“I will have to make the fight on the ground I now occupy.”

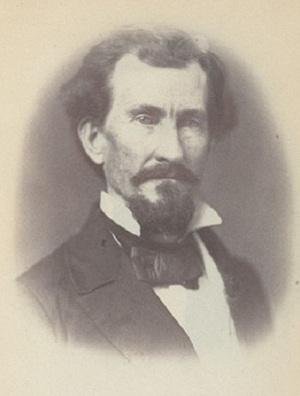

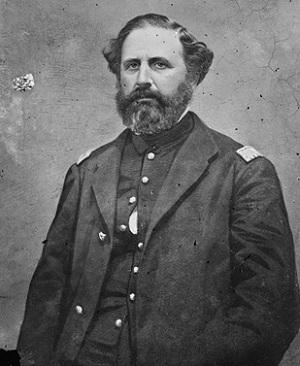

Majer General George B. Crittenden

Old ravines meandered through the chilly landscape. They were filled with dense timber, the ground then rising sharply into scrubby hills, or leveling into farm fields with dark split rail fences. Through it all ran the Cumberland River, much higher and faster than the man on the northern riverbank would like it to be.

Felix Zollicoffer was a dapper man, a former Tennessee journalist and U.S. Congressman who was not foreign to a pistol-duel. He had briefly seen Indian combat as a militia captain in the 1840s. That slim experience won him a brigadier general’s commission in the Confederate Army during the fledgling nation’s scramble to get on a war footing. Here, in southeastern Kentucky in January, 1862, he was the right center of a Confederate strategic line that stretched from the Cumberland Gap to the Mississippi River.

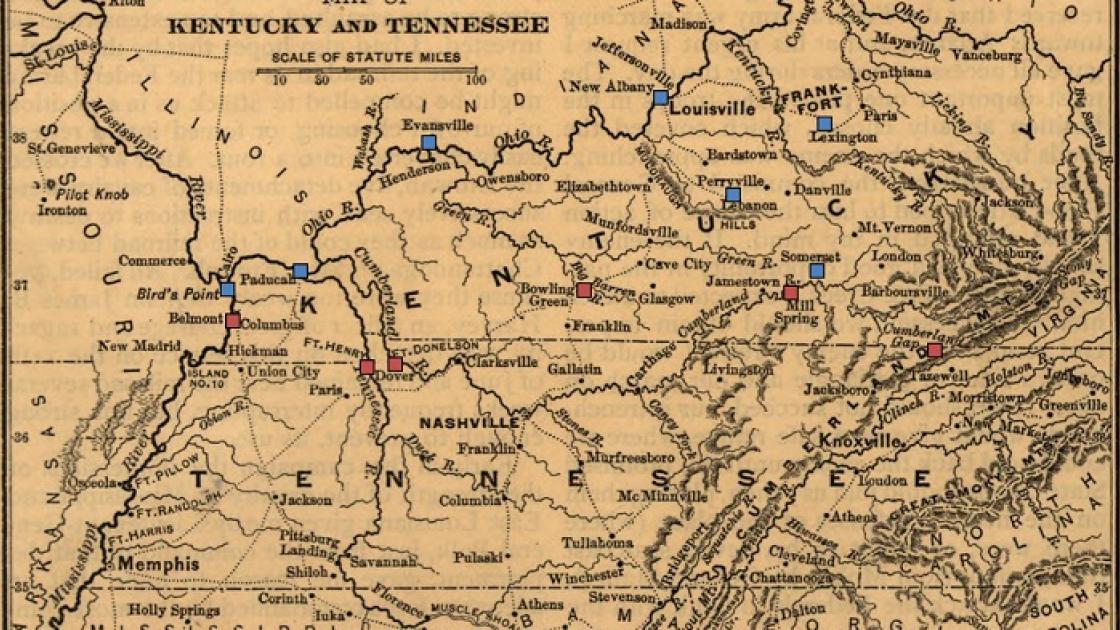

More than 5,000 Southern soldiers were with him, scattered throughout the fortified winter camp that anxious locals referred to as “Zollicoffer’s Den." The camp sat in a horseshoe bend of the Cumberland River, surrounded by water on three sides with a 1,200-foot line of earthworks spanning the fourth.

His fleet sat near the riverbank: a small converted paddle-steamer, the Noble Ellis, and two wooden flat-boats. Several other boats and a pontoon bridge had been swept away by a recent storm. A few days later, Zollicoffer’s superior, Kentucky-born Maj. Gen. George B. Crittenden, had crossed the river to give Zollicoffer a sharp dressing-down. The horseshoe bend was not a fortress, he declared, it was a trap. He had in fact been captured in a similar situation during the Mexican War—nowhere to run with an unfordable river in the rear.

Zollicoffer conceded that ferrying 5,000 soldiers, 12 cannons and all of the army’s horses, wagons, and supplies across the Cumberland with only three rickety boats would be essentially impossible. Union forces were in the area and the cavalry had been skirmishing on-and-off for days. His position was well-known to the enemy. Surely a withdrawal would be discovered and exploited. The Confederate generals estimated that they were facing between 6,000-10,000 Nationals. The thought of a surprise attack by a force that size in the middle of the ferrying operation, the 5,000 Confederates substantially divided on either side of the river with no quick way of crossing to help their comrades, was too bitter to contemplate.

They could continue to fortify—Zollicoffer had been working on that landward-facing line of earthworks during the winter. But Crittenden strongly doubted their effectiveness. Federals could still cross the river and bombard the Southerners from any direction they pleased, rendering the position fundamentally untenable. Unable to move backward, unable to stay where they were, the generals turned their plans toward the attack.

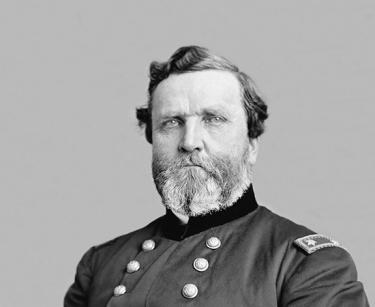

The Union commander was General George Thomas, a mountain-sized Virginian with a clear, calm eye who had chosen Nation over State. He had roughly 4,000 men in his charge—Midwesterners, Kentuckians, and Tennesseans—and was planning an attack of his own from his headquarters in Lebanon, Kentucky. Half of his force was with him in Lebanon, fifty miles (a two or three day march) northwest of Zollicoffer’s Den. The other half was in Somerset, only seven miles northeast of the Confederate position.

Thomas wanted to unite his forces before beginning an offensive. He led his men through heavy rain out of Lebanon, arriving at a hamlet known as Logan’s Crossroads, near Somerset, on January 17. That night, Col. Samuel Carter’s brigade left Somerset and moved towards Logan’s Crossroads, wading through freezing-cold Fishing Creek on the way and not joining Thomas until nearly five the next morning. Another infantry brigade and some cannons stayed behind in Somerset. If the rains kept up, the creek could soon rise so high as to prevent a crossing.

At that moment, that was what Zollicoffer and Crittenden were betting on. Their cavalry scouts had already located the two Union positions. If Fishing Creek would flood, it would give them some cover to surprise and whip the people at Logan’s Crossroads. Col. Carter’s movement was executed in secret and the Confederate generals were unaware of his presence when they sent their attack columns forward at 1 a.m. on January 19.

“Their treasonable colors were seen flaunting in the breeze”

Lieutenant Colonel William C. Kise

The men marched through woods in a dark, driving rainstorm. Zollicoffer’s brigade was in the lead, his cavalry—Kentuckians and Tennesseans—probing in front of his infantry. Behind them General Crittenden rode with William Carroll’s brigade of Alabamians and Tennesseans, and behind them the artillerymen and horses struggled through mud that sank the guns to their axels.

They marched for nine miles before the first shots boomed out from the Federal picket line. The 1st Kentucky Union Cavalry had remained alert and now spoiled the surprise attack. There was a brief exchange of gunfire, Kentucky against Kentucky, that left two of the dismounted pickets wounded, one mortally. They fell back as the Southern horsemen spread out and surged forward.

The firing continued sporadically as they withdrew up the road. Confederate infantry joined the fight after the Nationals made a brief stand at a log cabin. The Southerners took time to form line and stack their blankets and haversacks while under fire from the pickets, who were gaining in strength as the fighting drifted northward.

Zollicoffer’s brigade stretched out into gray and butternut lines, slowed by dense trees and morning fog, and then came forward. The deadly seriousness of the attack was now apparent.

The men of the 10th Indiana could hear the jarring blasts of the skirmishers, sometimes infrequent and sometimes in rapid succession, coming closer. Soon enough, the whole regiment was sent to reinforce the pickets. The heavy air and constant rain kept the acrid black powder smoke low among the trees.

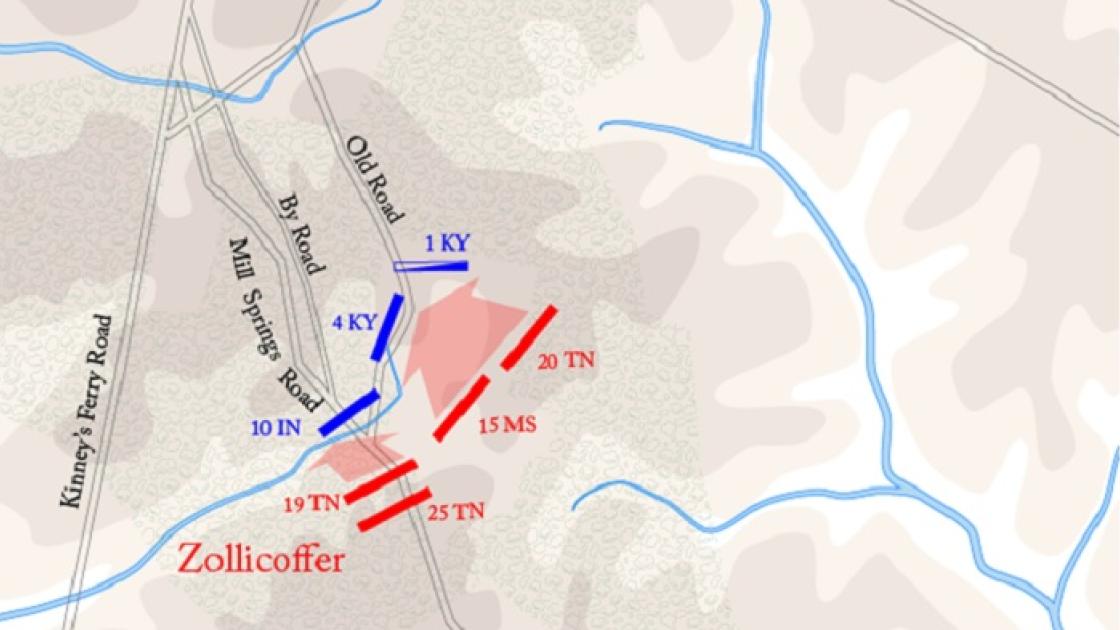

When the 10th Indiana arrived at the front, the battle exploded into a new dimension of fury. The 1st Kentucky Cavalry quickly reformed on the left flank of the infantry. Scattered, harassing musketry turned into rolling volleys as the Indianans took position on a partially wooded hill overlooking the farm fields occupied by Zollicoffer’s brigade.

Through holes in the smoke and rain, the Nationals could plainly see three Confederate regiments, each battle line distinct, moving and firing in the fields below. Leaden messengers began to strike men from the ranks with frightening rapidity.

Zollicoffer led from the front, giving most of his attention to the 19th Tennessee on the far left of his line, and was thus unable to coordinate an overwhelming, all-in-at-once assault that almost certainly would have broken through the Union roadblock on impact. His remaining regimental commanders were left out of his sight and without specific orders, resulting in piecemeal attacks that did not take full advantage of the brigade’s numerical superiority.

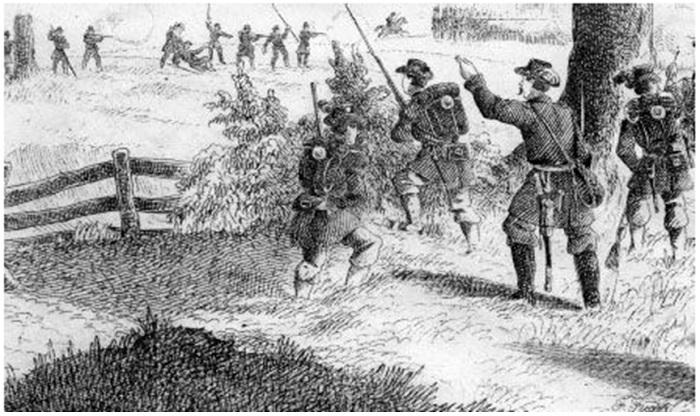

The Federals held out for the better part of an hour before the Confederates managed to use nearby ravines to outflank the position. They withdrew “Indian style,” falling back and firing from tree to tree, using the road as a guide, as more Union troops, Col. Speed S. Fry’s 4th Kentucky Volunteers, began to move to the front.

Fry’s Kentuckians met the 10th Indiana and 1st Kentucky Cavalry at the crest of a ridge just south of the main Federal campground. 240 Indianans formed a new line astride the road. Fry’s 400 deployed behind a split rail fence on their left, facing a belt of cleared ground that dipped quickly into a wooded ravine before rising again into a scrubby ridge some 250 yards down-range. The remaining cavalrymen formed in a cornfield on Fry’s left flank.

“Come forward like men!”

Confederate bullets began to pepper Fry’s position before the battle line was fully formed. The 15th Mississippi pressed forward into the ravine while the 20th Tennessee kept up a covering fire from the ridge. Unable to see anything more than scattered musket flashes through the fog, Fry ordered his men to advance over the fence and down the ravine slope. The Confederate shooting intensified as the Federals moved into the open. Fry quickly realized that he was outnumbered and that behind the fence was a good place to be. He directed a hasty withdrawal which his men executed in style.

Thinking that the withdrawal signified a disorderly retreat, the Mississippians in the ravine unsheathed their long cane-knives and charged uphill after the Kentuckians. The limited visibility worked against them now, and they scrambled to within mere yards of the fence before the deafening boom of a Kentucky volley tore through the smoke and fog. “Our bullets were sent with unerring aim -- many rebels shot in the forehead, breast, and stomach,” remembered one Union infantryman.

The surviving Mississippians tumbled back into the ravine as Fry shouted exhortations to his men along the fence. The 20th Tennessee began to move into the ravine as well, crouching and crawling to avoid the Federal fire. At this, Fry climbed onto a fence rail and shook his fist at the Confederates, demanding that they stand and “come forward like men!”

The secessionists charged again, with portions of the 20th Tennessee sweeping eastward to strike the Union cavalrymen as the 15th Mississippi hit Fry’s infantry. The attackers reached the split rails and for desperate moments the two sides poured point-blank musketry into each other from either side of the fence. The Confederates fell back, reformed, charged again, and were repulsed again. They took cover in the ravine and kept up a hot firefight with the Kentuckians.

“I then wheeled, fired, and killed him myself”

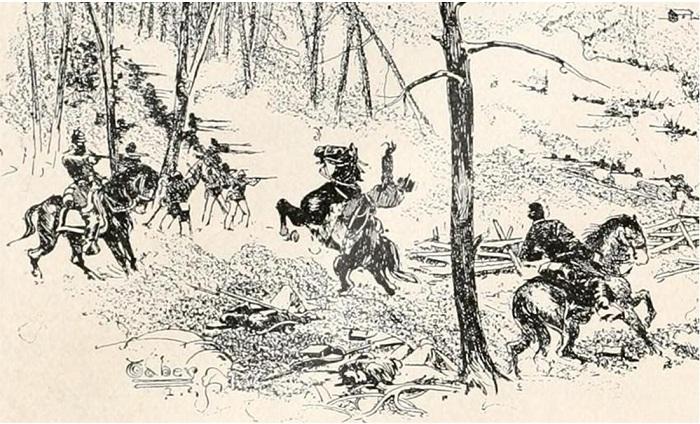

Gen. Zollicoffer was still hanging near the 19th Tennessee during the struggle for the fence. The 19th was fighting the remnants of the 10th Indiana on the road, but the Southerners could barely see the force opposing them. When a new group of men came into view roughly 100 yards ahead and to the right, Zollicoffer thought that they represented the left flank of the 15th Mississippi, although the direction of their shooting came dangerously close to the 19th Tennessee. The general, concerned about friendly fire and perhaps recognizing that his offensive was sputtering, rode through the smoke to reconnect with the wayward regiment and renew the attack.

The mysterious soldiers were not Mississippians—they belonged to Fry’s 4th Kentucky Volunteers. Fry himself rode out to greet Zollicoffer, whose Confederate uniform was concealed by a long rain jacket. Zollicoffer drew rein about thirty yards from the Union line and the two officers came so close that their knees touched.

“We must not shoot our own men,” Zollicoffer told the Union colonel. Fry was plainly wearing a Federal uniform, but Zollicoffer was near-sighted. Or perhaps he had realized his mistake, and was now bluffing for time.

“Of course not,” Fry replied, “I would not shoot our own men intentionally.” He did not recognize Zollicoffer, but thought him to be an unmet officer from Sam Carter’s brigade, which had only recently arrived.

“Those are our own men.” Zollicoffer pointed towards the 19th Tennessee.

Now somewhat suspicious, Fry rode twenty or thirty yards past Zollicoffer to examine the situation for himself. As he peered through the smoke, a Confederate staff officer dashed from behind a tree and called to Zollicoffer, “it’s the enemy, General!”

The unknown officer drew his pistol and shot Fry’s horse before turning to make his escape. A Kentucky rifleman shot him down. Zollicoffer pulled out his pistol and emptied it in Fry’s direction. Unscathed, Fry shouted, “that’s your game, is it?” and returned fire with his Colt Navy .36, striking Zollicoffer in the chest. Two more bullets from the Kentucky infantry killed him.

Fry jumped off of his horse and ran back to his regiment calling for more men to shore up the threatened flank. The men of the 19th Tennessee, frightened by the death of their general, withdrew when the Union reinforcements arrived. The 25th Tennessee advanced to take their place and the battle continued.

News of Zollicoffer’s death came as a shock to General Crittenden. Credible sources report both he and General Carroll had been drinking heavily since the night before. Crittenden ordered Carroll to move his brigade toward the sound of guns.

Carroll’s men reinforced and reinvigorated the Confederate assault. The Southerners surged up the road, managing to briefly recapture Zollicoffer’s body, and new charges were launched against the fence. The 4th Kentucky endured another point-blank shoot-out, bayoneting the attackers when ammunition ran low, but Fry’s men were finally beginning to waver.

“He died bravely charging on the enemy”

With the Confederate force now fully committed, General George Thomas prepared a counterattack. He directed Sam Carter’s rookie brigade to support the 1st Kentucky Cavalry in the cornfield on his far left flank and sent the 2nd Minnesota Infantry to relieve the 4th Kentucky at the fenceline in the center. He deployed the 9th Ohio Volunteers, his most experienced regiment, on the road on his right flank.

The 2nd Minnesota was nearing the fence when men of the 4th Kentucky started streaming back out of the smoke, breaking through files and throwing the formation into some confusion. Pushing forward through the thick underbrush, the reinforcements were suddenly greeted by a terrifying sight: a line of Confederate muskets resting firmly on the fence in front of them, aimed to kill.

“Forward!” screamed their colonel, Horatio Van Cleve, as the line erupted in flame and smoke and buck and ball shot ripped through the Minnesotans—their first experience with enemy fire. The blue-clad infantrymen scrambled over rocks and roots and crashed through thick bushes. They returned fire and dodged behind trees to reload, less than thirty yards from the enemy line and moving forward.

And then the Nationals were at the fence. Muskets were swung like clubs and the Mississippians did fearful work with their cane-knives. One man had his beard singed off by the discharge of an enemy gun at close range. Union private Albert Parker saw his brother die, a bayonet run through his stomach.

The struggle for the fence continued until Col. Carter’s brigade swept in from the east, outflanking the Confederates and threatening to capture their ravine. Most of the Southerners fled to the south and west, toward the road. The Minnesotans leapt the fence and charged after them. Tennessee Lieutenant Bailie Peyton held his ground, emptying his pistol, killing Lt. Tenebroeck Strout before being killed himself.

“With a wild shout and one volley, we turned their whole army into a stampede”

As the easternmost Confederate positions collapsed, Colonel Robert McCook prepared his 9th Ohio Volunteers to spearhead the Union counterattack in the west. The regiment, mostly populated by German immigrants, veterans of European wars, was widely considered to be one of the best in Thomas’s army. From the edge of the woods, the Ohioans could see Confederates posted in a log house, stable, and corn-crib and behind a fence across the cleared field in front of them.

The fortified Confederates poured fire into McCook’s men as they advanced into the open. McCook himself took a load of buck and ball to the right leg—a severe and painful wound—but stayed on the field. “If it gets too hot for you, shut your eyes, my boys,” shouted Major Gustav Kammerling. “Empty your guns and fix bayonets!” McCook roared. And then: “Charge, my bully Dutchmen!”

The 9th Ohio surged across the field. McCook directed part of the regiment to sweep around the Confederate front line and take on the enemies in the outbuildings while he and the rest slammed into the fence directly. Muskets crossed and Bowie knives flashed in the ensuing melee.

The Ohioans held their ground. Having endured the death of a commander, and seeing their comrades fleeing back towards Zollicoffer’s Den, the Southerners broke.

Tennessee and Kentucky cavalry slowed the Union pursuit, at one point compelling the 9th Ohio to form square in the old European style. The 29th Tennessee made a stand at the cabin where the battle had begun, this time acting as a last-ditch rearguard. They ensured the safe withdrawal of hundreds of men before being forced back.

But the army's retreat was wild and disorderly nonetheless. The roadside was littered with firearms (a motley, assorted bunch of flintlocks, shotguns, and squirrel guns--equipment failure was a significant factor in the collapse of Confederate strategy and morale), blankets, coats, and haversacks full of rations. Two cannons were abandoned. The Southerners did not stop until they reached Zollicoffer’s Den in the late afternoon.

Eighteen Union cannons arrived and began to bombard the camp. After a brief conference with his officers, Crittenden decided to re-cross the Cumberland. He still had the Noble Ellis and the two flat-boats. None of the vessels could carry cannons or supply wagons—they would have to be left behind. It would take six hours for the infantry to cross.

General Thomas’s men were worn-out, disorganized, and low on ammunition. He chose to camp for the night and launch an assault at dawn. Danville-born Colonel John Marshall Harlan, commanding the 10th Kentucky Infantry, later to become a Supreme Court justice, requested the honor of the vanguard. The Federals could see the Confederate boats crossing back and forth over the river, but they couldn’t be sure if they were filled with evacuees or reinforcements.

The Union cannons focused their fire on the crowded boats. One shell crashed through the chimney of the Noble Ellis, another blew off part of the wheel, another set her ablaze. One of the flat-boat was holed and “sank rapidly.” Men and horses leapt into the Cumberland and tried to swim to safety—some drowned. Nevertheless, most of Crittenden’s army managed to cross the river.

“One of the most brilliant victories”

The next day, Thomas’s men found the earthworks empty and the camp abandoned. Union surgeons tended to a group of sick and wounded Confederates who had been left behind. Others explored the mysterious den of their enemies. John Dow, a bugler from Ohio, grabbed a “splendid double blanket,” tobacco, and a cornet. One soldier came across Zollicoffer’s tent and read letters from his daughter announcing the birth of his grandson, hoping he might be able to visit soon. He put them aside, feeling “more like weeping than rejoicing.”

The Confederates continued the retreat all the way to Knoxville, Tennessee. General Crittenden was disgraced, accused of treason, and transferred to an obscure post along with General Carroll. Both men would later be removed from command for continuing drunkenness. The army was beaten badly, but the enlisted men remained resolute and confident. A Union soldier found a note written by an anonymous Confederate: “We fought you bravely and desperately but misguidedly. We leave here under pressing circumstances, but do not feel that we are whipped.”

Mill Springs in Context

In January, 1862, the American Civil War had not yet reached fever pitch. A few battles had been fought—Bull Run and Wilson’s Creek stand out—and the Confederates had won most of them handily.

The Confederates had also massed an intimidating force in southern Kentucky, prompting William Sherman to insist that he would need 600,000 men to keep them in check.

The decisive Union victory at Mill Springs came as a welcome relief to the Northern home front and a heavy blow to Confederate plans for the border state. Their line pierced, their morale shaken, the whole force withdrew into Tennessee by the end of January.

The Federals kept up the pressure, capturing Nashville by way of the Cumberland River, and by March, the Confederate army had fallen back all the way to Corinth, Mississippi, with a bloody defeat at Shiloh on the horizon.

If these events have an air of inevitability now, they did not have one then. At Mill Springs, General George Thomas, later to become one of the brightest stars in the National pantheon, withstood a surprise attack delivered by a superior force and thoroughly defeated his opposition, setting off a chain of events that quickly secured Kentucky for the Union and dimmed Confederate hopes for the remainder of the war.

Related Battles

262

552