By the summer of 1862, most Americans had resigned themselves to the reality that the Civil War would not be over as quickly as they’d hoped. As eagerness waned, the federal government issued a call for 150,000 volunteers in the summer of 1862 and threatened a draft in regions that did not fill their quota. State officials prepared to raise units with nine-month terms of service rather than three-year enlistments, and local governments offered bounties, hoping to avoid a draft through the use of these incentives. Among these nine-month recruits were the soldiers of the 130th Pennsylvania Infantry. Recruited primarily from Cumberland and York County, these fresh soldiers gathered near the state capital of Harrisburg in mid-August 1862 to begin their service. A single month later, the men who joined the 130th Pennsylvania found themselves in the middle of the bloodiest single day in American history.

In September, the regiment left camp to join the Army of the Potomac and was assigned to the Second Brigade, Third Division, Second Corps. They had their first brush with battle as they passed through the aftermath of the fighting at South Mountain on September 14, 1862, and they spent the night unknowingly resting amongst the dead. Though it was their first brush with the aftermath of battle, it paled in comparison to what came in the following days.

As the battle of Antietam began on the morning of September 17, near the now-famous Cornfield, the 130th was marching into position elsewhere, crossing Antietam Creek and moving towards the Roulette Farm. The regiment’s untested brigade was initially in the lead according to veterans but was soon placed between their division’s more experienced comrades as they pushed aside minor Confederate skirmishers. They faced a less conventional foe as well; the Roulette family had several beehives on the property. Confederate artillery had struck at least one hive, sending the bees flying into a confused rage. John Hemmingen of the regiment noted that “the little fellows resented the intrusion, and did most unceremoniously charge upon us.” Bees aside, the soldiers had more serious issues to contend with, as after they passed between the Roulette barn and through the garden, they lay down while Confederates fired from one of the many undulating crests. Edward Spangler, in a reference to their earlier insect foes, noted that now “bullets flew thicker than bees, and the shells exploded with a deafening roar. I was seized with fear far greater than that of the day before. I hugged the ploughed ground so closely that I must have buried my nose in it. I thought of home and friends, and felt that I surely would be killed, and how I didn’t want to be!”

As more of their comrades moved to the front, the regiment arose, took the crest of the hill, and began advancing towards the Confederate troops that had fortified the Sunken Road. Spangler, who previously noted his fear under fire, recalled his change in spirit. “The moment I discharged my rifle, all my previous scare was gone,” he wrote, “The excitement of the battle made me fearless and oblivious of danger; the screeching and exploding shells, whistling bullets and the awful carnage all around me were hardly noticed.” The men of the 130th, including Spangler, were now combat veterans. However, their assault was not able to storm the lane. They were stalled in the fields before it, caught under heavy fire for a considerable amount of time. Only the arrival of additional Federal troops, such as Brig. Gen. Thomas Meagher’s Irish Brigade, near the southern portion of the Sunken Road, broke the enemy line. With that portion of the fight over, the 130th was later engaged in a smaller fight off to the right of their original position. When they ran out of ammunition, with nearly every soldier having fired their own 80 allotted rounds as well as their scavenged additional cartridges, they withdrew to a reserve line at the Roulette Farm. Though combat at Antietam would yet claim many lives elsewhere on the field, the regiment’s role in their first battle was over. They spent the night near the farm that had served as the scene of their baptism by fire.

By the end of the battle, the regiment had suffered 178 casualties: 32 were killed, 14 later died of mortal wounds, and an additional 132 suffered non-fatal wounds. The regiment had approximately 650 soldiers that day, equating to a 27% casualty rate. The sheer amount of loss as a result of America’s bloodiest day was forever ingrained in the soldiers of the 130th. In addition to witnessing it as their first battle, they remained on the field, as they were among those assigned the gruesome task of the burial of the dead in the days following. Simon Whistler remembered the hot weather and “the stench from the hundreds of black, bloated, decomposed, maggoty bodies, exposed to a torrid heat for three days after the battle, was a sight truly horrid, and beggaring all power of verbal expression.” Edward Spangler similarly remembered the lane filled with the dead, citing James Hope’s well-known painting of Bloody Lane as an accurate depiction. On October 18, 1862, Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper printed a depiction of soldiers, including the 130th, burying the dead at the Sunken Road which sent the horrible image of war to the home front. At a later reunion, Whistler gestured to a spot at the Mumma Farm where they had buried “185 Confederate corpses, the one on top of the other, and indecorously covered them from sight with clay.” In total, he stated they “buried 300 Confederates, and over 100 of your own, the latter having been buried singly, each body wrapped in a blanket, and each grave marked by a head board, inscribing the name of the soldier and his command for subsequent identification.” United States soldiers buried in this way were reinterred at Antietam National Cemetery in 1866, and Confederate dead were removed to Rose Hill Cemetery in Hagerstown in the 1870s. The 130th did not finish the task of burying the fallen until September 21.

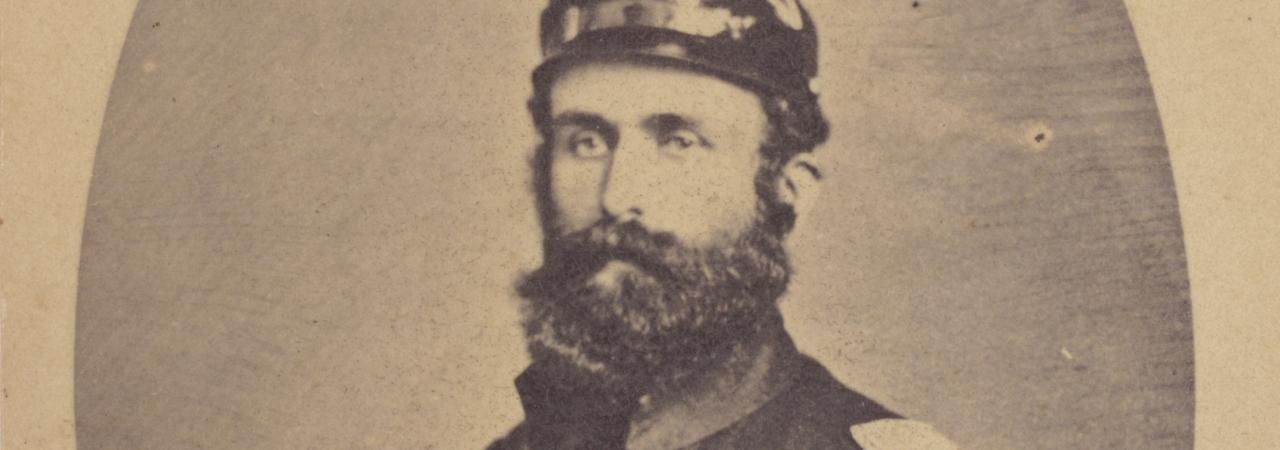

After burying the dead at Antietam, the 130th went with the rest of the Second Corps to the heights overlooking Harpers Ferry to recuperate and prepare for more campaigning. In December, the 130th’s brigade was among the first to attempt the assault on Marye’s Heights during the battle of Fredericksburg. Beloved regimental commander Col. Henry Zinn tried to rally the regiment after it stalled under immense fire, grabbing the regimental colors and crying out, “Stick to your standard, boys! The One Hundred and Thirtieth never abandons its colors; give them another volley!” Mere moments later, Zinn fell dead. They withdrew from the field in shambles.

After the relative peace of winter encampment, the 130th was engaged in the battle of Chancellorsville on May 2, 1863, in an attempt to stem the tide of “Stonewall” Jackson’s devastating flank attack. Mere days after withdrawing from Chancellorsville, the regiment’s term of service expired. They returned to Pennsylvania and were mustered out in Harrisburg on May 21. The hard-fought survivors returned to their homes, and those who returned to York were welcomed by a parade. They had served a mere nine months but witnessed three of the Army of the Potomac’s most devastating battles during their brief service.

Though their service was shorter than many of their comrades, the men who survived their time under the banner of the 130th were proud of their service. In the years and decades following the Civil War, they came together to remember. Starting in 1888, the Association of Survivors of the 130th Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers met yearly to listen to speakers and commemorate the anniversary of Antietam, the battle they felt defined their service. Sometimes, such as in 1891 when they traveled with soldiers that served in their once-untested brigade, these annual reunions occurred on the Antietam battlefield itself. Much of this event was hosted at the Roulette Farm, a natural choice due to how fundamental the property was to the regiment’s experience at Antietam. These visits allowed veterans to return to familiar fields with family and comrades, reckon with enjoyable and traumatic memories alike, and pay respects to fallen comrades buried in the Antietam National Cemetery.

In September 1904, the veterans again returned to Antietam. On the 42nd anniversary of the battle, they dedicated their regimental monument along the Sunken Lane, remembering their bloody assault on the works, their lost comrades, and the hours spent burying the dead there. Speakers told stories of their lost friends, the chaos of battle, and the aftermath of what one speaker called the “awful tornado of battle.” At the dedication, veteran John Hays delivered a poem that, in part, read:

Polished Granite, graceful gift of grateful state is here unveiled

To tell the story of when in battle’s heat this height we scaled;

That the people might forever treasure name of “Bloody Lane”,

And Pilgrims hither turn their steps as to some sacred fane;

That the generations passing down the ages here may gain

larger love of country as they learn the reason for this stone.

It marks the spot where heroes stood and fought. Not for that alone

Stands here its classic form with point directed too the sky.

Two-fold its purpose. Base upon the earth, head uplifted high,

It speaks of deathless deeds done here, and then it points to higher way….

So, before we part, in names of those who died for dearest land

Of ours, in names of those who since have died and those to go,

We take this granite shaft, and in the shining after glow,

When the night of death is near, within each breast the feeble heart

Will swell with pride at though of honor given the little part

We took so long ago, and then from weak’ning life depart.

Once again, tho’ never more some, bow down the reverent head

In Honor of our comrades, here, so nobly, numbered with the dead.

Further Reading:

- The History of the One Hundred and Thirtieth Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry By: Terrence W. Beltz.

- My Little War Experience with Historical Sketches and Memorabilia By: Edward W. Spangler.

- A Soldier’s View of Their Dedication By: John Hays, II

Related Battles

12,401

10,316

12,500

6,000

17,304

13,460