Civil War Icon to Marine Sanctuary

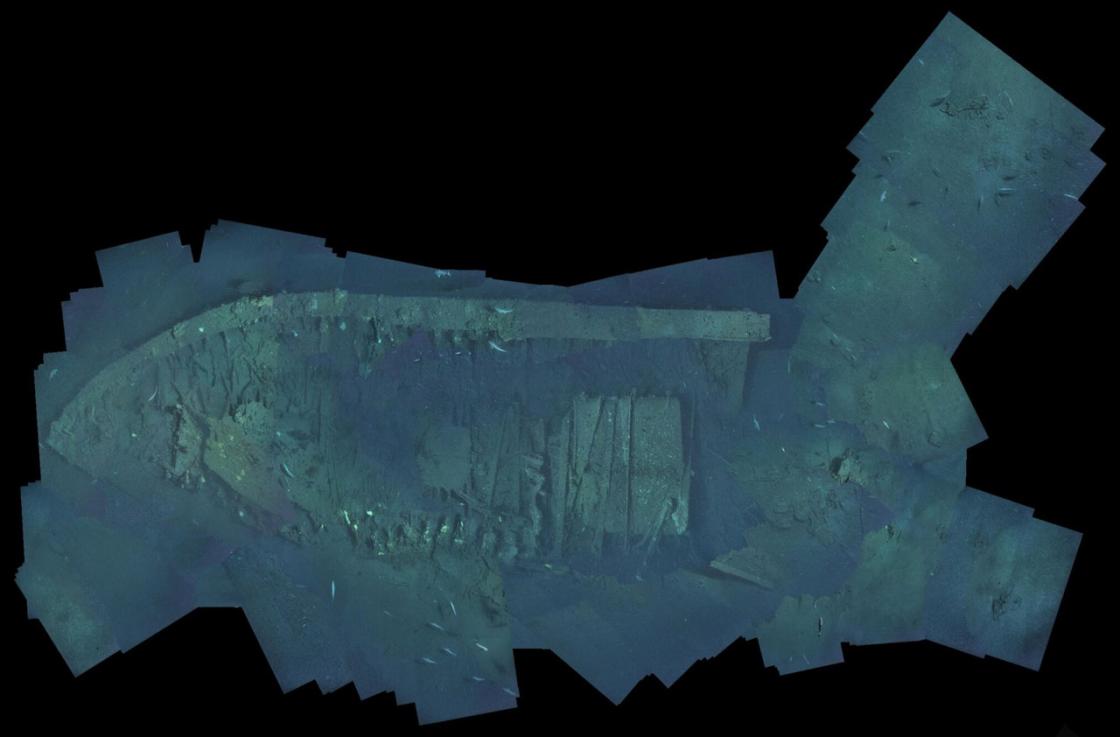

Sand tiger sharks swim alongside the wreck of USS Monitor.

Imagine diving below the waves, the few lone fish curious at your arrival become a swarm, and out of the beautiful blue-green confluence of the Gulf Stream and Labrador Current emerges a flourishing reef. Surprisingly, this ecological oasis is also a major victory in Civil War preservation.

Over a decade before the creation of the modern Civil War preservation movement, far-sighted historians, scientists, and politicians utilized a newly created environmental designation to protect the wreck of the USS Monitor, establishing the first of 16 National Marine Sanctuaries.

Saved by environmental legislation, the vessel now provides a perpetual haven for the numerous aquatic creatures that call the Monitor home. On the 162nd anniversary of the Battle of Hampton Roads, the conservation triumph revealed by Monitor’s success offers an inspiring testament to the enduring symbiosis of ecological and historical preservation.

USS Monitor and Discovery

Brainchild of Swedish-born inventor John Ericsson, the USS Monitor revolutionized naval design and gunnery. Launched in January 1862, it was the first ship of its kind to be outfitted with an independently revolving gun turret. Monitor’s first test came at Hampton Roads, Virginia, on March 9, 1862, when she battled the Confederate ironclad CSS Virginia to a draw. While Virginia demonstrated the power of iron armor against wooden warships of the Union blockade, Monitor’s ability to sustain the engagement vindicated Ericsson’s turret design.

In May of the same year, Monitor attacked Confederate defenses at Drewry's Bluff on the James River. Departing for Wilmington, North Carolina, in December, she sank in a storm off Cape Hatteras on the morning of New Year’s Eve with the loss of 16 men.

Monitor’s location remained a mystery for over a century. In August 1973, scientists aboard Duke University’s Eastward combined their geological survey of the continental shelf with a search for Ericsson’s ironclad. Of the 22 wrecks identified, only one matched the dimensions, design, and probable location of the Monitor.

Five months of analyzing blurry and baffling photographs followed. Eventually, the team realized that part of the confusion arose from the ship resting upside down. In March 1974, the team announced the discovery of Monitor’s wreck. After the determination, research vessel Alcoa Seaprobe captured images and videos later used by U.S. Naval Intelligence to produce a photomosaic confirming the wreck was indeed the Monitor.

First National Marine Sanctuary

Focus immediately shifted onto how to protect Monitor’s remains. Removed from the Navy’s official inventory in 1953, and physically located outside the jurisdiction of North Carolina’s submerged cultural resource law, federal antiquity legislation, and Coast Guard authority, the wreckwas vulnerable to private salvage.

Monitor’s salvation came from an unlikely source. In 1969, an oil spill in the Santa Barbara Channel unleashed three million gallons of petroleum, despoiling public beaches and killing untold numbers of marine wildlife. This incident, and the growing concern for protecting oceanic resources, prompted the passage of the Marine Protection, Research, and Sanctuaries Act of 1972. Included as a contested last-minute addition, Title III of the act gave the Secretary of Commerce the ability to designate National Marine Sanctuaries under the management of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to preserve or restore maritime areas “for their conservation, recreational, ecological, or esthetic values.”

Rather than create a new law to protect Monitor, Congressman Walter B. Jones, Sr., suggested using this sanctuary designation. The law, however, was untried and did not include provisions pertaining to historical, cultural, or archaeological resources. Nevertheless, in September 1974, the North Carolina Division of Archives and History nominated the site and a National Register listing for Monitor was received in October.

On January 30, 1975, exactly 113 years after the warship slid into the East River for the first time in 1862, the innovative vessel made history once more when President Gerald R. Ford designated Monitor National Marine Sanctuary (MNMS) as the first in the National Marine Sanctuary System.

While intended as tools for ecological conservation, the sanctuary protections that developed around Monitor set a precedent for the preservation of historic maritime resources.

In the mid-1990s, NOAA noticed several areas where the wreck was experiencing accelerated deterioration. In response, NOAA developed a long-term plan for conserving Monitor. Rather than raise the vessel, NOAA determined to leave the wreck in situ, augmented by expeditions to observe its condition and recover important or at-risk artifacts.

Currently, climate change presents the greatest danger to Monitor’s future. Increasing acidification and warming of the ocean may contribute to further degradation of the ironclad by damaging the wreck’s concretion (an organic layer composed of corals, sponges, and bivalves that protects the hull from salt-water) and speeding the rate of corrosive reactions. Damage from Hurricane Isabel in 2003 shows that increased storm intensity from climate change may also further disrupt the wreck.

Wildlife and Reef at Monitor

As nearly half of the world’s coral reefs have been lost due to human activity, Monitor and other artificial reefs are crucial tools for supporting and restoring marine ecosystems. In addition to possessing diverse coral populations comparable to natural reefs and providing sanctuaries for coral growth in the face of climate change, evidence suggests that artificial reefs may even sustain larger fish populations than rocky reefs, particularly for top predators.

Monitor’swreck is no exception. Its location on the northern extent of tropical fish populations extends their ranges and results in a vibrant mix of temperate and sub-tropical fish, such as greater amberjack, black and bank sea bass, scup, and grouper. Additionally, oyster toadfish, barracuda and, unfortunately, invasive lionfish live at Monitor.

Encrusting organisms around the wreck include species of coral, sponges, sea squirts, anemones, hydroids, barnacles, tube worms, oysters, and mussels. Sea urchins and brittle stars are common invertebrates, and crustaceans like crabs, snapping shrimp, and spiny lobsters can be seen scurrying around the hull.

Most awe-inspiring are some of the migratory marine species. Giant manta rays occasionally glide by divers, while some loggerhead sea turtles call Monitor their winter residence. Sand tiger sharks are also an iconic feature of the sanctuary.

Visiting Monitor

MNMS requires a free permit to dive Monitor, but these are only available to qualified technical divers due to the depth, strong currents, rapid drops in water temperature, and limited visibility.

Instead, see spectacular views of the wreck and its wildlife from your home in 360-degree 4K video on the NOAA Sanctuaries YouTube:

Fortunately, the close partnership between The Mariner’s Museum and Park at Newport News, Virginia, and the MNMS allows museum guests an immersive look into Monitor without getting soaked. In addition to the MNMS offices, the museum hosts the USS Monitor Center, and is the government’s official repositor of artifacts from the wreck. The Ironclad Revolution exhibit about Monitor and the Battle of Hampton Roads is accompanied by a full-scale replica of the iconic vessel and numerous personal effects of the crew.

Most impressive is the Batten Conservation Complex, the official preservation facility housing and conserving 210 tons of Monitor artifacts, notably the ship’s gun turret, steam engine and Dahlgren guns. Visitors can look down on the lab and enjoy these artifacts while they undergo conservation in real-time.