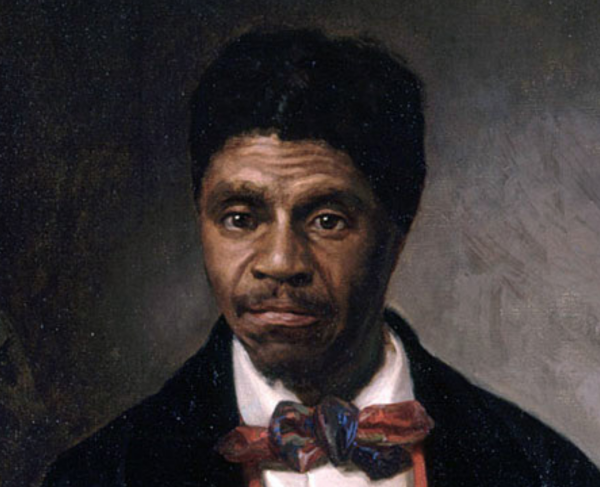

John C. Calhoun

John C. Calhoun served as one of the most influential politicians in the United States during the antebellum era, and his shifting political loyalties exemplifies the politics of many Americans which changed as the United States grew increasingly sectional.

John Caldwell Calhoun was born on March 18, 1782, on a plantation in the South Carolina backcountry. In his youth, Calhoun received a limited education, but he was intelligent and taught himself in subjects where his modest education lacked. As a result, Calhoun attended Yale University where he excelled as a student. After his graduation, Calhoun became a lawyer and soon entered politics. His marriage to his first cousin and heiress, Floride Calhoun in 1811 enabled him to become an established member of South Carolina’s planter class.

Calhoun’s transition from a proud nationalist to an unequivocal defender of states’ rights and slavery began in the mid-1810s. In 1811, South Carolinians elected Calhoun to represent them in the United States House of Representatives. At this time, Calhoun was an ardent nationalist who supported Henry Clay’s American System, an economic plan that consisted of a high protective tariff, a large national bank, and a system of federally funded internal improvements funded by high taxes. Additionally, Calhoun and John Quincy Adams were close personal friends and similar to Adams, Calhoun denounced the British for their attacks on American ships and supported the embargo that led to the War of 1812. Calhoun himself was a War Hawk and fervently supported the War of 1812. In 1817, Calhoun left his position in Congress to join President James Monroe’s cabinet as his Secretary of War. While in Monroe’s cabinet, Calhoun grew apart from Adams, which the debate surrounding Missouri in 1820 aggravated by hardening their contrasting opinions on slavery.

Former friends Adams and Calhoun were rivals in the 1824 presidential election until Calhoun dropped out and decided to run for Vice President (at this time, presidential and vice presidential candidates did not run on a ticket as they do now). Calhoun was easily elected Vice President by the Electoral College, but the presidential election and the controversy surrounding it permanently fractured Calhoun’s relationship with Adams and Clay, his former allies, which impacted Calhoun for the rest of his life. The Election of 1824 remains one of the most controversial elections in the history of the United States, and it was the first instance where the winner of the popular vote did not win the presidency. Andrew Jackson, John Quincy Adams, Henry Clay and William Crawford all ran as Democratic-Republicans, but there were different factions within the party that divided the votes. Neither candidate received enough electoral college votes to secure the victory. Thus, the House of Representatives was to vote on the top three candidates (Jackson, Adams, Crawford) to determine who would gain the presidency. On account of ill health, Crawford removed himself from the race. Jackson expected to win the House of Representatives vote as he won a plurality of the popular vote and electoral college votes. However, a “corrupt bargain” ensured that denied Jackson the presidency in 1824. As Speaker of the House, Henry Clay promised to win Adams the House vote in exchange for the position of Secretary of State in Adam’s cabinet. On February 9, 1825, the House of Representatives narrowly voted in favor of Adams over Jackson. Calhoun was outraged and furious over this “corrupt bargain” which destroyed his fragile relationship with Clay and Adams and aligned him with Jackson and his principles. Formerly a staunch nationalist, this corrupt bargain put Calhoun on the path to become the South’s most ardent defender of states’ rights.

As Vice President, and therefore President of the Senate, Calhoun undermined Adams through his entire presidency. One crucial example of this is that Calhoun appointed Adams’s political foes to the head of key Senate committees including the Foreign Relations Committee, the Finance Committee, and the Committee for Military Affairs, which pushed Jacksonian politics in the Senate. Additionally, Calhoun worked with Martin van Buren to garner support for a Jackson presidency, which they achieved in 1828. Calhoun remained on as Jackson’s Vice President; however, events in Jackson’s first term would once again alienate Calhoun from his political allies.

Calhoun was at the center of a political scandal that rocked Washington early in Jackson’s first term, often referred to as the Petticoat Affair or the Peggy Eaton Affair. Jackson’s Secretary of War and close personal friend John Eaton had newly married recent widow Peggy Timberlake before her period of mourning expired. Mrs. Eaton was the daughter of a well-known Washington Tavern owner and her first husband Mr. Timberlake died tragically at sea. Whispers about Mrs. Eaton’s unsavory past as a prostitute (most likely unfounded) and her affair with John Eaton droving her husband to suicide circled among Washington’s elite, which eventually turned into attacks on her virtue. Many cabinet members’ wives refused to associate with Mrs. Eaton and ostracized her. The ringleader of these women was none other than Floride Calhoun. Jackson became consumed with protecting Mrs. Eaton’s reputation, mainly because these attacks reminded Jackson of the attacks on his beloved wife Rachel, which he attributed to her early death. Calhoun supported his wife’s actions which caused a wedge between Jackson and Calhoun that would only grow with the Nullification Crisis, a crisis between federal and state authority.

By the time, Calhoun was a fervent states’ rights supporter and believed that state authority trumped federal authority. In the late 1820s, many southerners, but South Carolinians in particular, wanted to abolish the high tariff that Congress passed to protect northern industry, referred to as the Tariff of Abominations. This Tariff directly affected the southern economy as the tariff forced southerners to pay high taxes on goods they did not produce, and it reduced the amount of American cotton sold on the global market. Calhoun wrote an anonymously published pamphlet titled “Exposition and Protest” in December 1828 which protested the tariff and argued if Congress failed to repeal the tariff, South Carolina would secede from the Union. This issue gained new urgency in 1830 with a debate in the Senate, where South Carolina Senator Robert Hayne argued that states had the right to nullify federal laws when it infringed on their rights and since this tariff infringed on South Carolinian’s rights they did not have to submit to this unjust federal authority. Jackson supported states’ rights, but not at the expense of the Union. In fact, Jackson once said he “would rather die in the last ditch than see the union dismantled.” Calhoun refused to waver in his support for South Carolina during the Nullification Crisis and very publicly challenged Jackson’s position at a birthday dinner for President Thomas Jefferson in April 1830, which widened the wedge between Jackson and Calhoun. The rift between Jackson and Calhoun grew again when it came to light that in 1818 while Secretary of War, Calhoun recommended to President Monroe that Jackson be imprisoned for invading Florida. When Jackson asked Calhoun for an explanation, he refused to provide one but rather suggested that van Buren headed a conspiracy against Calhoun to remove him from power. While this conspiracy theory is mostly nonsense, Calhoun dug his own grave by refusing to submit to Jackson’s policies when they conflicted with his own beliefs, van Burren and Jackson grew closer, especially during the Eaton Affair, when van Buren sacrificially resigned his cabinet position thus triggering the resignations of the entire cabinet which enabled Jackson to build a new cabinet from scratch, one that would not be influenced by such petticoat matters.

Jackson and Van Buren successfully ran as a ticket in the Election of 1832 and in December 1832 Calhoun resigned as Vice President to take the Senate seat of his fellow nullifier Robert Hayne. Calhoun served in the Senate until March 1843. In April 1844 Calhoun became Secretary of State under President John Tyler, an anti-Jacksonian Democrat masquerading as a Whig. Calhoun supported the annexation of Texas because he believed expansion was vital for the maintenance of slavery. Calhoun zealously supported slavery and stated that slavery was “the greatest of all the great blessings which a kind Providence has bestowed upon our glorious region” adding that slavery was “the purest, best organization of society that has ever existed on the face of the earth.” Calhoun left his cabinet position in March 1845, a few days after President James Polk’s inauguration and returned to the Senate.

In his final years, Calhoun consistently supported slavery’s expansion and states' rights. Although officially still a Democrat, his tenure as Vice President under Jackson alienated Calhoun from the Democratic Party, who remained committed to Jacksonian principles. Likewise, Calhoun did not trust the Democrats to protect slavery and southern rights. Calhoun’s main goal in the last decade of his life was to destroy party differences in the South and unite all southerners in a singular sectional block to extort pro-slavery policies from the North.

In January 1850, Senator Henry Clay, Calhoun’s old enemy, proposed a series of laws known collectively as the Compromise of 1850 in an attempt to resolve the conflict over the Mexican Cession. On March 4, 1850, Calhoun gave a scathing speech to Congress vilifying the Compromise as reinforcing the North’s dominance over the South; however, Calhoun was too weak to speak, and thus James Mason of Virginia read the speech for him. In this speech, Calhoun threatened secession and prophesized disunion unless the North “restored to the South in substance the power she possessed before the equilibrium between the two sections was destroyed.” This speech served as Calhoun’s final action against what he perceived as invasive, unfair policies that infringed on the rights of southerners. Calhoun passed away on March 31, 1850, in Washington D.C. As a member of the “Great Triumvirate,” along with Henry Clay and Daniel Webster, Calhoun immensely impacted antebellum politics in his lifetime and after his death, his principles and beliefs thrived. The principles behind nullification served as the foundations for secession. Fire Eaters adopted Calhoun’s rhetoric and propagated it throughout the South which paved the way for secession. Calhoun’s progression from a hardened nationalist to a zealous sectionalist mirrors the progression of many secessionists in the late 1850s and early 1860s, who were largely inspired by Calhounian ideology.

Further Reading: