Napoleon's crossing of the Berezina, a 1866 painting by January Suchodolski, oil on canvas, National Museum, Poznań

Like most of us during the winter season, Civil War soldiers made light of the plummeting temperatures and falling snow to play games and engage in those sports which can only be practiced in the winter. During the war, however, these activities took on new meaning as rival armies jockeyed for terrain. Drawing from the Napoleonic Wars of the early 1800s, both armies used the winter to their advantage, transforming seasonal hobbies and real-life conditions into a practical training ground for the trials of combat. So, grab your snow shovels, bundle up, and man the ramparts of your impromptu winter quarters for this edition of Nature of History!

Napoleonic Winter

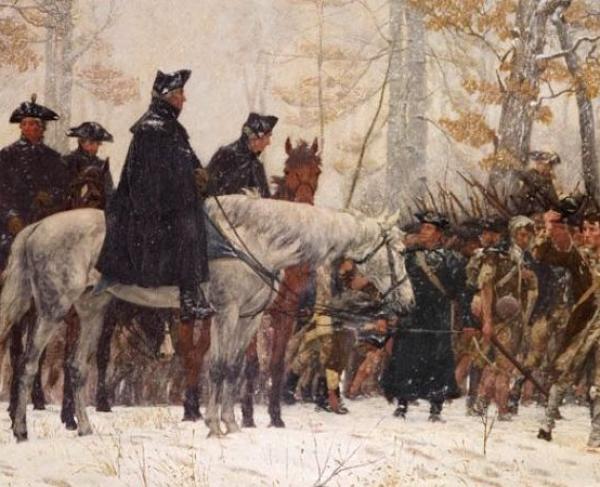

Many generals, both Union and Confederate, studied European warfare as a means of refining their techniques. Gen. George McClellan had even joined a British command during the Crimean War as an observer, learning quickly the value of fortifications and the importance of robust supply chains in a protracted, modern war. Looming large over European warfare, and by extension U.S. Army Doctrine, was the figure of Napoleon Bonaparte. From the division of armies into distinct, self-sustaining corps, to the employment of massed artillery in support of infantry, Napoleon arguably invented the style of fighting that came to characterize the American Civil War. In an eerie foreshadowing of many of the Civil Wars darkest moments, Napoleon met his defeat at the hands of supply shortages and harsh winters, the kind of which would cripple both Union and Confederate armies over the first half of the 1860s.

The school of fighting known as “Polytechnique,” which was pioneered by Napoleon, capitalized on mobile divisions of the army, each with its own cavalry, infantry and artillery components. This same form of organization was taught at West Point, with its benefits being utilized by Gen. Robert E. Lee’s Confederate Army of Northern Virginia to great effect at Chancellorsville and elsewhere. Its pitfalls were also evident, as with Napoleon’s defeat through supply constraints in Russia, as well as the overstretching of Confederate forces in the Western Theater.

In the early days of the war, undersupplied recruits under Gen. Benjamin McCulloch were caught off guard by Union forces in Missouri. At Pea Ridge in March 1862, an understrength Confederate detachment was isolated by Union forces and forced to perform a long march south through a series of running battles. This winter defeat would echo into the war, as Confederate forces were never again able to take and hold ground north of the Arkansas River.

Winter Warfare, Young and Old

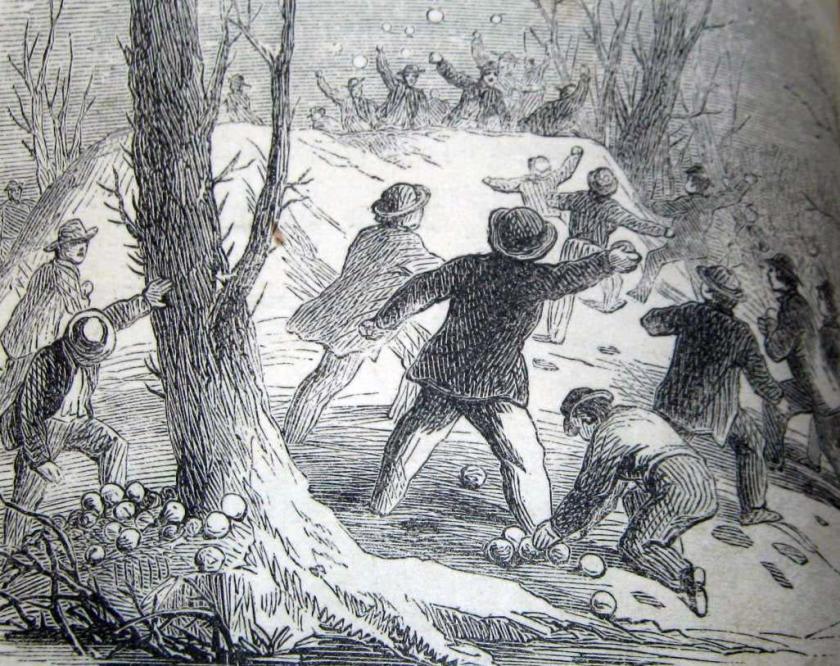

The similarity in practices between Civil War soldiers and Napoleon's forces are not limited to the level of general officers. An apocryphal tale of the Corsican Fiend’s first command came vividly to life in Civil War training. The young Napoleon, at school in a military academy in northern France, supposedly organized his classmates into two teams during a winter storm; one side built and manned a snow fortification, the other assaulted the stronghold. Bonaparte, still young, must have gathered the importance of training and drilling his men from this experience – much of his success on the battlefield came from the discipline of his men. During the Civil War, the urgent need for swift and rigorous training became apparent in the aftermath of Bull Run. It was an enormous task to turn a flood of volunteers into a fighting force that could withstand the unprecedented violence of modern conflict. This required the adaptation of activities familiar to the young, green soldiery that populated the incoming ranks.

A peculiar instance of this is an article written as part of an 1864 book, “American Boy’s Book of Sports and Games.” The text details the ways in which a number of young boys, small or large, can raise elaborate fortifications out of snow in order to protect themselves during a winter skirmish. Almost explicitly modeling the methodologies used around Petersburg at the same time to construct earthworks, the book instructs children that, “To make a snow fort, the foundations should at first be marked out, either in a square or circular form, and then clear out the snow from within, piling it upon the line of boundary to form the wall. A similar process goes on from without, and thus a good stout wall is soon produced, which must be considerably broader at the base than at the top.”

Given its tangible familiarity, usage of snow forts as a model for actual fortification would have been a widely applicable training practice. This was not far from the authors mind, as the preface of the book states, “Strength, courage, and a wholesome spirit of emulation, are among the best characteristics of all really great nations; and the presence of these noble attributes in the Man depends largely upon his training as a Boy.”

While we can now insulate ourselves from the worst weather, the lives of our 19th century forebearers were influenced by the seasons to an enormous degree. Both during the dawn of modern warfare and also its nascent steps on the North American continent, winter played an immense role in the decision making, training, and engagement of soldiers.