military musical tradition had been well-documented, “For many years it was believed that bands and band music were nonexistent in the Revolutionary period.” Furthermore, Camus stated that many still believed that bands and band music were not authorized in the regular army of the United States until 1834. These ideas could not be further from the historical record, and, as more scholarship on the era has revealed, music in the 18th-century armies that fought in the colonies was vital to the daily lives of the soldiers on and off the battlefield.

Music in armies of the 1700s held five very important roles, some of which overlapped in their purposes. Music served to build and sustain the morale and esprit de corps of any sized fighting unit. This role of music was vital in periods of depressed morale, usually in the wake of severe battlefield defeats, or during inordinate hardships, such as long, hot marches or the grueling conditions of a poorly supplied, cold winter encampment. One of the ways in which this role overlapped with another function of music in the army was its utilization during social or recreational events. Dances, balls, time in a hut or around a campfire, were all ways in which music was used for morale-building as well as letting the men blow off steam from the rigors of a campaign, drill in camp, or the loss of friends and family on the battlefield. More specific to military operations, another use of music was to regulate camp duties, and on the other end of the spectrum, to play its prescribed role in ceremonial functions.

Perhaps the most important role of music in armies of the period was its use in tactics. During the previous centuries, as the size of armies grew, and the advent of gunpowder amplified the sounds of battle, voice commands were no longer able to achieve large-scale command and control. Further still, as battlefield tactics changed toward “mass unit warfare,” keeping large organizational bodies of men moving across terrain and in combat in a systematic and orderly way proved challenging. Here, in all accords, steady, loud, drum cadences became a solution to these operational concerns. Each cadence could signal something different, and the composition of the drum and how it produced sound made it a perfect instrument for use with infantry soldiers. Yet again, this role overlapped as “The addition [of] music to accompany marching serve[d] the triple purpose of keeping the cadence, of encouraging the spirit of the men while marching, and of attracting and entertaining the spectators.”

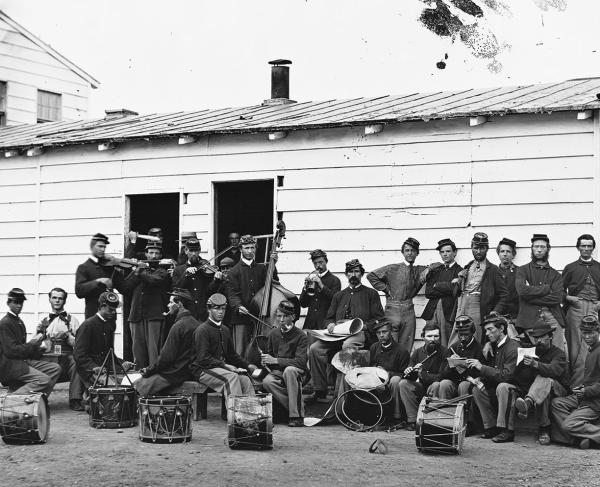

Although music in 18th-century armies played a vital role, all military music was not the same. One form of military music was performed by a “Band of Musick...professional musicians hired by officers to play contrapuntal music at parades, during meals, and for dancing.” Men in the ranks would have had less exposure to this form of military music as did officers and civilians. Soldiers, men in the ranks, were almost continually hearing another form of military music, “field music.” This form of military music utilized musical calls that acted as commands while on the march, in camp, or on the battlefield. The two most important instruments in field music were the fife and drum. Of the two, the drums were significantly more important than the fife, which simply added melodic interest to the drum calls. Drummers, and their instrument, had vast responsibility, not only for the daily routines of the soldiers in camp, but also on the march and in battle.

As the eighteenth century drew closer to war in the colonies, the importance of drums in the European military tradition only deepened. Greater instrumental technique and facility were now required by the demands of the rudiments and cadences. The only way to achieve this was through extended time in practice and training. Educational theory reveals that it is far easier to learn and master new information and skills at younger ages, as well as have the physical facility to accomplish these specific goals. Thus, Bennett Cuthbertson, a military theorist who focused on the functions and operations of a battalion infantry, recommended in 1768, that boys under the age of fourteen be enlisted to be trained as drummers. Preferably, sons of men already in the ranks or orphans, would carry the full responsibility of a private while learning their craft as a drummer, supplementing adult drummers until they could be transitioned to full-time musicians.

Cuthbertson also recommended young boys as fifers as well. Although the theorist replaced the age limitation as applied to drummers with the following about fifers, “As their duty is not very laborious, it matters not how young they are taken, when strong enough to fill the Fife, without endangering their constitutions.” Many fifers entered the musical ranks as young as nine or ten years of age. Unlike the Continental army, which saw more fifers throughout the army in many of the battalions, companies, and regiments, only grenadier companies in the British army allowed fifers according to regulations. In several instances, however, British battalions and companies desiring their own fifers ignored the regulations with some regiments then having a total of four to six fifers.

Music was so essential to command and control both on and off the battlefield that musicians not only needed to be heard, but they also needed to be seen. As such, many 18th century armies had uniform regulations that set their musicians apart from both enlisted and private alike. The distinctive and elaborate dress of the musician enabled the captain of the battalion to find him quickly in the din, smoke, and confusion of battle, and then order him to play certain calls to further instruct those in the ranks what to do. By the time of the Revolutionary War, British drummers could be seen “wearing coats of blue, gray, orange, white, four shades of yellow, two shades of green, two shades of buff, or royal red,” alone, while also carrying a short sword. Their hat was black, made of bearskin, and contained a silver-plated crest of the king’s cypher. In the latter years of the war, the Continental army also adopted this standard, having the coats of drummers and fifers reversed in color. New England soldiers, for example, wore white coats with blue facings, again, making them easily seen during battle to issue orders with calls.

Although music and its role in the military had long been established in the European military traditions by the time of the American Revolution, the disparate colonial troops that later comprised the Continental army took several years to standardize this aspect of their organization. Like the late adoption of different colored uniforms for musicians in the fledgling American army, it took the strong influence of a professional soldier of the European tradition to bring Washington’s musicians up to speed. Upon the arrival of Baron von Steuben to the colonies in September 1777, the former Prussian army officer quickly went to work professionalizing the ranks of Washington’s Continental Army. These patriots not only practiced the art of war, loading and firing their weapons, maneuvering through drills, and working as effective companies within the larger sized regiment, they also learned the effectiveness and usefulness of musicians' roles. All of this was accomplished by Steuben’s steady and constant guidance. Steuben’s regulations for the use of the drum in the Continental army outlined some of the most important activities for the army in camp, on the march, and in battle.

In Washington’s camps after the arrival of Baron von Steuben, soldiers regularly heard “The Reveille,” a drum call for the men to get up for the day. This call also ended challenges by the sentries. Drum calls in camp began at headquarters and were then repeated throughout the entire camp or on the march so all units within the area had heard them. Depending on the orders for the day, another typical drum call under Steuben’s regulations was “The General,” a beat ordering the men to strike tents and prepare to march. Allowing approximately thirty minutes for this order to be followed, “The Assembly” was beaten next, ordering the men to repair to the colors, or fall in. Following the men breaking camp and falling in line, the next drum call was “The March,” commencing the soldiers’ movements. For those men stationed at a fort or occupying quarters in a town, the end of their day was marked with “The Tattoo.” Beat by the drummers at 9:00 pm in the fall and winter months, and 10:00 pm in the spring and summer, it signaled local innkeepers to “turn off the taps,” concluding liquor and beer sales for the day. Drumbeats of a more related nature to combat included “To Arms,” and “Parley.” The former beat alerted the men to take up their weapons and prepare for combat. The latter call was a signal from one enemy combatant to another that a conference was desired. Steuben’s work at Valley Forge and with other units and officers during his tenure with the colonial armies continued to refine these European military music traditions, many that can still be found in the American armed forces today.

With so much emphasis placed on the important role of the musician and the music, they played in 18th-century armies, an examination of their construction and decorative elements should also be noted. Again, because of its wide appeal in visual and written historiography, as well as being commonly associated with the period, it is important to examine at the two most prominent instruments of field music, the drum, and fife. For the British armies that waged war across the colonies, a regulation passed in 1768 required all drums made for military use to be made of wood that was “painted the color of the regiment’s facing, which would also be the color of the drummer’s coat.” Additionally, the king’s cypher and crown, as well as the number of the regiment would also be painted onto the drum’s shell. The drums were carried by British drummers by drum slings or carriages that were worn around the neck. Other aspects of drums of the period can be found in both British and Continental examples, including materials of construction. Again, snare drum shells were wooden, with the heads and frames held together and tightened and loosened with multi-strand rope. This process was facilitated by ears, sewn leather pieces around the ropes. The drumhead itself was primarily made of calfskin, while the snares were made of natural snare gut from lambs. Continental drums were also painted as well, but not with the king’s crown and cypher!

The construction of fifes across both armies was similar as well. Fifes were either made of turned wood, or in some cases, iron. In either material, they were made in a single piece, hollow inside, with an embouchure hole and six finger holes. Also known as a transverse flute, fifes could be played to the left or right horizontally and were usually pitched in Bb. Minor differences between fifes in the two armies were larger bore diameters and different-sized keyholes in English-made versions. Although many fifes used and purchased in the colonies came from England, there were at least two well-known fife makers in the colonies. Sadly, examples of only one of these craftsman's fifes survive.

Music in 18th-century armies was incredibly important to tactics of the period and the overall morale of men who comprised them. However, musical instruments in a military setting was nothing new by the time that century dawned. Music of the great armies of Europe had already been a well-established tradition. Field music, heard in camp, on the march, and in battle, was not the only type of music performed by military musicians, although perhaps it is the most well-known in historiography and popular history. “Bands of Musick” also served important roles, albeit more ceremonial in nature and usually not-to-be-heard by those in the rank and file. In 1976, military and music historian Raoul F. Camus noted the challenge of correcting popular history and a general understanding of music and its relationship to 18th-century armies. Now, as we approach the sestercentennial of those fateful days of 1776, and the years of the American Revolution, perhaps the music of the period’s armies will be back on the frontlines of scholarship and popular imagination, as much as it was on the frontlines during the war’s many engagements.

Further Reading

- Military Music of the American Revolution By: Raoul F. Camus

- Early American Music By: David K Hildebrand

- The Revolutionary Soldier 1775-1783: An Illustrated Sourcebook Authentic Details about Everyday Life for Revolutionary War Soldiers By: Keith Wilbur