Embargos: Economic Warfare on the Eve of the War of 1812

The outbreak of the Napoleonic Wars marked a new kind of military conflict, as war raged across the world, from French and British colonies in the Americas and Asia to European battlefields. Victory was not determined solely on the battlefield; now, nations attempted to defeat their enemies by suffocating their trade and cutting off their supplies. The United States was young and militarily weak, but a necessary part of the global network of 19th Century commerce, and it was soon engaged in commercial warfare. American embargoes attempted to peacefully achieve foreign policy goals and restore free trade. Unfortunately, the embargoes failed to prevent the War of 1812, and peace would not be restored between the United States and Britain until early 1815.

When Anglo-American trade grew in the 1790s after the enactment of Jay’s Treaty, France angrily responded by targeting American shipping in the undeclared Quasi-War. French and American diplomats restored relations and ended that conflict at the Convention of 1800. A temporary peace was established the following year between France and Britain by the Treaty of Amiens. Although peace made the world far safer for American commerce, it also reduced the economic advantage the United States had as a neutral power.

The peace did not last long. When war between Britain and France broke out again, American profits rose accordingly. The re-export trade was especially lucrative. American ships transported goods between France and the Caribbean but stopped in an American port in between. Because the trade route included an American port, the ships would technically be obeying a British maritime regulation known as the Rule of 1756, which was intended to limit neutral countries’ trade with Britain’s enemies. But in 1805, the British began to enforce the rule more strenuously, and targeted American shipping once more, seizing hundreds of ships. Again, the Americans appealed to diplomacy. The resulting negotiations created the Monroe-Pinkney Treaty, which favored American trade but failed to end impressment. President Thomas Jefferson, frustrated that the British had not conceded on impressment, refused to submit the treaty to the Senate for approval and it never took effect.

While negotiations for the Monroe-Pinkney Treaty were underway, the Non-Importation Act of 1806 passed in Congress. Although its implementation was delayed during active negotiations, it banned the importation of some manufactured British goods and revived some of the successful boycott policies of the American Revolution.

Relations between Britain and the United States declined severely during 1806 and 1807. The Monroe-Pinkney Treaty failed, and in the summer of 1807, the Chesapeake Affair almost brought the two nations to war. A British warship, the H.M.S. Leopard, attacked and boarded the American Chesapeake in search of deserters, sparking outrage across the United States. The British government disavowed the attack but still maintained their right to impressment. At the same time, commercial warfare escalated between France, which now controlled continental Europe, and Britain. The French “Berlin Decree” proclaimed a blockade of Britain; Britain soon responded with a series of Orders-in-Council prohibiting most European trade. Although Americans protested the decrees and smuggling was rampant, hundreds of American ships were seized by both sides in the years leading up to 1812.

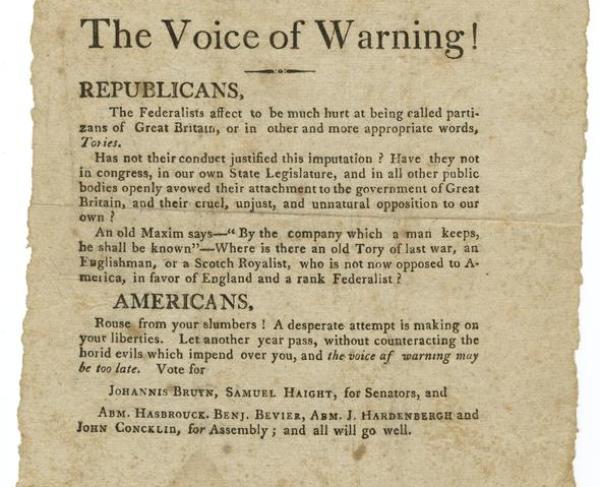

The increasing tensions with both European great powers led the American government to restrict trade more and more. Democratic-Republicans, including Jefferson, generally supported trade restrictions, professing a strong faith in the importance of American trade for the European powers. Federalists, whose center of support was in trade-dependent New England, tended to fear the consequences of lost trade. When American commercial restrictions increased and the economy suffered, support for the Federalists grew accordingly.

The strongest and most damaging measure was the Embargo Act of 1807. Controversial even among Democratic-Republicans, it essentially banned all exportation by sea. It sent the young American economy into a depression, and merchants and farmers suffered alike. Smuggling flourished, and many merchants found ways to evade the law and excuses to dock at foreign ports—for example, ships trading along the coast would suddenly be blown off course or would be enlisted to pick up American property abroad. The Enforcement Act of 1809 attempted to close some of these loopholes, but the original embargo was repealed in March of the same year. The Non-Intercourse Act replaced the Embargo Act and allowed trade with all foreign nations except Britain and France.

Non-exportation appeared to be damaging the American economy more than encouraging free trade policies by either Britain or France, so the Non-Intercourse Act was repealed, too, in 1810. It was replaced by more restrictions on the importation of European goods, in the hopes that the loss of American markets would have a greater effect on the European powers’ policy than the loss of American goods had. France promised to end some of its own restrictive policies but continued to prey on American shipping; Britain made no such promises, and more non-importation measures were passed accordingly.

Anglo-American trade did not recover until the war was over. The failure of American commercial warfare and the ongoing restrictions on trade and attacks on shipping drove the two nations closer and closer to war. The British alliances with Native American nations on the northwestern frontier made many Americans feel that they were at war with the British Empire already, especially after the Battle of Tippecanoe was fought in 1811. War was officially declared on June 18, 1812.

Although the embargo failed to substantially change European trade restrictions and prevent the War of 1812, it had other significant effects. The damage it did to the American economy increased support for the Federalist Party and discouraged even strong Democratic-Republicans from further economic warfare, pushing some to become war hawks instead. Finally, the dearth of manufactured goods encouraged the development of American industry and made possible the rapid industrialization of the United States later in the 19th century.

Further Reading:

The War of 1812: A Forgotten Conflict by Donald R. Hickey

Madison’s Alternatives: The Jeffersonian Republicans and the coming of war, 1805-1812 by Robert A Rutland

The Civil War of 1812: American Citizens, British Subjects, Irish Rebels, & Indian Allies by Alan Taylor

Ruinous and Unhappy War: New England and the War of 1812 by James H Ellis