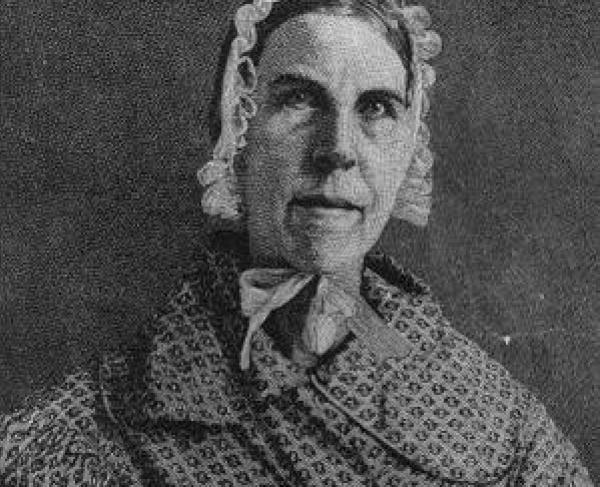

Sarah Emma Edmonds

Sarah Emma Edmondson was born in New Brunswick, Canada in December of 1841. Her father was a farmer who had been hoping for a son to help him with the crops; as a result, he resented his daughter and treated her badly. In 1857, to escape the abuse and an arranged marriage, Edmondson left home, changing her name to Edmonds.

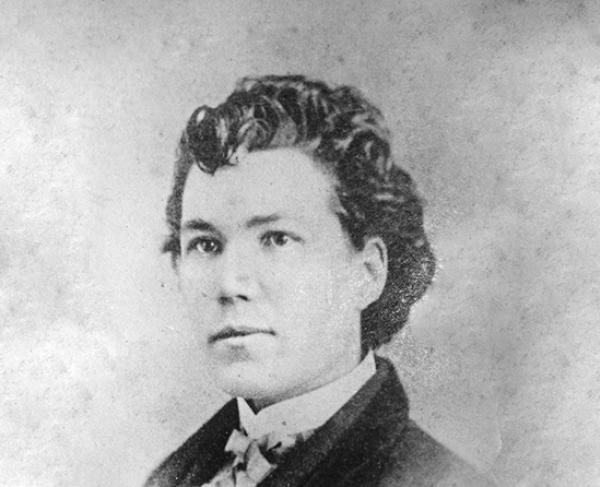

Edmonds lived and worked in the town of Moncton for about a year, but always fearful that she would be discovered by her father, she decided to immigrate to the United States. In order to travel undetected and to secure a job, she decided to disguise herself as a man and took the name Franklin Thompson. She soon found work in Hartford, Connecticut as a traveling Bible salesman.

By the start of the Civil War in 1861, Edmonds was boarding in Flint, Michigan, continuing to be quite successful at selling books. An ardent Unionist, she decided that the best way to help would be to enlist under her alias, and on May 25, 1861, Edmonds was mustered into the 2nd Michigan Infantry as a 3 year recruit.

Although Edmonds and her comrades did not participate in the Battle of First Manassas on July 21, they were instrumental in covering the Union retreat from the field. Edmonds stayed behind to nurse wounded soldiers and barely eluded capture to return to her regiment in Washington. She continued to work as a hospital attendant for the next several months.

In March of 1862, Edmonds was assigned the duties of mail carrier for the regiment. Later that month, the 2nd Michigan was shipped out to Virginia as part of General McClellan’s Peninsula Campaign. From April 5 to May 4, the regiment took part in the Siege of Yorktown.

It was during this time that Edmonds was supposedly first asked to conduct espionage missions. Although there is no definitive proof that Edmonds ever acted as a spy, her memoirs detail several of her exploits behind enemy lines throughout the war, disguised variously as a male “contraband” and an Irish peddler.

On May 5, 1862, the regiment came under heavy fire during the Battle of Williamsburg. Edmonds was caught in the thick of it, at one point picking up a musket and firing with her comrades. She also acted as a stretcher bearer, ferrying the wounded from the field hour after hour in the pouring rain.

The summer of 1862 saw Edmonds continuing her role as a mail carrier, which often involved journeys of over 100 miles through territory inhabited by dangerous “bushwhackers.” Edmonds’ regiment saw action in the battles of Fair Oaks and Malvern Hill, where she acted once again as hospital attendant, tending to the many wounded. With the conclusion of the Peninsula Campaign, Edmonds returned with her regiment to Washington.

On August 29, 1862, the 2nd Michigan took part in the Battle of Second Manassas. Acting as courier during the battle, Edmunds was forced to ride a mule after her horse was killed. She was thrown into a ditch, breaking her leg and suffering internal injuries. These injuries would plague her for the rest of her life and were the main reason for her pension application after the war.

During the Battle of Fredericksburg on December 11-15, Edmonds served as an orderly for her commander, Colonel Orlando Poe. While her regiment did not see much action, Edmonds was constantly in the saddle, relaying messages and orders from headquarters to the front lines.

In the spring of 1863, Edmonds and the 2nd Michigan were assigned to the Army of the Cumberland and sent to Kentucky. Edmonds contracted malaria and requested a furlough, which was denied. Not wanting to seek medical attention from the army for fear of discovery, Edmonds left her comrades in mid-April, never to return. “Franklin Thompson” was subsequently charged with desertion.

After her recovery, Edmonds, no longer in disguise, worked with the United States Christian Commission as a female nurse, from June 1863 until the end of the war. She wrote and published her memoirs, Nurse and Spy in the Union Army, the first edition being released in 1864. Edmonds donated the profits from her book to various soldiers’ aid groups.

Edmonds married Linus Seelye in 1867 and they had three children. In 1876, she attended a reunion of the 2nd Michigan and was warmly received by her comrades, who aided her in having the charge of desertion removed from her military records and supported her application for a military pension. After an eight year battle and an Act of Congress, “Franklin Thompson” was cleared of desertion charges and awarded a pension in 1884.

In 1897, Edmonds was admitted into the Grand Army of the Republic, the only woman member. One year later, on September 5, 1898, Edmonds died at her home in La Porte, Texas. In 1901, she was re-buried with military honors at Washington Cemetery in Houston.