Moments in Time: Wilson's Creek - Part IV

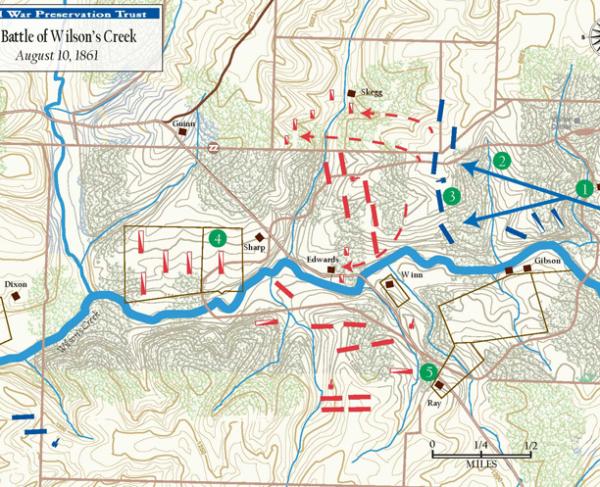

August 10th, 1861, 10 A.M. to 12 A.M.

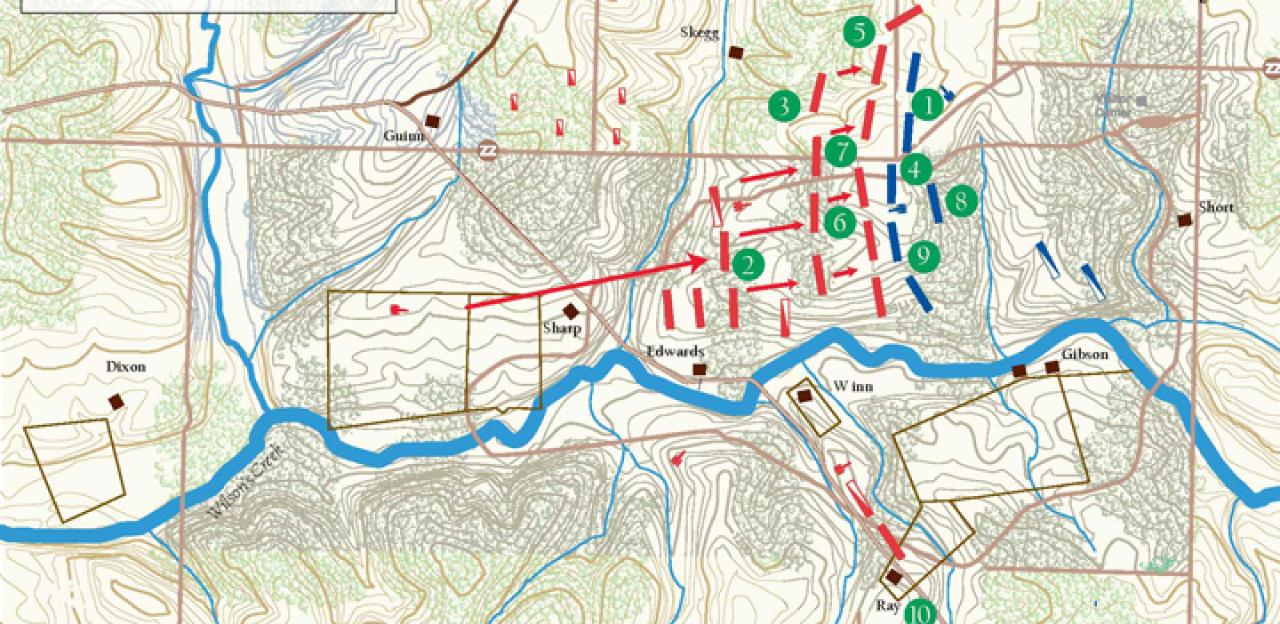

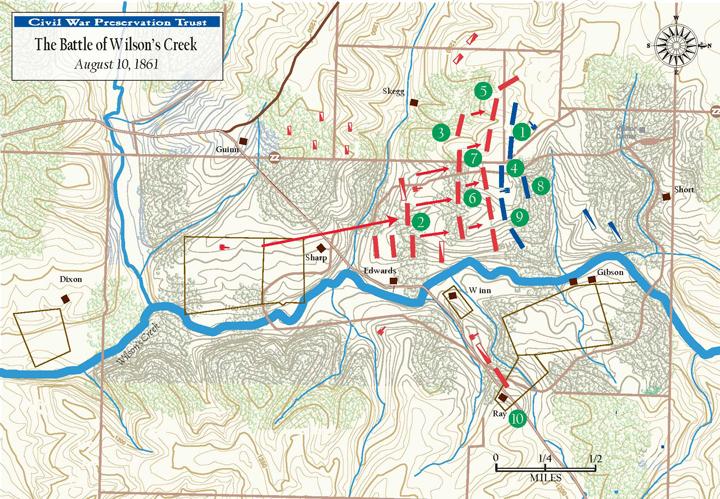

Lyon's forces were stopped cold at the foot of Bloody Hill. They withdrew back up the slope in fragmented groups, trading volleys yard by yard, until they again reached the cover of their cannons at the top. With the threat of Sigel in the south now decisively dealt with, McCulloch turned north and launched a counterattack all down the line.

1. "Life ain't long enough for them to lick us in!"

From the western flank of the Union line Eugene Ware could see thousands of Confederates begin to pour out of the underbrush towards Bloody Hill. Just then a "big regular army cavalry officer on a magnificent horse" appeared and galloped down the length of Ware's regiment, swearing and bellowing encouragement. Ware could tell that the most fierce fight of the day was about to begin.

2. "Totten's [Union] battery seemed to belch forth with renewed vigor....and the fortunes of war appeared to be sending many of our gallant officers and soldiers to their death. There was no demoralization--no signs of wavering or retreat, but it was an hour of great anxiety and suspense."

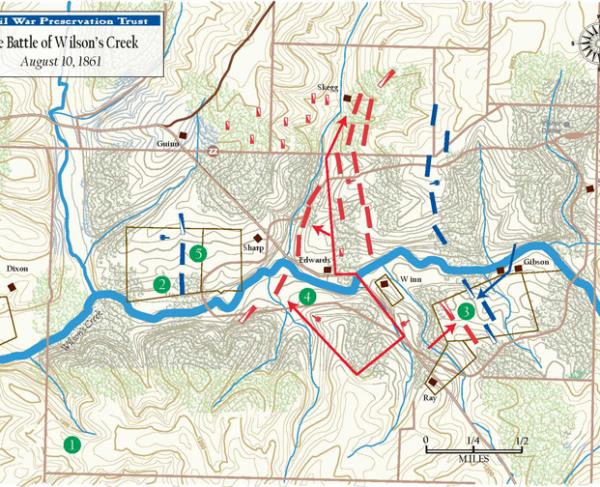

General N. Bart Pearce watched his Missouri Confederates climb into the teeth of the Union guns from his command post just behind the main line. After five hours of fighting there was still no clear winner. Casting about for a plan to change the "fortunes of the day" in his favor, he ordered a flank attack on the left side of the Union line, hoping his infantry would succeed where Greer's cavalry had failed.

3. "You will soon be in a pretty hot place...but I will be near you, and I will take care of you; keep as cool as the inside of a cucumber and give them thunder."

General Sterling Price volunteered to lead the flank attack. He offered soothing words to the young Arkansas soldiers as they marched into position in the cover of the trees behind the main attack. To their right the Arkansans could plainly hear screams, musket fire, and explosions from the slopes of Bloody Hill.

4. "They kept coming...the Rebel infantry, in its charge, worn down to a point, with its apex touched the twelve-pounder [cannon], and one man with his bayonet tried to get the Irish sergeant, who, fencing with his non-commissioned officer's sword, parried the thrusts of the bayonet. I fired at this "apex" at a distance of not over 30 feet. Other secesh were around the guns, but none of them got away. The main body were started back down the slope; the twelve-pounder was then loaded, and assisted their flight."

Eugene Ware was unable to give an accurate count of the number of charges and counter-charges that erupted during the climactic fight on Bloody Hill. In his position on the flank he was desperately fending off the Arkansans who had just been ordered forward.

5. "They opened on us bringing us down like sheep but we never wavered. We did not wait for orders to fire but all of us cut loose at them like wild men, then we dropped to our knees and loaded and shot as fast as we could. We had to shoot by guess as they were on the hill lying in the grass."

Private Ras Stirman of the Third Arkansas participated in the flank attack that was the Confederates' best hope for victory. He was almost surely facing Eugene Ware directly, as Ware recounts that he was part of only a small group in his regiment that practiced how to load and fire lying down. The tall grass thus made Stirman's task all the more difficult. After exchanging murderous volleys for thirty minutes the Arkansans grudgingly withdrew for want of ammunition. The Union flank was secure.

6. "We were pressing up the hill to get to closer quarters, when a ball took me in the pit of the stomach, and for a few minutes I remembered no more."

After surviving the fight in Ray's cornfield earlier that morning, William Watson was nearly killed on Bloody Hill. When he regained consciousness he could feel liquid on his back--he thought the ball had passed through his body, which meant he would surely die. Lifting his canteen to take a final drink, he found it empty. Unimaginably frustrated, he then saw that there wasn't much blood on the hand that had touched his back, and that there was a gaping hole in the side of his canteen. He investigated further and saw that his "Pelican Rifles" belt plate was badly dented. The thick brass had stopped the bullet on its way into his stomach and he wasn't really wounded at all. He staggered upright and went off to find the rest of the 3rd Louisiana.

7. "I heard its chug as it buried itself in the flesh, felt it strike the bone, but it deadened the flesh for several inches around."

Private Henry Cheavens did not have William Watson's luck as he charged up Bloody Hill in a different part of the Confederate line. The Union cannons loaded canister rounds--a sort of incredibly high powered close range buckshot--as the Confederate assault came to within yards of the gun muzzles. A piece of canister snapped the former schoolteacher's femur. This was the decisive moment of the main attack and the Confederates could not break through. They were thrown back down the hill, leaving Cheavens dreadfully wounded in the scrub.

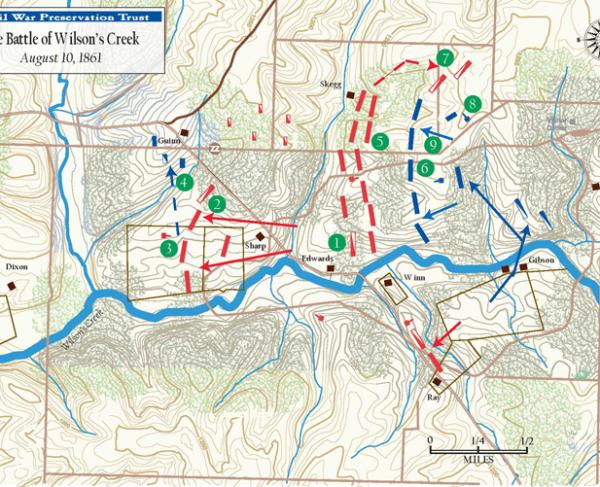

8. "Where is Sigel?"

This was the often repeated question in a huddle of officers that had gathered around Samuel D. Sturgis, Nathaniel Lyon's replacement in command of the Union army. The soldiers on Bloody Hill had held their position valiantly, but they were down to their last minie balls. Even the ammunition that could be scavenged from those who could no longer use it was nearly exhausted. The soldiers had been fighting for six hours and hadn't been able to refill their canteens since 5 o'clock of the previous evening. Having had no communication with Sigel for several hours, Sturgis was aware of the possibility that his fellow general could at any time suddenly appear behind the Confederates and together they could turn the day into a Union victory with one final attack. Sturgis simply did not know until a messenger arrived at this moment bearing word that Sigel had been obliterated in the south. Taking in this new intelligence, Sturgis ordered a retreat back to Springfield.

9. "I was a witness to an act of bravery. . .[Immell] going between the lines at short range and cutting out the dead lead team of Corporal Writtenberry's caisson, and cutting a sapling where it was lodged, and mounting the swing team and taking it out, for which act the line cheered. At close of engagement, his off wheel horse fell fatally wounded, and Corporal [Immell] received three wounds himself. He put a mule in place of the off wheel horse, and saved his six-pounder gun."

McCulloch launched one more attack as the Union army started to filter back down the road to Springfield. Corporal Lorenzo Immell was in the rear-guard of the Union army with yelling Confederates hot on his heels. Seeing an Union cannon abandoned on the front line, Immell resolved to bring it back with him. With the help of Private Nicholas Bouquet he secured the gun through a thick cloud of minie balls and brought it careening back up the road to Springfield. William T. Williams provided testimony at the hearing that resulted in Immell and Bouquet receiving the Congressional Medal of Honor.

10. "We have whipped them. They are gone."

Colonel Richard Weightman, wounded three times in the closing attacks on Bloody Hill, could hear cheering from his bed in the Confederate field hospital that had been hastily set up in John Ray's farmhouse. One of his orderlies arrived shortly before noon and breathlessly told Weightman the news. "Thank God!" Weightman whispered, and died.

The Confederate army could claim victory after Wilson's Creek, but the Union army had fought with great courage and was justifiably reluctant to admit total defeat. Both sides lost around 1,300 men killed, wounded, and captured. Missouri stayed in the Union, but the state was doomed to the convulsions of violent guerrilla campaigns for the duration of the war.

Moments in Time at Wilson's Creek: Introduction | Part I | Part II | Part III

Sources:

Wilson's Creek by William Garrett Piston & Richard W. Hatcher III

The Battle of Wilson's Creek by Edwin C. Bearss

War of the Rebellion Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies Series I. Vol. 3.

Bloody Hill by William Riley Brooksher.

Lyon's Campaign in Missouri by Eugene Ware

Maps originally by Steven Stanley, modified by Sam Smith

Related Battles

1,235

1,095