1920s postcard image of the Sentry Box, Fredericksburg, Va.

The property that George Weedon and Hugh Mercer — brothers-in-arms and, later, brothers-in-law — purchased on what is now Caroline Street in Fredericksburg, Virginia, in 1764 was well positioned, within sight of the Rappahannock River and George Washington’s childhood home at Ferry Farm beyond. The stately home that Weedon built there, known as the “Sentry Box,” remains a powerful connection to both Patriots’ legacies.

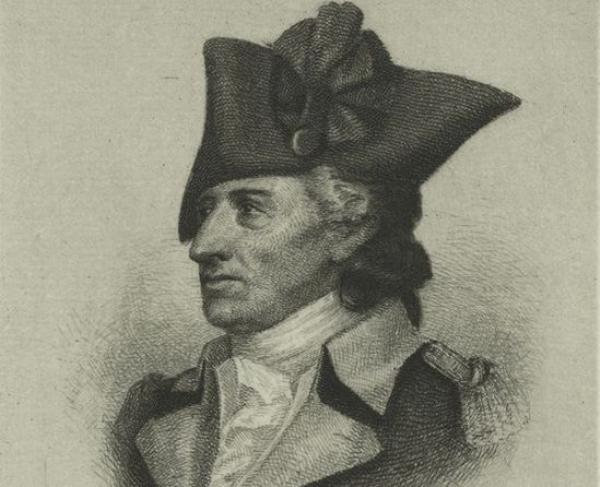

Weedon, born on his family’s plantation in Virginia’s Northern Neck, and Mercer, a Scottish-born surgeon who had served the Jacobite cause at Culloden, became friends while fighting alongside Washington in the French and Indian War. Upon the conflict’s conclusion, both men sought new beginnings and, likely encouraged by the future president, settled in Fredericksburg. Weedon married Catherine Gordon and took over management of her family’s tavern, while Mercer married her sister Isabella and began a medical practice.

But discontent in the colonies continued to mount and, at the outset of the Revolutionary War, both men took up arms for the Patriot cause, serving with the Third Virginia Regiment — Mercer as colonel and Weedon as lieutenant colonel. Following the summer of 1776, when the unit played an instrumental role in protecting Virginia from attacks led by Lord Dunmore, they moved north, joining with George Washington’s main force in New York by September. Both men aided in the campaign for New York City before participating in what historians now call the “Ten Crucial Days.” But while Weedon was tasked with bringing prisoners of war to Philadelphia following the first Battle of Trenton, Mercer continued fighting, meeting his end at the Battle of Princeton. Weedon went on to become a brigadier general, commanding troops at the Battles of Brandywine, Germantown and, later, Yorktown.

When George Weedon returned to Fredericksburg, he kept on as a tavern keeper but didn’t limit himself in the world beyond — he served as a councilman from 1782 to 1787, was president of the Virginia state chapter the Society of the Cincinnati from 1784 to 1792 and acted as mayor of Fredericksburg in 1785. An ambitious man, it is no surprise that Weedon desired to build a home that reflected his success.

George Weedon was born in Westmoreland County, Virginia, to George and Sarah Weedon in late 1734. Weedon spent most of his early life on his family’s...

Hugh Mercer was born in 1726 to Ann Monro and William Mercer, a Presbyterian Minister, near Aberdeenshire, Scotland. He earned his doctorate in...

Weedon’s ledgers and personal records, covering the period of 1734–1793, convey that he presided over the construction of the two-story, wood-framed home. Between construction and materials, these records indicate that the original home cost approximately $2,185. While George and Catherine were childless, the home was full — thanks to the presence of sister Isabella and the five Mercer children. The close quarters predicament even prompted an expansion of the home.

While built in the Federal style, the structure that passersby see today is the product of 230-plus years of additions and alterations that drew from Georgian, Greek Revival and Colonial Revival architecture. The original home was also flanked by numerous one-story buildings, consisting of a kitchen, a meat house, a study and an icehouse, which has a unique Civil War connection.

When General Weedon passed in 1793, the home went to his wife, and then after into the hands of his nephews John and Hugh Tennent Weedon Mercer — Weedon having provided for his nieces and nephews, children of his dearest friend, as if they were his. Future generations also came to know the house; Hugh Weedon Mercer, a future Confederate brigadier general named in honor of his grandfather, was born at the Sentry Box in 1808.

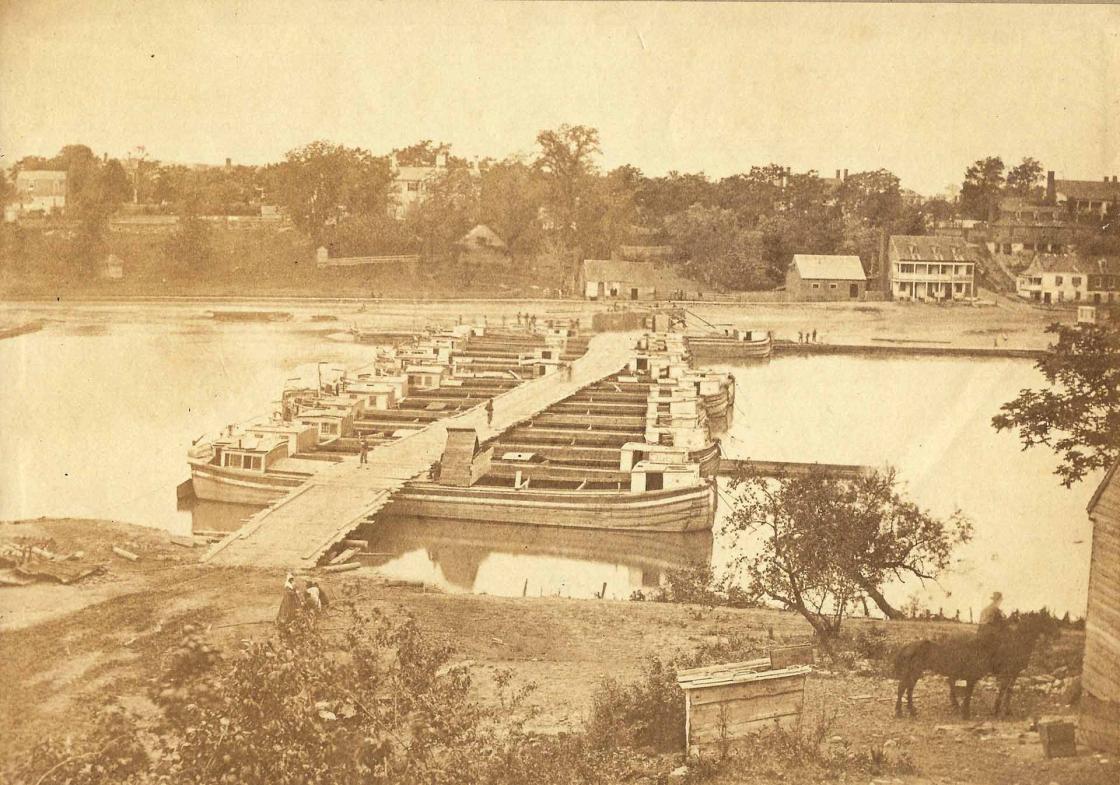

The war had made its way to Fredericksburg by late 1862, and the Sentry Box stood as witness to much of the fighting that unfurled in the streets. It also overlooked the middle pontoon bridge that Union forces used in the process of crossing the Rappahannock River — all while being fired at by Confederates on the opposite bank, where a few Southern soldiers positioned themselves between the Weedon home and the river in the Sentry Box’s icehouse.

When the Federals finished their crossing, they took to occupying lower Fredericksburg in the evening hours of December 11. While looting the homes in the city, the Sentry Box on Caroline Street was also targeted. Legend claims that an existing friendship between invading Union Brig. Gen. Ambrose Burnside and Confederate Capt. Roy Mason was the factor that spared the home.

The Sentry Box was not fully without its battle scars, as Union artillery fire had rained down on the home. Its detached kitchen was completely devastated and had to be rebuilt after the war. But the structure was not the only thing harmed upon the property during the fighting — Confederate Capt. Roy Mason, whose grandmother had bought the home in 1859, reported that he found several fallen blue-clad soldiers on the grounds.

Many layers of mesmerizing American history are tied to the property, imbuing in those who pass by or walk its halls the weight of its historic value. Its current owner has especially appreciated the presence of the past.

"I bought General Weedon's home in 1962 and, since then, my wife Mary Wynn Richmond and I have devoted ourselves to restoring the property to reflect its vast and fascinating history," said Sentry Box owner, Central Virginia Battlefields Trust board member and collateral descendent of Weedon, Charles McDaniel. "Throughout this time, we've gleaned a great deal about George Weedon and the memories he and his family made within this home. I often think about how the general carried down stories of the Revolution, even celebrating Washington's 1776 victory at Trenton with a party each Christmas. Over the past 60 years in the Sentry Box, we've filled the home with many memories of our own while paying tribute to those who came before us."

In 1992, the Sentry Box was added to the National Register of Historic Places. Furthermore, the Virginia Department of Historic Resources placed a historical marker along Caroline Street in 2008, inviting the curious minded public to glean its story.

Other Glimpses of Revolutionary War Fredericksburg

Use this interactive map to explore some additional history in the vicinity of the Sentry Box (#1 on the map below).

Hugh Mercer Apothecary Shop

1020 Caroline Street

Fredericksburg, VA 22401

From leeches and lancets to crab claws and snakeroots, this 1772 apothecary serves as a museum of medicine, pharmacy and military and political affairs.

George Washington’s Ferry Farm

268 Kings Highway

Fredericksburg, VA 22405

See where young George Washington spent his formative years through guided house tours and exhibits.

The Rising Sun Tavern

1304 Caroline Street

Fredericksburg, VA 22401

Built by George Washington’s brother, Charles, this tavern originally served as Charles’s private residence. Once sold outside the Washington family, the building was leased out as a tavern in 1792.

Kenmore Plantation and Gardens

1201 Washington Avenue

Fredericksburg, VA 22401

Explore the Georgian-style brick mansion built by George Washington’s sister, Betty Washington Lewis, and her husband, Fredericksburg merchant Fielding Lewis.

James Monroe Museum

908 Charles Street

Fredericksburg, VA 22401

Dedicated to the life of the country’s fifth president, the James Monroe Museum offers materials and exhibits on the study, interpretation and presentation of this founder.

Fredericksburg Old Masonic Cemetery

Corner of George & Charles Streets

Fredericksburg, VA 22401

Maintained by the Fredericksburg Masonic Lodge, where George Washington became a Mason, this cemetery has more than 200 graves of Masons that range from the Revolutionary War, the War of 1812 and beyond.