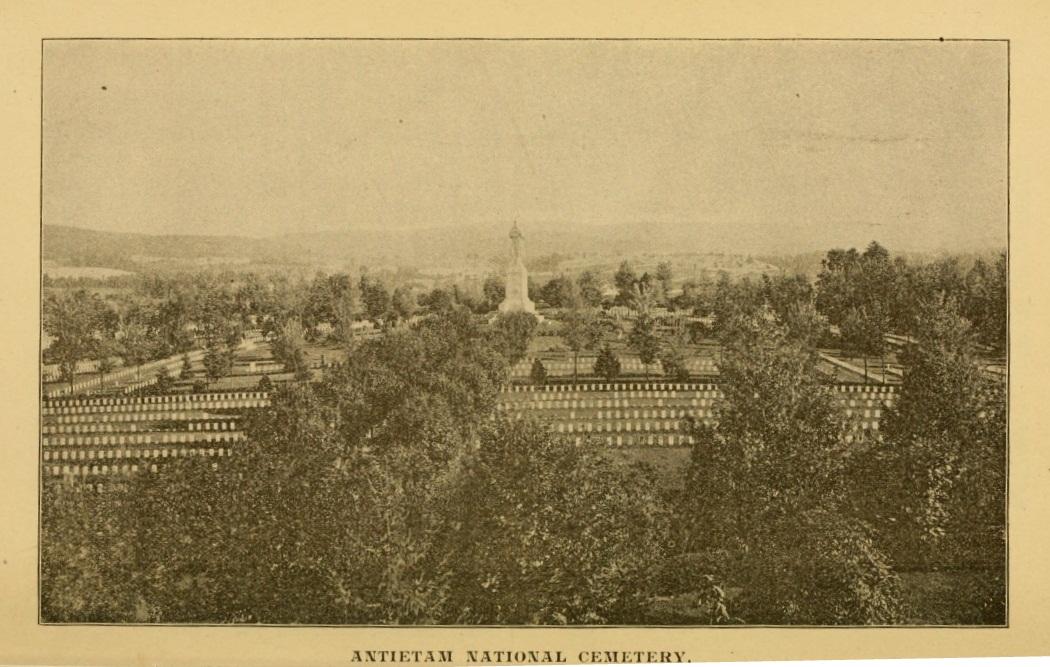

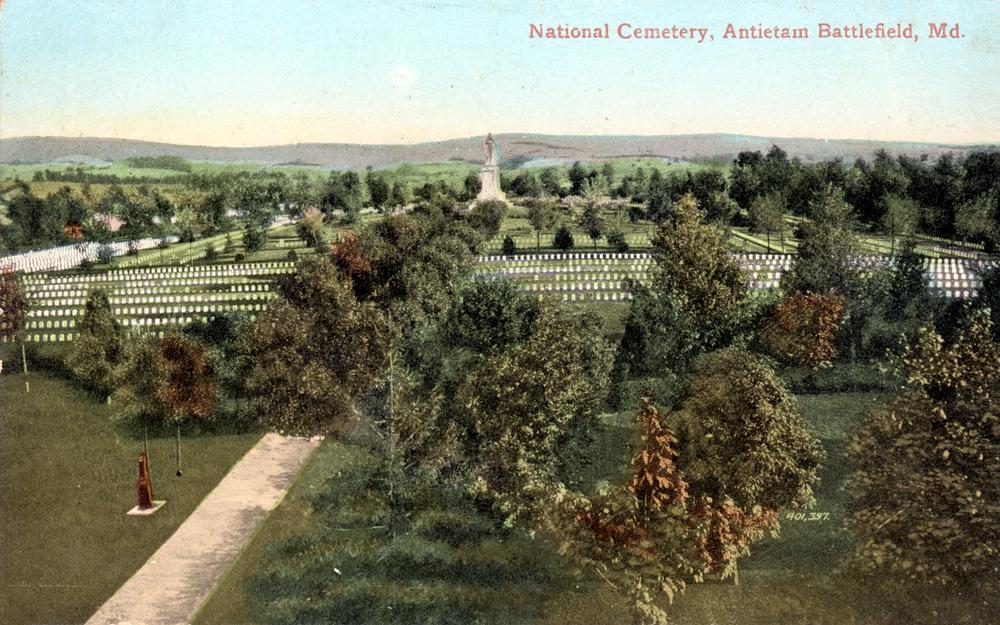

Antietam National Cemetery

The country had seen nothing like it – 3,675 Americans dead in the course of one day. Antietam lives in infamy as the bloodiest day in American history. As the firing ceased and the smoke cleared on September 17th, a question loomed over the citizens of Sharpsburg and the Antietam valley: what were they to do with the carnage wrought upon their community? Even before the armies left, Union soldiers formed burial parties to help identity and inter their comrades. These shallow graves, located on the property of farmers and citizens of Sharpsburg, were often haphazardly marked or not marked at all. William Roulette, whose farm stood near the center of the battlefield, returned to find more than 700 soldiers buried in his fields.

But as the Confederates retreated following the battle, their dead were often left where they fell. “The stench is intolerable,” one visitor to the battlefield proclaimed, “from whatever point a breath of wind proceeded a fresh effluvium assailed the senses.” Henry Kyd Douglas, an aide to General Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson, wrote that “the dead and dying lay as thick over it as harvest sheaves. The pitiable cries for water and appeals for help were much more horrible to listen to than the deadliest sounds of battle.”

Indeed, not even the Union dead received what would be considered a proper burial. As the Autumn rains began, shallow graves across the field began to again reveal the battle’s carnage. In January 1864, the Maryland General Assembly approved the purchasing of a piece of land on the battlefield “for the reception of its dead.” The Assembly appropriated $5,000 for the purchase of the land and, in March 1865, appointed a four-man committee headed by Sharpsburg physician Dr. Augustus A. Biggs. Biggs and the committee began considering possible cemetery locations, eventually settling on 11 and a half acres near the town of Sharpsburg, high ground which served as General Robert E. Lee’s observation point during the battle. From this point, visitors could view almost all major points on the battlefield.

To aid the committee, the Maryland Assembly requested financial aid from various other states to pay for the removal and relocation of existing graves throughout the battlefield. Eighteen states contributed a sum of $62,229.77, in addition to Maryland’s contribution of $16,000. The removal of remains took ten months, beginning in October 1866 and ending in August 1867. Two men, Aaron Good and Joseph Gill helped to locate and identify gravesites. They used letters, diaries, receipts, markings on belts or cartridge boxes, photographs, and interviews with relatives and comrades to identify many of the unknown dead.

Originally, the cemetery was intended to contain soldiers from both sides of the war. But, in the wake of the Confederate defeat, the financially devastated Southern states found themselves in a challenging position to contribute the necessary funds to the cemetery. This, as well as bitterness over the recently ended war, compelled the Maryland Assembly to recant their invitation.

As plans neared completion, Antietam National Cemetery drew partial inspiration from the Soldiers’ National Cemetery at Gettysburg. An initial plan to bury soldiers with no identification of regiment or state encountered protest from Northern state legislatures who insisted that their donation should guarantee their dead to be buried with fellow sons of their statehood. Thus, each state received a plot of gravesites designated so that its soldiers may rest together. The trustees allowed these plots to contain not only the dead of Antietam but also those that died at other engagements in Maryland, including the Battles of South Mountain, Crampton’s Gap, and Monocacy. By the cemetery’s dedication, the committee recorded the interment of 4,766 Civil War-era graves.

On September 17, 1867, Sharpsburg welcomed thousands for the dedication of the cemetery on the battle’s fifth anniversary. In attendance were President Andrew Johnson, four members of his cabinet, and governors of the 18 Northern states whose soldiers were interred in the cemetery. The dignitaries delivered a series of speeches in the heat of a warm September day. Some spectators wrote disgruntledly that the remarks of the dedication seemed to support the notion that Antietam National Cemetery was a common burying ground for both sides of the conflict through a theme of reconciliation with the old South.

However, the conflict exploded when some Northern governors threatened to withhold their promised contributions to the cemetery because of the controversial dedication. The trustees scrambled to find a solution or compromise to the contentious situation, even proposing that adjacent land be purchased and set aside as a Confederate cemetery. A resolution emerged, though, when Rose Hill Cemetery in Hagerstown dedicated a section for the burial of Confederate soldiers. Other cemeteries followed suit, including Elmwood Cemetery in Shepherdstown and Mount Olivet Cemetery in Frederick, where Confederates who had died in the hospitals there rested.

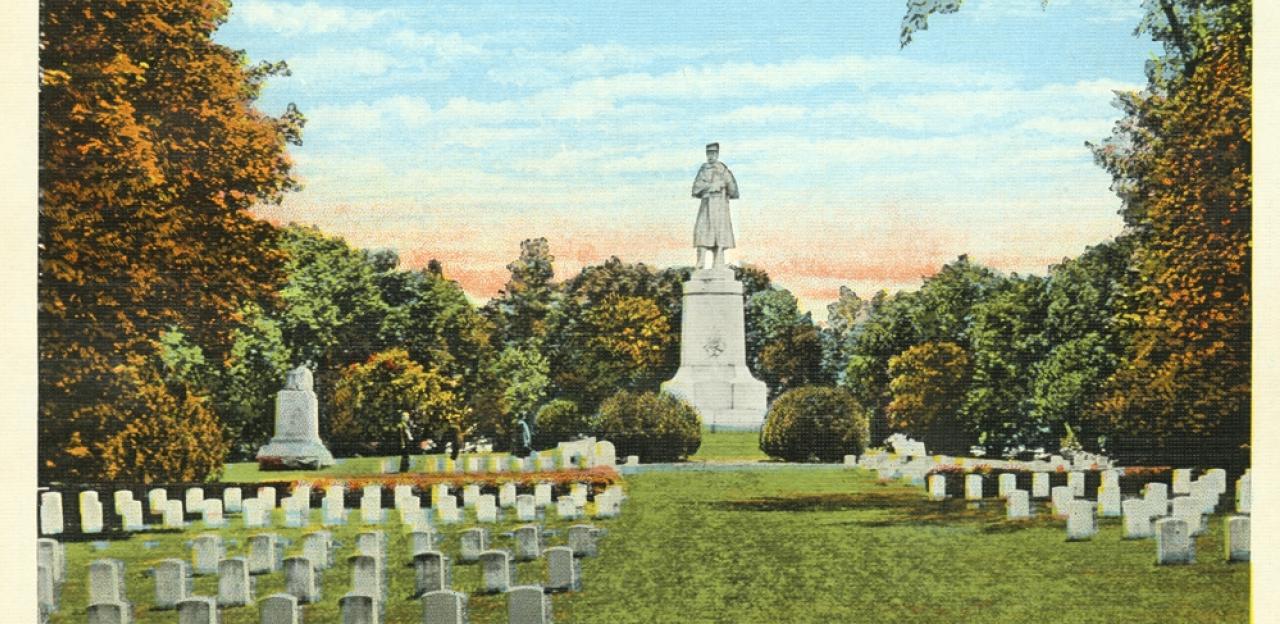

In 1880, The Private Soldier monument arrived where it stands guard over the cemetery. The monument, 44 feet tall, depicts a Union infantryman standing at rest and symbolically gazing northward to his homeland. James G. Batterson did not design the monument specifically for Antietam National Cemetery, but following its unveiling at the National Exhibition in Philadelphia in 1876, he decided on its permanent placement at Antietam. The sculpture was disassembled into twenty-seven pieces, transported up the Potomac River, and rolled up the hill on a sled of logs, where it was reassembled to stand guard over the cemetery. On September 17, 1880, the cemetery held a dedication of the statue, witnessed by both Union and Confederate veterans. Following the dedication, The Private Soldier became known among locals as “Old Simon.” To this day, the statue stands amidst the graves of so many who fell nearby “not for themselves, but for their country,” as the monument’s inscription declares.

Modern visitors to Antietam National Cemetery may find veterans from the Spanish-American War, World War I, World War II, and the Korean War buried there, while phrases of the poem “Bivouac of the Dead” mark the walking path amid the graves. And though the Cemetery effectively closed in 1953, it stands as a solemn reminder not only of America’s bloodiest day but of its honored military past.

Further Reading:

- Too Afraid to Cry: Maryland Civilians in the Antietam Campaign By: Kathleen A. Ernst

- A Field Guide to Antietam By: Carol Reardon and Tom Vossler.

Related Battles

12,401

10,316