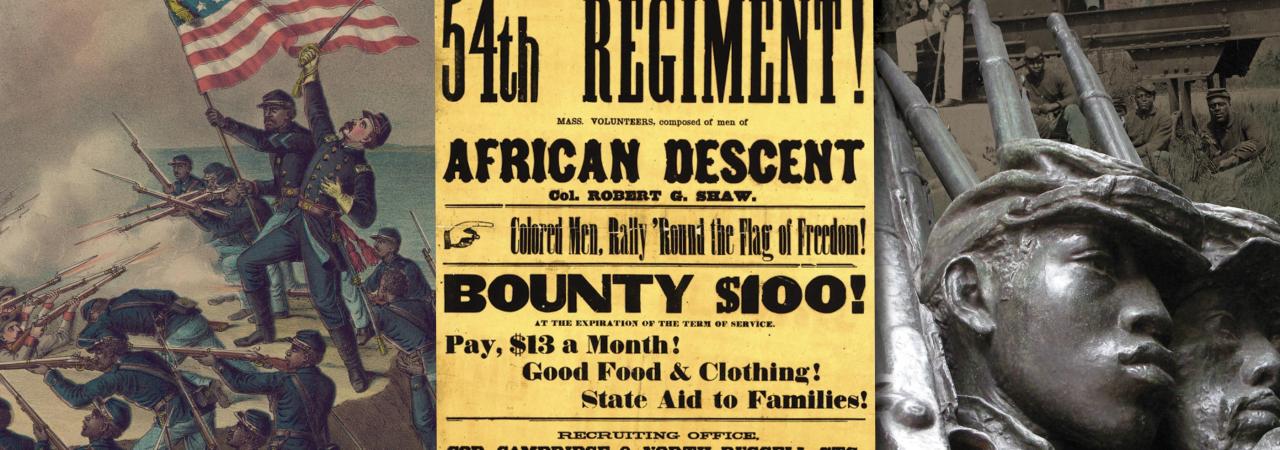

If you’ve seen the movie Glory, you probably think you know the story of the 54th Massachusetts and its gallant assault against Fort Wagner in July 1863. Hollywood and history, however, don’t always match, especially when condensing such a complicated story to two hours on the silver screen.

In its 1990 wide release (limited release on December 15, 1989), Glory ran on the big screen in 811 theaters with a star-studded cast that included Matthew Broderick, Denzel Washington, Cary Elwes, Morgan Freeman and the late Andre Braugher. Glory’s theatrical run captured critical praise, five Academy Award nominations, with three wins and nearly $27 million at the box office (or roughly $67 million today). Its continued screenings in classrooms across the country for decades has substantially influenced public understanding of the Civil War.

Weaving a sophisticated narrative that depicts the struggle Black soldiers faced during the Civil War on two fronts — against the Confederate foe and the prejudices of their own army — Glory is a crucial resource for students and audiences. Where Glory comes up short is its factual representation of the members of the 54th regiment itself. While many of the film’s characters are beloved to audiences and have been for generations, most are not the real soldiers who fought, bled and, in some cases, died during the conflict. Let’s take a look at some of the actual members of the 54th Massachusetts Infantry.

First Sergeant Robert Simmons

Born in Bermuda, Robert John Simmons previously served in the British army and worked as a clerk in the United States. Abolitionist William Wells Brown helped enlist Simmons as a private in the regiment and introduced him to Colonel Robert Gould Shaw’s father, Francis George Shaw. Each agreed on Simmons’ capabilities and soldiering qualities, and Colonel Shaw promoted him to first sergeant. Unlike Glory’s depiction of the regiment, Simmons and many of its members came from professional backgrounds and few had experienced enslavement. Estimates are difficult, but as reported on enlistments, only a quarter of the regiment was born in slave states and even a smaller portion of that number would have been enslaved.

Simmons had been born free, but that did not spare him or his family from the pain of racial violence. Five days before Simmons was wounded and captured at the Second Battle of Fort Wagner on July 18, 1863, his sister Susan Reed and her two children were targeted by a white mob in the New York City Draft Riots. Her seven-year-old son Joseph was killed by the crowd. Cited for his bravery in battle, Simmons died from his injuries in a Charleston jail in August 1863, likely without knowing the fate of his nephew.

First Sergeant Charles Douglass and Sergeant Major Lewis Douglass

Many prominent African American abolitionists involved themselves heavily in enlistment drives for the 54th. While most were too old to fight, their descendants were motivated by the same principles and aspirations. In the 54th, Sojourner Truth’s grandson James Caldwell was taken prisoner in South Carolina, Martin Robinson Delany’s son Toussaint L’Ouverture Delany fought throughout the war, and two of Frederick Douglass’ sons were among the first recruits.

Born in 1844, Charles Remond Douglass joined as a private in the 54th, but he never saw combat due to a lung condition. Spending most of his time in the regiment furloughed in New York, he was erroneously reported as having deserted in the summer of 1863. Douglass mustered out of the regiment in March 1864 after receiving a promotion to first sergeant in the 5th Massachusetts Cavalry. He was discharged from the army in September 1864.

His older brother Lewis Henry Douglass served with distinction in the 54th throughout the war. Like Glory’s fictitious John Rawlins, Shaw promoted Douglass to sergeant major, where he set the standard for the enlisted men and acted as a link between them and the officers. Douglass participated in the assault on Fort Wagner, where he was wounded. Due to the severity of his injuries, Douglass was placed on sick leave to recover in New York, and ultimately received a medical discharge in February 1864.

Drummer Miles Moore

Assigned as a drummer by Colonel Shaw, 16-year-old David Miles Moore’s role in the regiment is paralleled by the mute drummer boy in Glory. Moore served throughout the Civil War and afterward enlisted in one of six African American units authorized by Congress in 1866.

During their deployments on the frontier, Black soldiers from these units came to be known by the nickname “Buffalo soldiers.” Two of these infantry units, including Moore’s, were soon consolidated into the 25th Regiment, where he served in the regimental band until 1870.

First Lieutenant Stephen Swails

After enlisting in Elmira, New York, Stephen Atkin Swails was rapidly promoted to first sergeant. Swails and the regiment fought at Wagner, but their stories continued beyond on the shores of Morris Island. In February 1864, the 54th campaigned in Florida, executing a heroic rearguard action at Olustee that protected the retreating Union force. Here, Swails was wounded in the head, but for his exceptional bravery received a commission to second lieutenant in March. Prevented from accepting his promotion due to prejudice, it was not until January 1865 that Swails mustered into the regiment as a first lieutenant.

Following his determined efforts and the lobbying of Massachusetts Governor John Albion Andrew, Swails became one of the first African Americans to receive a promotion to combat officer’s rank. Five more Black enlisted men in the 54th and 55th Massachusetts would obtain commissions, but none would command troops in battle. After the war, Swails became an agent in the Freedmen’s Bureau, participated in South Carolina’s state constitutional convention, and was elected four times to the South Carolina Senate, where he served as president pro tempore. Despite these achievements, as with other Reconstruction governments across the South, disaffected whites in South Carolina used intimidation, violence and fraud to reassert white supremacy, push out Black voters and politicians and abolish the rights that regiments such as the 54th had sacrificed to win. Surviving two assassination attempts and unable to campaign due to threats to his life, Swails never held office in the state again.

55th Massachusetts

Governor Andrew formed the 55th Massachusetts to accommodate the swell of eager recruits for the 54th. At around 25%, the 55th included a higher proportion of formerly enslaved than its sister regiment. Deployed to Fort Wagner after the 1863 battle, the 55th participated in a two-month siege, which eventually secured its capitulation. Although sent to Florida, the regiment did not participate in the Battle of Olustee, however, the 54th and 55th both fought at the Battle of Honey Hill during the later stages of the war. At Honey Hill, the 55th suffered heavy losses while advancing under rifle and artillery fire. Andrew Jackson Smith, a self-emancipated freed man fighting in the 55th, received the Medal of Honor at Honey Hill for saving the regimental colors. In 2001, President Bill Clinton presented the award to his grandson.

Valorous conduct by regiments such as the 54th and 55th Massachusetts convinced hesitant decision-makers and the white public of the capacity and dedication of Black troops, opening the way for approximately 180,000 African Americans to serve in the Civil War. While Glory may eschew faithfulness to an accurate regimental history, its emotional power and resonant themes clearly illustrate the undeniable historical truth that Black Americans fought and died for their freedom. No film, however, can do complete justice to capture the triumphs, pains and disappointments contained in the history and stories of the men who served.

Visit the Massachusetts Historical Society website to view portraits and artifacts of several of the members of the 54th featured here and connect with their stories of service.

Related Battles

1,515

174