Hell Hath a New Name

Of all places of confinement for soldiers and civilians documented in Lonnie L. Speer’s seminal 1997 work, Portals to Hell: Military Prisons of the Civil War, one has become such a legend that in the public’s historical memory it is sometimes thought of as the only Confederate prison — or the only one in the Civil War. Camp Sumter, Anderson Station, in southwest Georgia, popularly called then and now “Andersonville,” is the subject of a painting (“Near Andersonville”) by Winslow Homer, a Pulitzer Prize-winning novel (Andersonville) and an Emmy Award-winning, George C. Scott-directed television drama (“Andersonville Trial”).

Partisan memoirs have substituted for scholarly study during most of the time since the prison closed, creating misunderstandings about its history. For example, Andersonville, contrary to myth, only opened in late February 1864. Impressed and enslaved black labor, male and female, built it, and the inmates were of many backgrounds: Union enlisted soldiers and sailors — white, black, Native American and of many nationalities — white officers who had commanded black troops and civilians captured serving the military, including at least two women. Francis Jane Scadin, taken prisoner with her sea captain husband Herbert Hunt, gave birth to the only child born at the prison. Other women accompanied their Confederate officer husbands to Andersonville, and local women did what they could to ease the massive suffering of the inmates, including a few who even helped men escape. The prison largely served as only a hospital after September 1864, when most of the prisoners were transferred to a bigger and better new facility, Camp Lawton near Millen, Ga. Andersonville finally closed in early May 1865. During those last months, barracks, a hospital building and other facilities were built for the remaining prisoners.

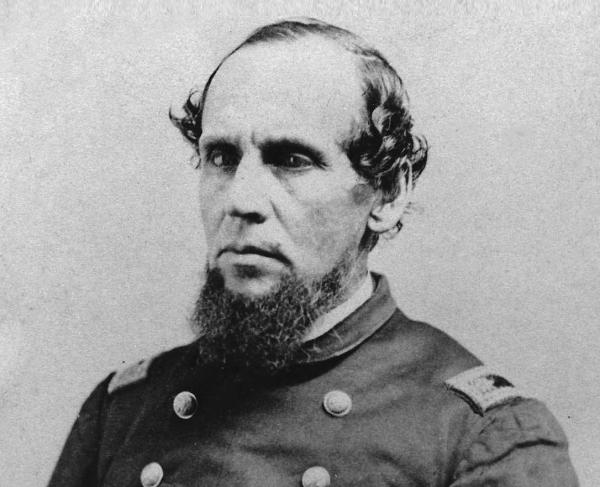

The horror of what happened at Andersonville is hard to appreciate. Some 40,000 individual prisoners entered it and 12,949 of them remain there today, almost all victims of disease made worse by malnutrition, exposure and emotional breakdown. Insects were so thick that the ground in this grassless and treeless open air pen appeared to move. Confederate civilian Ambrose Spencer testified that he smelled the prison from miles away. A lightning strike opened a spring that saved lives by providing clean drinking water. At their peak population of around 33,000 men, the confined could hardly all lie down at the same time. Conditions at Andersonville were so bad that one veteran estimated that by 1890 less than 1,000 of its survivors still lived! Some of the guards and members of the garrison died from the conditions there, although not at the same rate as the prisoners. Otherwise healthy men, including Andersonville’s second commandant, Brig. Gen. John H. Winder, who were exposed to the interior of the stockade became infected with a facial disease.

If Andersonville was the worst prison situation in the United States in American history, it was not as a result of any conspiracy. The growing numbers of prisoners of war confined in the Confederate capital of Richmond had become a serious security concern by 1863, particularly as supplies for soldiers and civilians in the city dwindled. No nation, however, has ever just released its prisoners of war. The Confederate government ordered a new prison erected far from the front lines and in a place with adequate food, water and shelter. Prison camps make unpopular neighbors, however, and location selection was difficult. Confederate officials, in desperation, rushed to completion a stockade on a site that only met two of its criteria: the inmates would be far removed from rescue and it adjoined a railroad. Only some 75 people permanently lived near the site, and their crops alone could not have sustained even the guards and garrison. The prisoner problem had only been transferred from Richmond to Deep South Georgia.

Ultimately, only about 30 inmates successfully escaped from the prison. This was despite the effort of sympathetic slaves, who sought to help the white soldiers they saw as imprisoned armies of liberation. As Sherman’s army prepared to march across Georgia, scores of inmates, often in large groups, used the opportunity to flee the prison. In some cases the initial flight was hardly more elaborate than walking away, but local militias, home guards, posses and even individuals recaptured almost all those who tried. The Confederate government eventually ringed the stockade with forts and built more walls to prevent a mass escape or rescue.

Conditions at Andersonville, combined with Confederacy-wide systems failure created the tragedy there. Even as late as 1860, the United States, as a whole, had little experience with effective, nationwide administration beyond delivering the mail. But the North’s superior resources prevented widespread or, usually, even localized suffering, despite waste, fraud and incompetence. The Confederate States of America, however, also suffered from the effects of a segmented transportation system, a lack of manufacturing facilities and a hostile captive labor force. As the war continued, railroads failed; the U.S. Navy blockaded or captured harbors; factory production declined for want of materials; and the enemy, reinforced by hundreds of thousands of the self-emancipated, male and female, as laborers and, later, as soldiers and sailors, advanced deep into the Confederate heartland. As Sherman’s army marched across Georgia in late 1864, it found supplies impressed by the Confederate government from southern farms stockpiled at railroad stations awaiting trains that never came, even as the South’s soldiers, civilians and prisoners of war starved.

Studies of systematic failure in management have specifically used Andersonville, with its confused, complicated and ineffective bureaucracy and overwhelming shortages as a model. Confederate inspectors and even officers within the prison — including its first commandant, Alexander W. Persons — pleaded for more resources and for the transfer of most of the prisoners elsewhere. Persons would later go to court to unsuccessfully try to have the prison closed as a public nuisance. Commandant Winder even pleaded unsuccessfully that at least the sickest prisoners be sent to the Federal lines and released on parole.

Andersonville needs to be remembered. Mismanagement and public passions can kill, even today. People still hold individuals, not circumstances, accountable. John McElroy, for example, wrote Andersonville: a Story of Rebel Military Prisons (1879), a best-selling collective prisoner memoir wherein he condemned everything about white Southern culture, up to and including its music. Defenders of the Confederacy up to the present day, however, have mistakenly answered that the northern prisons were no better but only less notorious than Andersonville. Regional partisanship has falsely painted the people of each side, then and since, as having some sort of culturally inherent indifference and inhumanity.

In another aspect of the Andersonville story that has echoes in the present, Swiss-born Confederate Capt. Henry Wirz, the officer responsible for taking the prisoner roll and assigning volunteers to work details, was tried by a United States Military Tribunal immediately after the war and the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. That court sentenced him to death on, at best, unproven charges. Orrin Smith Baker of Massachusetts and New York, the volunteer, unpaid attorney for Wirz, was severely limited in his defense by the panel Federal officers, all of whom were awaiting promotions.

Ironically, Wirz had forced the prisoners to point out to him for arrest those prisoners who had robbed and even murdered other inmates. The prison population, with the captain’s encouragement, then tried the “Raiders” by jury and hanged five of the worst offenders. He also released a delegation of sergeants to go to President Lincoln to successfully petition for restarting the prisoner exchange. (Bureaucratic failure, however, prevented the release until almost the end of the war, and the resulting movement of prisoners back and forth from Andersonville added to their suffering.) Wirz thus fought for justice for helpless prisoners, but he failed to receive any of the same from the United States government after the war.

When Confederate Pvt. James W. Duncan, the prison’s cook, appeared at the trial to join even some former prisoners in defending the Confederate captain, the prosecution had him immediately arrested. The government sentenced him to 15 years at hard labor on spurious charges related to his time at Andersonville, but he walked away from confinement and, in his later years, testified in pension claims on behalf of some Union Civil War veterans. None of Wirz’s various superiors, all American born, were tried. Questions of whether such tribunals serve justice or a prejudiced public’s need for vengeance continue into the present.

Abraham Lincoln, in his Second Inaugural Address, spoke of healing the nation’s Civil War wounds. The graves at Andersonville’s cemetery — originally marked by famous Civil War nurse Clara Barton, with the help of former prisoner Dorence Atwater, who had smuggled out a grave register — still sometimes seem isolated and untouched by such a message. Park rangers at Andersonville National Historic Site today must field questions from visitors who seek to assign the blame for what happened there. Seldom does anyone ask instead “What have we learned?”

More on Civil War Prisons

While certainly the most notorious, Andersonville was far from the only prisoner of war camp of the Civil War. In fact, military inmates were housed at more than 150 prisons across the nation. Among the other notable places of incarceration were Fort Pulaski, near Savannah, Ga., Elmira Prison in upstate New York and Camp Douglas in Chicago. Richmond’s Libby Prison housed Union officers, while their Confederate counterparts were held on Johnson’s Island, Ohio, on Lake Erie.

To pass the time during their incarceration, many prisoners got creative. On Johnson’s Island, inmates participated in a debating society and an acting troupe, while at Libby Prison there was a newspaper and lending library. Escape plots were also prevalent, despite the threat of recapture and punishment. In February 1864, 109 Union officers made a break for freedom from Libby Prison after digging a 60-foot tunnel under the east wall; 59 men made it safely back to Union lines.

Records indicate that some 410,000 soldiers from both sides were captured and interred in these facilities, as opposed to being quickly paroled. Of these, an estimated 56,000 died of their wounds, disease, malnutrition and other causes due to their confinement. While, in aggregate, 12 and 15.5 percent of captives died in Northern and Southern prisons, respectively, some individual sites were far more deadly. For example, at Andersonville, 29 percent of inmates perished, compared to 23 percent at Elmira. After the war, more than 4,200 dead Confederates were moved from the grounds of Camp Douglas to be reinterred in a mass grave at Oak Woods Cemetery.