As longtime Gettysburg Licensed Battlefield Guides and historians, we are somewhat spoiled. That field has a body of historical resources that makes scholars of other sites envious: The battlefield is well preserved; photographers documented the place within days of the fighting; mapmakers issued maps while the battlefield still looked largely as it did to the soldiers; a good number of those who survived the battle wrote about the fighting, and the battlefield in the months, years and decades thereafter. Books, monument dedications and reunions resulted in even more accounts and documentation. Many battlefields have some of these resources, but few — if any — have so many dated so close to the event.

The Antietam Battlefield is one of those battlefields that has the resource “superfecta”: preserved land, early photography and cartography and ample written documentation. But there was one resource area in which Gettysburg reigned supreme — it boasted the only battlefield with a wartime map denoting soldier burials and horse-death locations covering most of the field … until now.

Ever since Tim (Smith) happened upon the Elliott Burial Map for Antietam, digitized in the collections of the New York Public Library, historians and enthusiasts have been examining the map and the battlefield anew, armed with visual information that had not been used by any historian, interpreter or park steward since the map was published in 1864. Most of the dead soldiers represented on the map are only identified by their army while 30 groups of gravesites are identified by regimental designation, and more than 50 soldiers are identified by name.

Before news of the map’s emergence became public on June 16, we, along with Andrew Dalton, executive director of the Adams County Historical Society, and Antietam National Battlefield historian Brian Baracz, started comparing it with other, known primary sources. Did the soldiers fall where we thought they fell? Do the identified graves line up with the written record? And most important to these two photo historians, did the map align with the photographic and other visual records? While Elliott’s map is imperfect, the answer to all the above is a resounding “yes.”

Burying the Dead

Civil War soldiers who died in battle were usually buried where — or very close to where — they fell. Therefore, if Elliott’s map is correct, it is a clear representation of where the fighting was heaviest. However accurate, the picture is not complete: Four soldiers were wounded for every man who was killed in combat, and none of them are accounted for by the map. Nor are those whose wounds proved mortal days or weeks after soldiers were moved to hospitals away from the field.

Nonetheless, Elliott’s map depicts more than 5,800 soldier graves. The burial work was a massive task performed mostly by the Union army. The burial process was in part captured on the glass plates of Alexander Gardner and his crew, under the employ of famed photographer Mathew Brady. Burials were also described by early battlefield visitors and soldiers alike. Speaking at the dedication of his regimental monument along the Bloody Lane years later, S. M. Whistler of Company E, 130th Pennsylvania said:

The weather was phenomenally hot, and the stench from the hundreds of black, bloated, decomposed, maggoty bodies, exposed to a torrid heat for three days after the battle was a sight truly horrid, and beggaring all power of verbal expression…. Just over there in Mumma’s field in one ditch you placed 185 Confederate corpses, the one on top of the other, and indecorously covered them from sight with clay. In other ditches lesser numbers were similarly buried. Time and circumstances forbade a more humane course than this.

The grisly task was repeated in reverse when Union remains from the field were reinterred in Antietam National Cemetery, established in late 1866. Confederate cadavers remained in the ground for roughly 10 years before they were removed from the battlefield to Rose Hill Cemetery in Hagerstown, Maryland.

In his Antietam: The Photographic Legacy of America’s Bloodiest Day, William A. Frassanito demonstrated that burial crews were graphically depicted by photographers and sketch artists near the Bloody Lane, along the Hagerstown Road and on and near the “Epicenter” tract preserved by members of the American Battlefield Trust in 2015.

There are two instances in which the Elliott Map identifies a burial by name that is confirmed by one of Alexander Gardner’s photos. William Frassanito researched both soldiers — Pvt. John Marshall of the 28th Pennsylvania and Pvt. Edward Miller of the 51st New York. The map and the Gardner photos are in near-perfect accordance with one another. Although these are the only two instances in which photos corroborate soldier identities on the map, these examples serve to remind us that each of the thousands of hashmarks on the Elliott Map — and indeed each of the untold thousands on other battlefields — represent a real person, one with a name, a family and a story.

The Bloody Lane

Battlefield Today:

Historic Photos & Elliott Map:

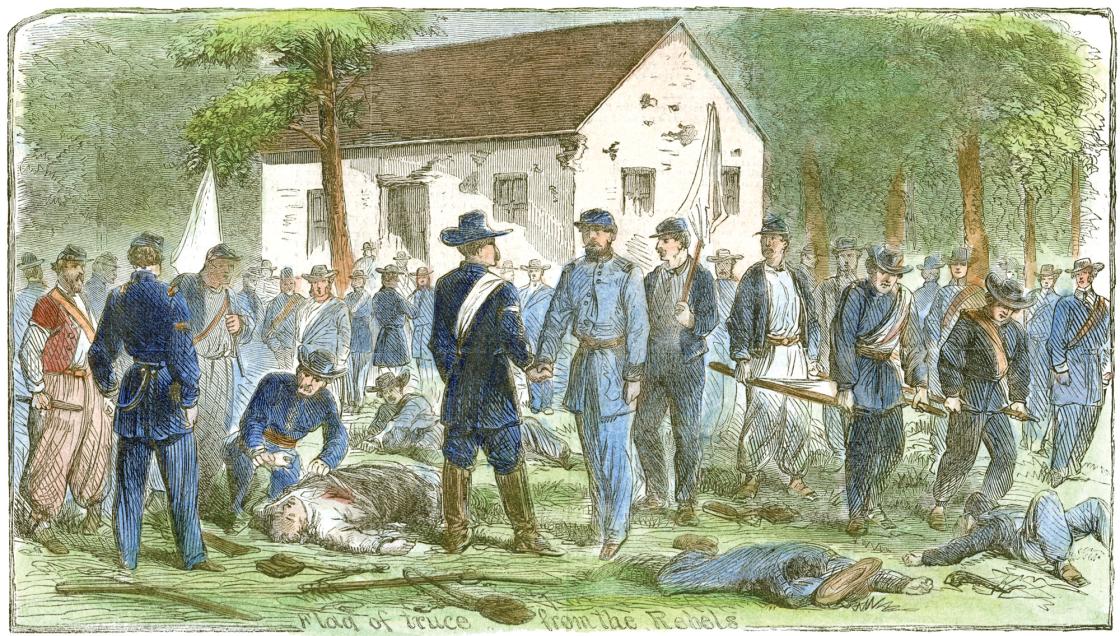

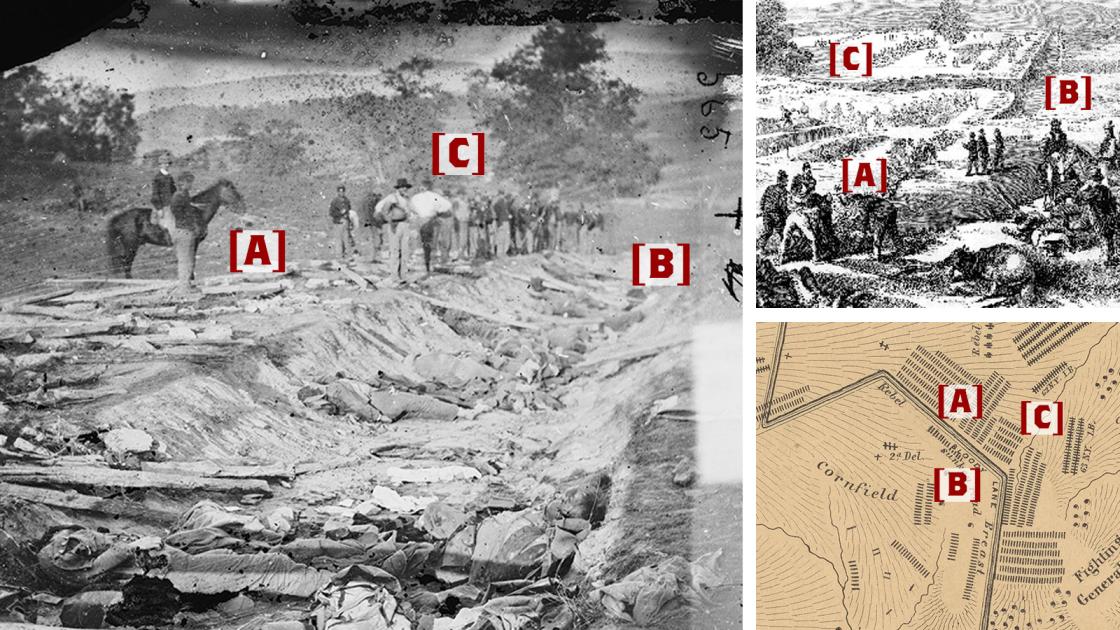

The Sunken Road, or Bloody Lane, was particularly well documented. One of the three photos taken in this area by Alexander Gardner and a drawing by artist Frank Schell, converted into an engraving for Frank Leslie’s Illustrated newspaper, both likely depict the same unit. The 130th Pennsylvania, “having incurred the displeasure of its brigade commander, was honored in the appointment as undertaker-in-chief.” Existing accounts support the civilians in the drawing being on the scene — early battlefield tourists — as burial operations moved dead soldiers from the hard-packed lane to nearby trenches. (A) The Elliott Map generally agrees with the photo and the sketch. All three views also depict the same bend in the Bloody Lane (B) and the location of the Roulette Lane (if not the lane itself) (C), which was the line of the Union approach to the Sunken Road.

The Hagerstown Pike

Battlefield Today:

Historic Photos & Elliott Map:

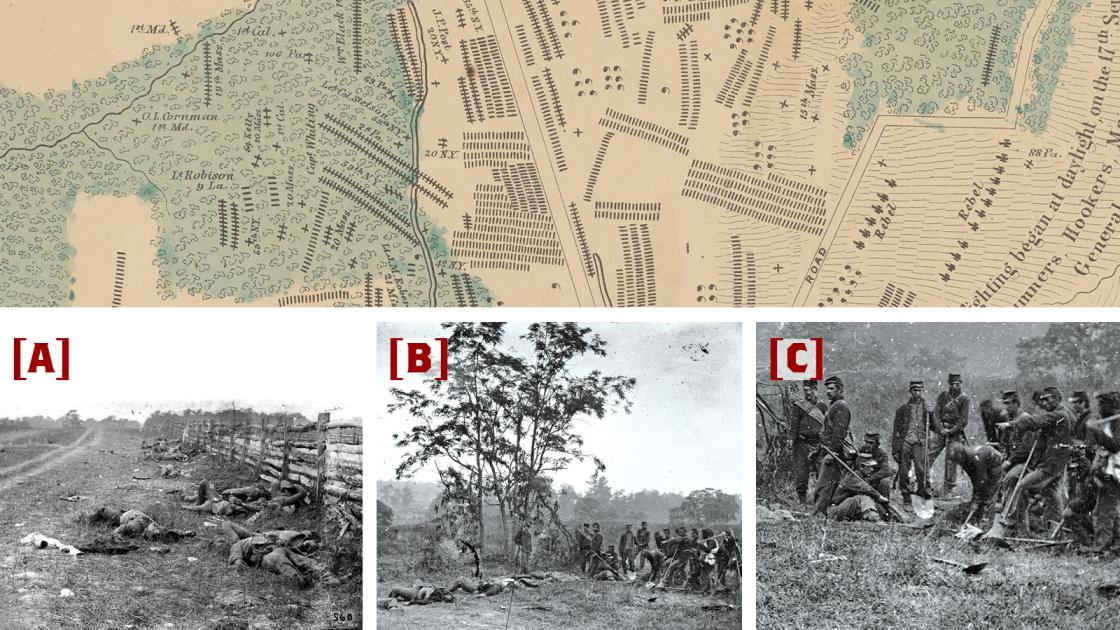

Historian Frassanito divined the location of six photographs taken along the Hagerstown Pike by Gardner’s crew. The most-commonly reproduced (A) shows dead Confederate soldiers after a fierce fight at the sturdy but not impenetrable fence along the Pike (visible through the slats to the right of the fence). The approximately 15 corpses in evidence here are a small fraction of the hundreds of soldiers denoted on the Elliott map between the Pike and the West Woods.

The tree visible on the horizon at left center is actually a small group of trees near which a burial crew is performing its grisly work (B). Pausing their work for the camera, the men display the army shovels and pickaxes used to dig mass graves, for which the remains at left are destined. The photo detail that focuses on the burial crew better shows the soldiers’ faces, the man casually leaning on a stack of muskets and two upright shovels (C), surely to be soon used again in this enormous, terrible and sad task.

The Grave of John Marshall

Battlefield Today:

Historic Photos & Elliott Map:

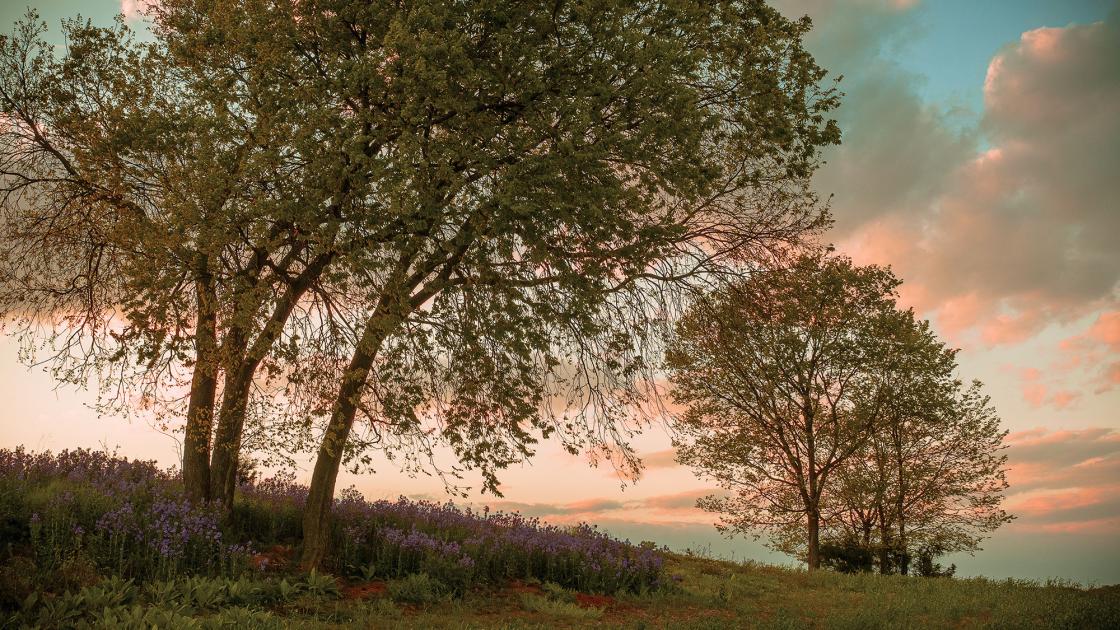

One of the most poignant images recoded during the Civil War is (A) “A Lone Grave on Battle-field of Antietam.” Examining the original negative under magnification during the 1970s, photographic historian William Frassanito deciphered the inscription on the headboard (at the base of the tree) as John Marshall, 28th Pennsylvania. (B) With its striking location at the base of a prominent knoll in the middle of the Antietam Battlefield, the grave of this 50-year-old native-Irish stone mason from Allegheny City attracted the attention of Alexander Gardner. His grave also attracted the attention of the surveyors responsible for the S. G. Elliott Burial Map. (C) The photo was taken and is marked on the map at the same place — 160 yards northeast of the modern visitor center, where a tree of similar size grows today. Marshall’s remains were recovered and moved to the Antietam National Cemetery, where he reposes in grave #3,600.

Evidence: The Grave of Edward Miller

Battlefield Today:

Historic Photos & Elliott Map:

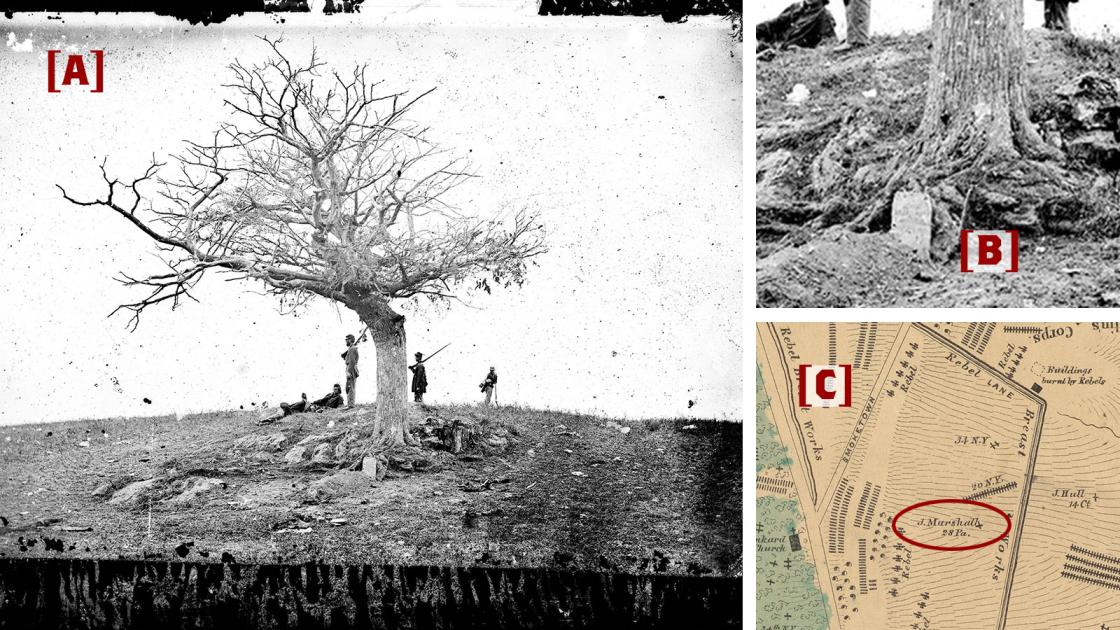

Another well-known Gardner photo, and one whose location is easy to find, is that of a soldier standing among freshly dug graves along the stone wall next to Burnside Bridge, just a few days after the battle. Gardner also recorded a version of the same wall from farther away, which is shown here as well. In his Antietam, William Frassanito spotted 12 headboards against the wall and found that nine of them read 51st New York — one of the two regiments that crossed Burnside Bridge in the successful attack. Using records of those men of the 51st who died at Antietam, he was able to decipher the names of four of the deceased. Of these, one appears on Elliot’s map: Pvt. Edward Miller, dead at age 18 and now resting in grave #782 of Antietam National Cemetery.

Questions arise when examining the photos here along with Elliott’s map. First, the photos clearly show Miller’s and other headboards near and parallel to the stone wall, but the map shows them as perpendicular and with Miller’s grave farthest from the wall. Furthermore, although there are more than 40 Union graves shown on the map in this area, the broader image only shows disturbance near the wall. Are we to take Elliott’s work as more general than specific? If so, how do we explain the accuracy in other areas?

Conclusion

In the end, Elliott’s map is like any historical source — we must use it carefully. We must be skeptical of what it tells us. No doubt, this is precisely what good historians will do with Elliott’s map in the years, decades and centuries to come.

Related Battles

12,401

10,316