Bladensburg: Before the British Could Torch the Capital of the United States...

Bladensburg, Maryland, was essentially deserted. Most of its inhabitants were long gone; fleeing ahead of the British troops rumored to be marching north from the small fishing village of Benedict. Unsure of where exactly its enemy would strike, the American army under Brigadier General William H. Winder had been both advancing and retreating for the last several days, exhausting itself in the search for the invaders. A political appointee, Winder had begun to show the strains of top command, second-guessing himself and, ultimately, becoming too flustered to be an effective commander. The fact that President James Madison, Secretary of War John Armstrong and Secretary of State James Monroe all countermanded the general’s instructions only added to his frustrations.

By dawn on August 24, 1814, it had become clear that Bladensburg was the British target, and Winder’s dead-tired army was forced to march at full speed to get there first. Of the more than 6,500 troops at the general’s disposal, most were militia units from the District of Columbia, Maryland and Virginia, augmented by a small number of regular forces from the army, navy and marines. Although the Americans outnumbered the British, they were mostly raw and untested compared to the battle-hardened redcoats.

By contrast, British Major General Robert Ross commanded a force of nearly 4,500 troops, the bulk of them veterans, dubbed “Wellington’s Invincibles.” Fresh from fighting the French in Spain and helping depose Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte, these battle-hardened soldiers were now in the United States to make “Cousin Jonathan” — a pejorative term used by the British to describe their symbolic relationship to the American nation — pay for starting this little war. The Irish-born Ross, himself a veteran of many battles, had repeatedly distinguished himself under fire; the Duke of Wellington had personally chosen him to lead this expeditionary force. His immediate subordinate was Rear Admiral George Cockburn, who was no stranger to the region.

Since early 1813, Cockburn had been terrorizing the Chesapeake Bay region. Some of his more infamous endeavors included the burning of Frenchtown and the sacking of Havre de Grace, Md. He even made a feint up the Potomac toward Washington in mid-July 1813. There, the American militia turned out for an attack that never came and returned to the capital celebrating as if they had won a tremendous victory. After wintering in Bermuda, however, Cockburn returned by February 1814, determined to strike at Washington. From his base on Tangier Island in Virginia, the British admiral renewed his campaign of raids with a vengeance.

Amid these incursions, hundreds of enslaved African Americans freed themselves from nearby plantations and sought refuge with the British. Nearly 200 such men took up arms against their former masters by joining the newly formed Corps of Colonial Marines. Although initially wary of the nontraditional recruits’ abilities, Cockburn soon became confident they “will neither shew want of zeal or courage when employed by us in attacking their old masters.” Not only were they gallant under fire, but their presence on the battlefield had an astonishing psychological impact on the Americans, which would be clearly demonstrated in the coming battle.

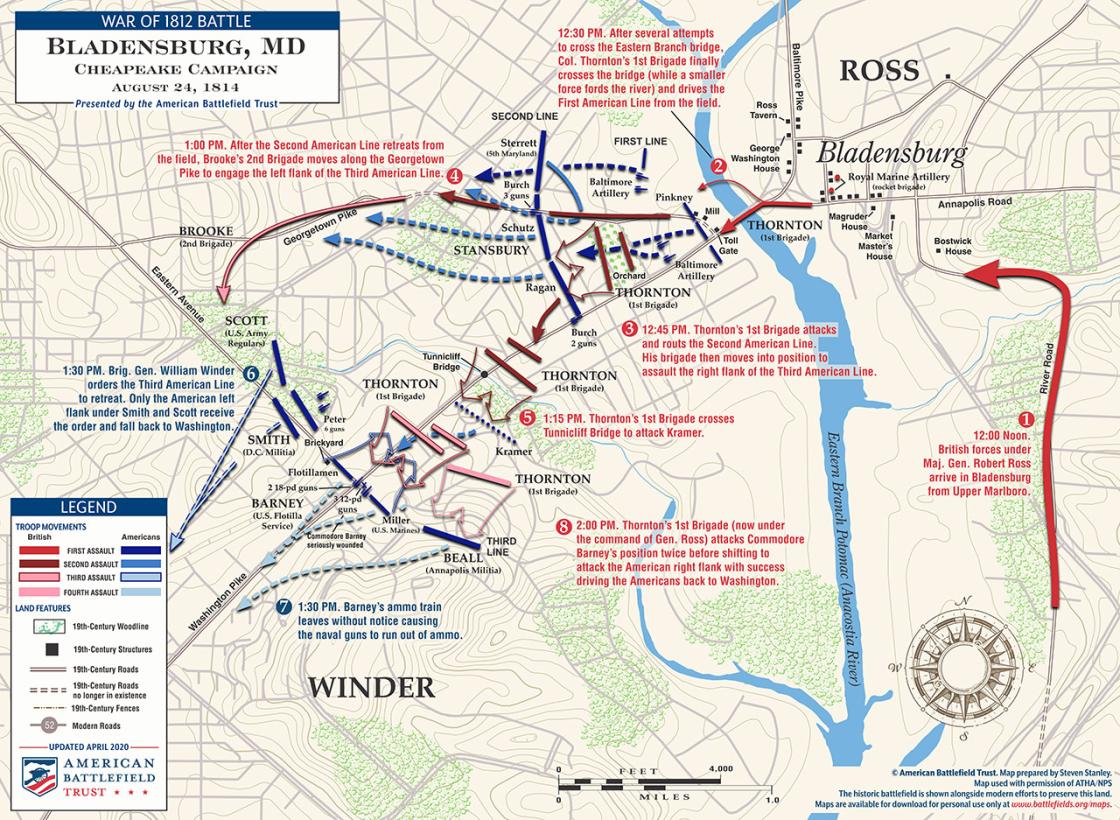

On August 24, the Americans arrived on the field first and began taking up positions just to the west of town facing the Eastern Branch of the Potomac River — today more commonly known as the Anacostia — which was spanned by a small wooden bridge leading into Bladensburg. As midday drew nearer, the heat increased dramatically, putting the soldiers at serious risk for heatstroke. As his forces arrived piecemeal, Winder organized his army into three battle lines in a triangular formation along what Ross would later describe as “very commanding heights.” Artillery in the first American line was focused on the town and bridge. Secretary of State James Monroe himself placed a second line about 500 yards behind this, a distance that would prove to be too great to offer meaningful support. Commodore Joshua Barney, late of the Chesapeake Flotilla, commanded sailors and marines in the third line some distance behind.

President James Madison arrived on the battlefield around noon to confer with Winder. Mistakenly believing the general to be in town, he and his small party were about to cross the bridge before being informed that the British had just taken Bladensburg. The presidential party quickly retired behind the first line, at roughly the same time that Major General Ross began surveying the American defenses.

From his position, the British commander could plainly see the first line’s artillery concentrated on the bridge and town, but also that the bulk of his enemy’s forces were still arriving and being placed into line. Assessing the troops that were in line, Ross realized they were too far apart — poor troop placement meant they could not support each other. Several subordinates pushed for an attack right away, while others cautioned against it until the whole force was up and ready. In weighing his options, Ross was convinced by Cockburn that the militia would pose no threat and ordered an immediate attack, despite only having a portion of his force ready. At about 12:30 p.m., Colonel William Thornton’s Light Brigade stepped off to lead the British assault; the remaining two brigades were still several miles away.

Thornton’s veteran light infantry, soldiers specially trained in rapid movement, advanced toward the bridge in good order, a sight that both impressed and intimidated the Americans. Nevertheless, when the Baltimore Artillery opened up with its six-pound guns, killing several men outright and mangling the limbs of others, the remaining redcoats took cover wherever they can find it. American artillery kept the British pinned until Colonel Thornton rode up and, brandishing his sword, urged his men forward. “You see the enemy; you know how to serve them!” he shouted as he spurred his horse across the bridge. Despite a hail of artillery and small arms fire, the British attack was renewed with newfound vigor. Watching from his position in town, Ross instructed a subordinate to get the remaining two brigades into action posthaste. Both he and Admiral Cockburn were delighted by this early phase.

Thornton’s assault was supported by salvos of Congreve rockets. These were wildly inaccurate and could terrify troops with their horrific screeching; but they were simple to launch and, in the absence of any real artillery, had to do. As these hissing rockets blazed over the American frontline — and President Madison’s position — Winder implored his commander in chief to take up a safer position. The president decided that it “would now be proper” for his party “to retire to the rear, leaving the military movement to military men.”

Despite the initial effectiveness of its artillery, the first American line panicked as the Light Brigade continued forward through the carnage. A Maryland militiaman noted that the British “moved like clock-work: the instant a part of a platoon was cut down it was filled up by the men in the rear without the least noise and confusion whatever.” With redcoats now streaming across the bridge or fording the Eastern Branch in full force, American skirmishers and artillery crews began to panic and fall back; Winder’s first line had collapsed.

Due to poor troop placement, however, the American commander had no idea what was happening on his front. It was only as militiamen began streaming toward him that Winder realized his predicament and ordered several regiments forward to restore his devastated front line. Despite some well-aimed volleys at the Light Brigade, another round of Congreve rockets caused these men to break and run as well. They did eventually rally and resume the fight for a time, but the sight of British reinforcements — including Colonel Arthur Brooke’s Second Brigade — crossing the bridge caused these militia regiments to once again break. Soon after, pressed on both flanks, the remainder of the American second line collapsed. Winder, his army crumbling around him, ordered a retreat.

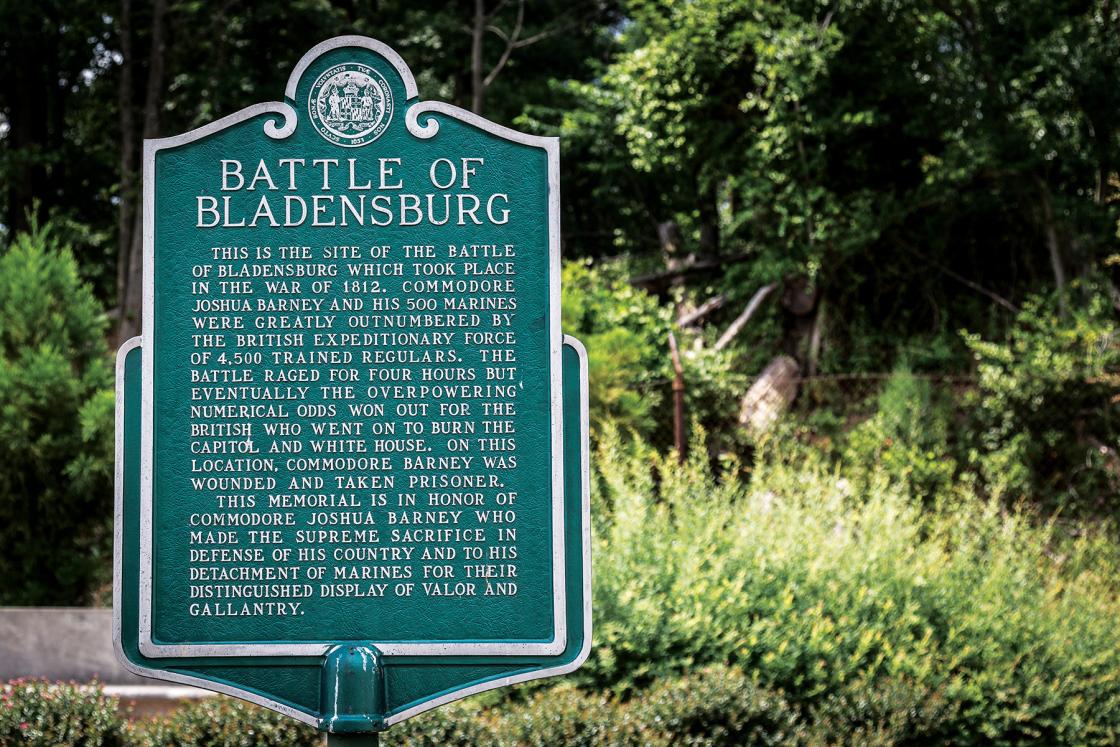

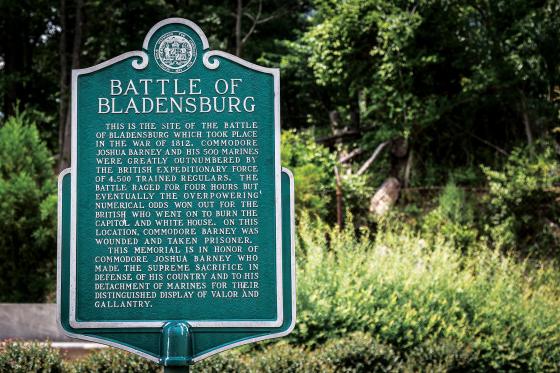

Meanwhile, Commodore Joshua Barney, in command of the third American line, waited, unaware of the general’s order. Sailors from his recently scuttled Chesapeake Flotilla and marines from the Washington Navy Yard occupied a position on the high ground, manning two 18-pound guns and three 12-pounders. Supporting them on the left was Major George Peter’s Georgetown Artillery with their six six-pound guns. Also protecting the artillery were militia units from Maryland and the District of Columbia, as well as 300 regular infantrymen. Seeing the American army below them routed, they knew a British attack was imminent. When the redcoats arrived, they approach Barney’s position cautiously, wary of the large guns protecting the road. Only when the British were within a few hundred yards of his line did the commodore order one of the 18-pounders to fire grapeshot, cutting a wide swath in the lines of the advancing redcoats. Two more assaults were attempted and likewise bloodily repulsed, with Commodore Barney noting how “all were destroyed.”

Colonel Thornton decided that a new tactic was in order. Between Barney’s heavy artillery and Major Peter’s six-pounders, the British were being cut to pieces in a deadly crossfire. Skirting around the bottom of a ravine, he personally led a charge up the hill on the American right. Marines and flotillamen charged into the British line as the 18-pounders poured grapeshot into the British flank. It was at this point that Thornton was grievously wounded — shot in the thigh by a musket ball. The British advance faltered, and the Americans pushed them back several hundred yards. Ross and Cockburn arrived on scene and took stock of a situation that had turned suddenly grim for the British. General Ross personally took command of the Light Brigade, while Admiral Cockburn ordered rocket fire on Barney’s position. Although spirited, the sailors and marines could not sustain the attack in the face of an entire brigade.

Despite his horse being hit by grapeshot, Ross led a renewed charge against Barney’s right flank. Maryland militia awaited the advance, but also broke and ran in the face of the counterattack. Simultaneously on the left flank, the District militia and U.S. regulars were informed of Winder’s order to retreat and, covered by the Georgetown Artillery, withdrew from the field in good order. The commanding general never informed Barney of the retreat, leaving the sailors and marines to fend for themselves. Enraged and disgusted that “not a single vestige of the American Army remained,” the commodore continued the fight. Gradually, his position was enveloped, and the guns were spiked after the artillery ran out of ammunition. Shot through the thigh, Barney managed to order his men to retreat before passing out due to blood loss.

Struck by the gallantry and courage of Barney and his men, Ross and Cockburn were magnanimous in victory. “They have given us the only fighting we have had,” remarked the British admiral. Barney was immediately paroled by his captors and taken to Bladensburg to have his wounds tended . Despite being severely outnumbered, the commodore’s sailors and marines had gone toe to toe against more than 1,000 British troops and inflicted heavy casualties. But it was not enough to stop the invasion.

Several hours after their victory at Bladensburg, the British formed up and pressed on to Washington City. They arrived at the outskirts near Capitol Hill around dusk, where Major General Ross sounded the call for parlay to discuss the terms for surrendering the city. As the government had fled, however, no one was left to respond to his call. Ross victoriously entered Washington to teach “Cousin Jonathan” a lesson he would not soon forget.

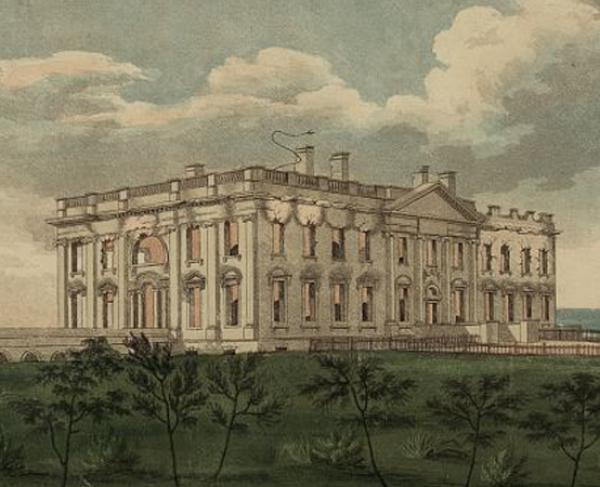

As British forces entered the American capital, they received fire from the stately Sewell House on Capitol Hill. General Ross’s horse and two corporals from the 21st Foot were killed by these assailants, members of Barney’s Chesapeake Flotilla. Ross had ordered that private property would be respected, so although the house was burned in retaliation, it the only such residence the British destroyed during the raid. The Americans had set fire to the Navy Yard themselves, but the redcoats targeted other military and government buildings, including the Capitol, the President’s House and the Treasury, as well as the State, War and Navy Department buildings. Overall, there were only a few instances of looting, and those caught were immediately punished. Following a deadly explosion at the Greenleaf Arsenal and severe storms in the city’s center, Ross and Cockburn determined that their time in Washington was at an end after just 26 hours, and began falling back to their ships. Thus ended the only foreign attack targeting America’s capital until the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001.

Related Battles

200

250