Few cities in the American conscience are seen as the center of the American Revolution as much as Boston, Massachusetts. Though not the only hotbed for rebellion against the British Crown, Boston is where most of the early resistance efforts began, which a large impact across all the colonies.

Founded in the 1630s, the small village which became Boston was located on a peninsula between the Charles River and Massachusetts Bay, connected by a narrow isthmus to the mainland. Established by the Puritans, Boston was home to nearly a dozen churches ranging from the Puritan Congregationalist to the Church of England. The largest was the South Meeting House with a capacity nearly 5,000 people (which was the reported attendance on December 6, 1773 for the large public meeting held before the Boston Tea Party). Like other colonies, the churches of Boston represented an integral part of daily life. Church leaders, likewise, held a similar stature to politicians in the colonies.

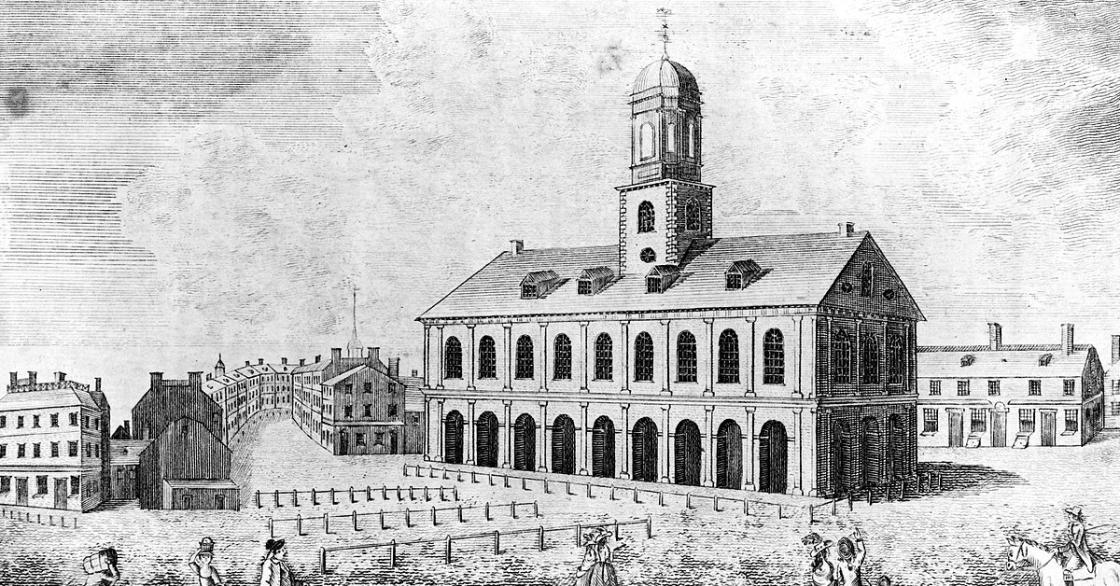

One of the traditions from early colonial days was the town meeting. This essential part of government for the New England colonies gave the colonists a sense of self government and were called frequently as a way for citizens to express concerns to their leaders, share ideas, and debate issues. Thousands would turn out to these meetings, packing large public buildings. Faneuil Hall served as the social center of the town, with the first floor serving as an open-air market and the second as a lecture hall.

Boston’s prominent religious roots bolstered its rebellious attitude. In many instances, British authorities allowed Massachusetts more home rule than their sister colonies. Though the Church of England was the official church of the British empire, it had minor influence in Boston. Because Massachusetts was not a royal colony like Virginia or others, its charter allowed for the Governor’s Council to be locally elected, not Royally appointed. This sense of self rule was important to Bostonians. They may have been loyal to their King, but they were more loyal to their home and self-determination. They did not hold the deep religious or cultural ties that many of the other colonies held with Great Britain.

Geographically, the city of Boston was located near a natural harbor with easy access to the Atlantic Ocean. The town grew quickly, relying on the shipping industry and its great access to water. These trades shaped Boston into one of the wealthiest and most populated cities in the North American colonies. By 1770, Boston’s population was near 16,000, with most being involved in trades or commerce around the shipping industry. The bustling Long Wharf, completed in 1721, extended nearly a half mile into the Boston harbor. This wharf became a hub of shipping and supporting activities. The cordage industry (rope making) constituted one of the city's a largest employers. Rope manufacturing required a large number of people and space, while shipbuilding required a lot of timber which the region around Boston was able to provide until the mid 1700’s. By the 1770’s, a lot of the lumber for shipbuilding was imported from Maine as the forests around Boston were well cleared. Boston was also a hub for the New England fishing industry, fish and lumber were sent to other colonies and also to the West Indies for molasses (which could be distilled into rum) and other rare goods.

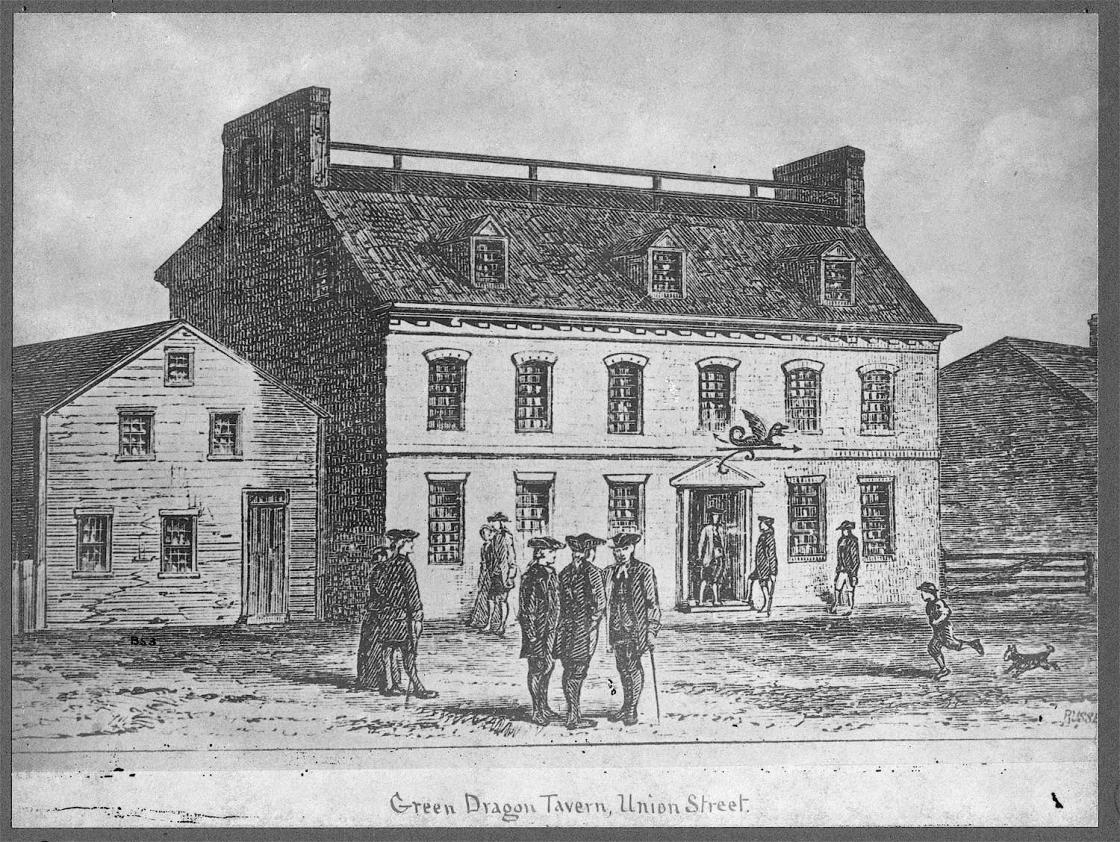

Much like other colonial cities, taverns served as the social core of Boston. Dozens of taverns served a variety of guests including both traveling clientele (transportation in the 18th century was rather limited) and the local population. Taverns provided meals, drinks, sleeping quarters, and usually some sort of public meeting space. Taverns were like modern social media pages, where you met new people and shared information from around the colonies and the globe, thanks to Boston’s port access. The average colonist consumed about three and a half gallons of alcohol in a year, double the rate of Americans today. The smokey tap rooms of the city likewise served as conduits for revolution. Groups such as the Sons of Liberty used taverns as not just meeting spaces, but also places to share news and to spy on British authorities.

Leisure time in the 1700’s was limited, most people worked throughout the day in various chores when not working in their profession. Dancing and music were an important part of leisure life for everyone, no matter the social status. If one could not afford a large ballroom in their home, most taverns hosted dances. In many ways, these social events were a great way for someone to find a future mate. Most people also enjoyed the theater, with elites attending professional theater houses. But theatrical performances were hosted outside in makeshift stages where more people could attend, not dependent on their social status. Finally, for many, small chores served as leisure activities. Sewing, gardening, reading, or spending time with friends were basic ways that colonial Americans spent their free time.

The Massachusetts State House (known today as the Old State House) served as the political center of the town and New England. Built in 1713, the state house is situated in the center of town and was shared by many agencies of the colonial government, Royal Governor, and colonial courts. Portions also served as warehouse space for merchants. It was in front of the State House on March 5, 1770, where the Boston Massacre took place, causing high tension in the town between colonial and Royal leaders.

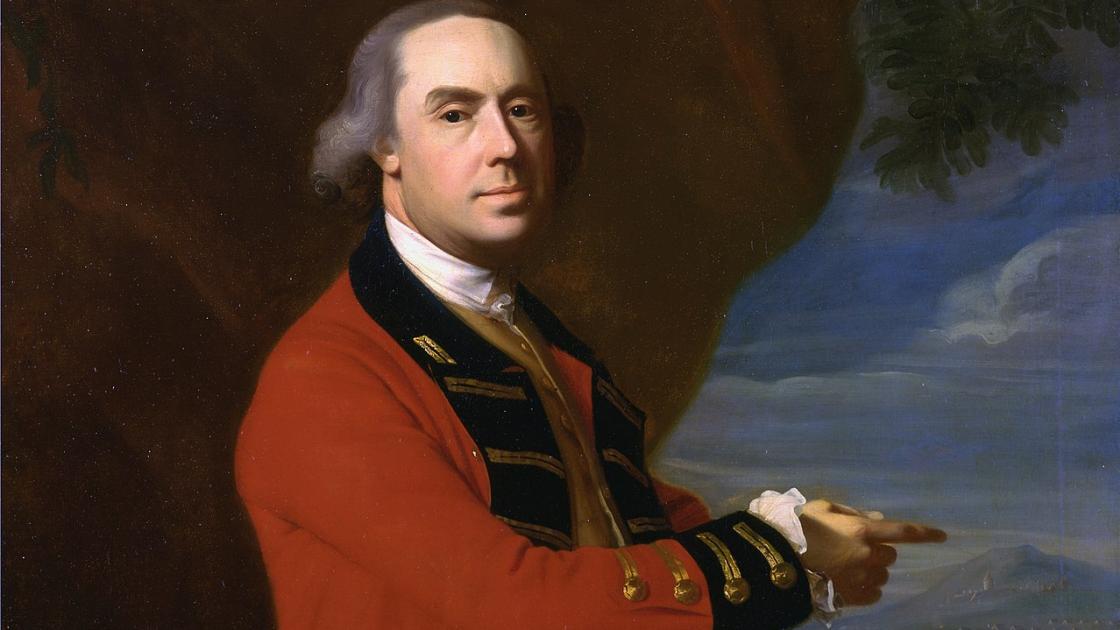

Though not the manicured park it is today, the Boston Common served as vital open space for the town. The common, a feature of many New England towns, served as an outdoor gathering point as well as grazing places for livestock. Public executions also took place on the Common. In 1774 when Major General Thomas Gage was sent to Boston with British Regulars, the Boston Common served as a camp area for the infantry.

Boston produced some of America’s first prominent leaders. Best known are John and Abigail Adams. Though technically from the outskirts of Boston, the couple were ingrained in Boston society. John was an active lawyer and, though hesitant to serve as a politician, became one of the leading Whigs in the colonies. He was known for his deliberate view of the law. John Adams’ second cousin Samuel Adams was a firebrand and in many ways the voice of the revolution. Samuel dabbled in various merchant positions, but none were overly successful. His passion was politics, and he was an inspiring orator and crafty politician. Unlike his cousin John, Samuel seemed to enjoy rocking the establishment of the British order. If he was the orator of the revolution, then John Hancock was its financier. Hancock was one of the richest men in the colonies, inheriting a good fortune from his uncle. John himself was a successful businessman, making most of his money from the shipping industry. British enforcement of shipping laws began to impact Hancock’s business, and he soon became a protégé of Samuel Adams. The two men led the Whigs in Boston along with other prominent leaders such as Dr. Joseph Warren, Paul Revere, and James Otis.

Though established across the Charles River in Cambridge, Harvard College by the mid 1700s was a leading education institution in the colonies. Established in 1636, Harvard originally educated mostly Puritan ministers. But soon, many of Boston’s business and political leaders were graduates of Harvard. Unlike most colonies where leaders attended college in England, many of Boston’s leaders received their higher education at home. This furthered their lack of dependence and connection to Great Britain.

The vast majority of Boston’s 16,000 residents were white, with a small population of free Blacks (estimated around 800 total). Slavery in Massachusetts remained legal until officially outlawed in 1783, but the institution was slowly fading and few enslaved individuals remained in Boston by the mid 1770s. The 1760 census identified 1,676 households and 2,069 family units. Historian J.L. Bell notes that Boston was a town and not a city. Though the third largest “city” in the colonies, it was still technically a town.

By the 1770s, Boston began to lose its prominence as an economic and social power to New York and Philadelphia. Those cities were expanding exponentially as Boston’s growth slowed. This led to a strain on Boston’s economy, and unemployment rose as a result. The economic conditions leading into the 1770s created a perfect storm for civil strife. Things grew worse with the taxation of tea and, more importantly, the British crack down on smuggling. Some of Boston’s richest men (John Hancock being one) made a good fortune from smuggling in and out of Boston, to which the British turned a blind eye. Simultaneously, British authorities began to enforce long standing laws on imports from the West Indies, a major source of Boston’s shipping profits.

Due to the Boston Tea Party in December 1773, Parliament passed the Coercive Acts which among other things closed the port of Boston. The local economy, already strained, began to collapse. This political step ultimately produced greater local support to the Whigs in Boston who argued against British policies, which ignited the push for independence. The radical influences of Boston and Massachusetts set the example for the rest of the colonies as events unfolded in the 1770s.