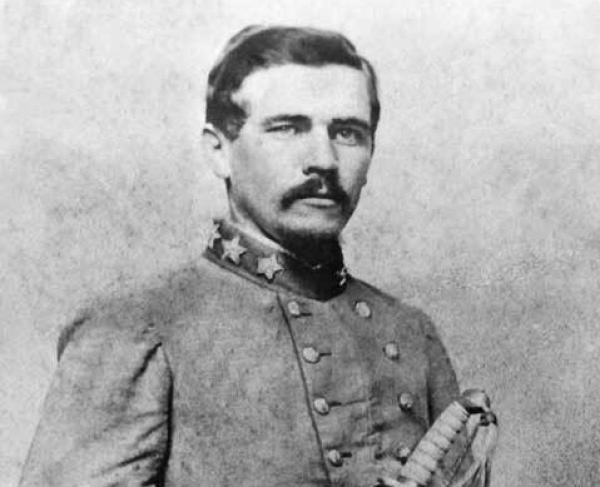

Nathaniel Banks

Nathaniel Prentice Banks was born on January 30, 1816 in Waltham, Massachusetts. As a young boy, Banks had the luxury of receiving an education until the age of fourteen when his family went into financial hardship. Banks was forced to take a job as a bobbin boy at a local textile mill. He received the name “Bobbin Boy Banks” and the name stayed with him for his entire life. As a young adult, Banks often visited Boston to attend lectures from prominent Bostonians and perfected his oratorical skills. After receiving some success as an orator, Banks quit the textile mill and pursued a career in politics.

In 1848, Banks successfully ran for the Massachusetts State legislature and in 1850 Banks was the Speaker of the Massachusetts House of Representatives. In 1852, Banks was successful in his run for United States Congress. In 1856, Banks became Speaker of the House and helped form the first Congressional Coalition in American history. In 1858, Banks ran for Governor of Massachusetts and beat incumbent Henry Gardner. As Governor of Massachusetts, Banks helped to support abolition by signing a bill to allow Anthony Burns, an escaped slave, to remain free in Massachusetts. Banks also supported a bill that forced naturalized citizens to wait two years to vote and Banks vetoed legislation that would lift restrictions on militia enrollment to only whites after John Brown’s Raid in Harper’s Ferry, Virginia. In 1860, Banks ran as a presidential candidate for the Republican Party after being succeeded as governor by John Albion Andrew. Due to his influence and bipartisan support in Washington from his years as Speaker of the House and Congressman, Banks was a promising candidate for the presidency. However, many radicals did not support Banks, and his candidacy fell through.

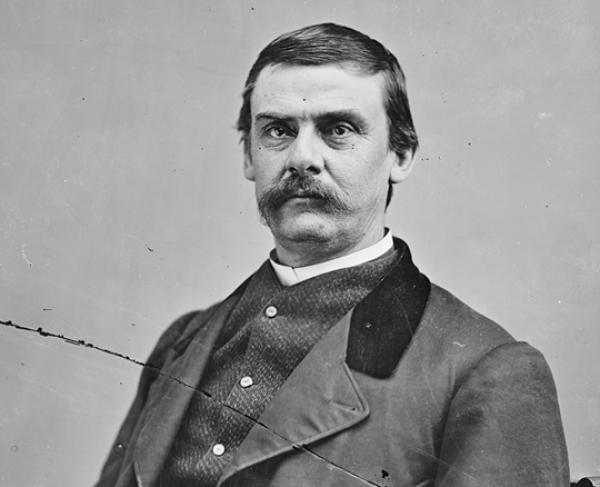

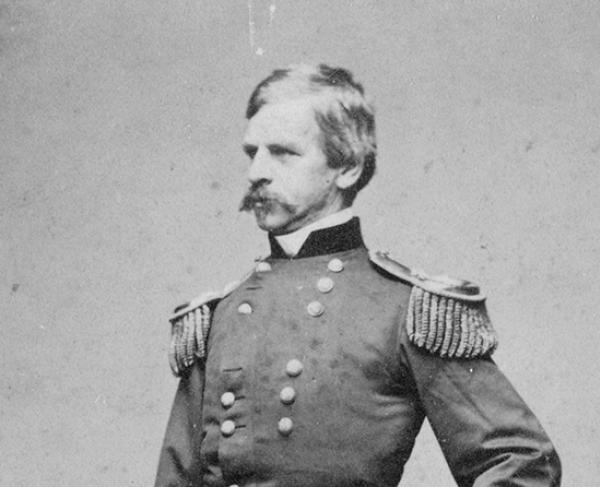

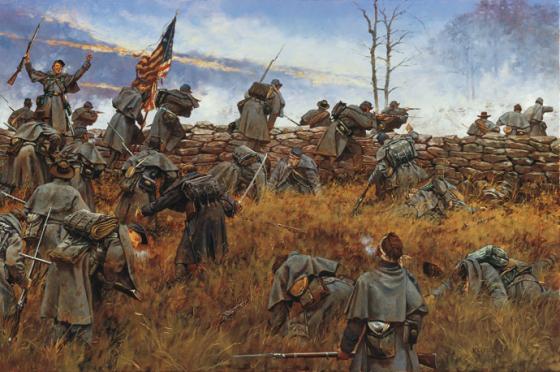

On May 16, 1861, President Abraham Lincoln appointed Banks as Major General. Due to his heavy influence in national politics, Lincoln believed that Banks could attract more people to join the Union cause. Lincoln’s first assignment to Banks was in August of 1861 where he was assigned to maintain control of Western Maryland to prevent Maryland from seceding. The first combat action that Banks saw was in the Shenandoah Valley against Lieutenant General Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson in 1862. Banks was tasked with keeping Washington, D.C. protected, as well as prevent “Stonewall” Jackson from reinforcing Richmond as General George B. McClellan made his way through the Virginia Peninsula to capture Richmond. On March 23, 1862, Banks experienced his first engagement at the First Battle of Kernstown. Following Kernstown, Banks and Jackson engaged once again at the Battle of Front Royal on May 23. Two days later, Banks retreated to Winchester, Virginia where the two generals clashed once again at the Battle of First Winchester.

Following the Shenandoah Valley Campaign, in July of 1862 Banks was ordered by Major General John Pope to Culpeper, Virginia. On August 9, 1862, Banks commanded his men at the Battle of Cedar Mountain against his rival from the Shenandoah Valley Stonewall Jackson. After the Battle of Cedar Mountain, Banks was stationed at Bristoe Station and did not fight at the Second Battle of Bull Run. On September 12, 1862, Banks was unexpectedly removed from command in the Army of the Potomac.

In November of 1862, President Lincoln reassigned Banks as commander of the Army of the Gulf. Lincoln realized that Banks had an uncanny ability to recruit soldiers, and asked Banks to organize a force of 30,000 soldiers from the New England region. As former Governor of Massachusetts, Banks had deep connections to each state’s governments. Recruitment efforts were extremely successful. By December of 1862, Banks said from New York to Louisiana. Banks replaced Major General Benjamin Butler, who thought little of Banks’ leadership capabilities. Despite Butler’s personal disagreements, he welcomed Banks to Louisiana. Banks’ main issue was ensuring that he could successfully suppress Confederate forces in New Orleans, as well as cater to radical Republicans in Washington, D.C. With Banks’ moderate political ideology and moderate approach to administration, being able to please both sides remained a challenge for Banks. Banks’ first order of business was to prohibit pillaging. Many soldiers, however, disobeyed Banks actively. Banks undid many of the policies that his predecessor had in place. Banks freed civilians that were previously detained, and Banks also reopened churches that were not pro-Union. Banks instituted public works projects and education programs for freed slaves. However, once Southerners regained control of Louisiana, many of the programs were shut down.

In 1863, Banks was tasked with taking Port Hudson in Eastern Louisiana to help alleviate pressure from Ulysses S. Grant. After a continuous siege, on July 9th, 1863, the Confederate forces surrendered having run out of supplies and receiving word that Vicksburg had also surrendered. In 1864, Banks and Ulysses S. Grant were tasked with capturing parts of Northern Texas. Called the Red River Campaign, both generals believed the campaign to be insignificant and instead wanted to capture Mobile, Alabama. Banks never made it to Mobile, following a loss at the Battle of Mansfield, in De Soto Parish, Louisiana. Banks and his men were forced to retreat. Arriving in Alexandria, Louisiana, Banks’ army attempted to continue their retreat aboard Admiral David Dixon Porter’s fleet. With water levels low in the channel, the men were forced to build dams under heavy fire. In two days, the dams were completed, raising the water level high enough to continue the retreat. With the Confederates holding the Red River until after General Robert E. Lee’s surrender in 1865, the Red River Campaign was considered a failure.

Following Banks’ Civil War service, Banks immediately ran for Congress. Banks won the election and took office from 1865 to 1873. Throughout his terms, Banks was a supporter of Manifest Destiny and wanted the United States to control Canada, the Russian territory of Alaska, the Dominican Republic, and the Danish West Indies (today the United States Virgin Islands which were sold to the United States in 1917 for $25 million). After losing his reelection campaign in 1873, Banks decided to invest in a railroad company with Civil War veteran and brother in arms John Frémont. Banks was also elected to the Massachusetts State Senate in 1873, however, he was defeated in 1879. In 1888, Banks was once again elected to the United States Congress, however, his health was failing. After serving one term, Banks retired to his hometown of Waltham, Massachusetts.

After Banks’ short term in office, President Rutherford B. Hayes appointed him as a United States marshal in the Boston area. After Rutherford B. Hayes's presidency, Banks’ wife wrote to President Grover Cleveland and asked him to allow Banks to continue working in the position. She explained, “His life and his energies have been devoted to his country… he has made no provision for the future, and now, almost worn-out with service, he finds he has nothing for himself or for those who are dependent on him.” Her plea worked, and President Cleveland allowed him to work as a marshal for two more years until he was relieved from the position. Afterward, Banks’ health greatly declined, and his mental health worsened. In August of 1894, he was placed in a mental asylum. However, the conditions of the asylum did little good for his mental health, and he was placed back in the care of his family in Waltham. On September 1, 1894, at eight o’clock in the morning, Nathaniel Prentice Banks passed away at the age of seventy-eight.

Nathaniel Banks’ legacy lives on after his death. In the late 1890s, Fort Banks was named in his honor. In the central square of Waltham, Massachusetts, a statue of him stands tall. At the statue dedication ceremony, Herbert Parker, the Massachusetts Attorney General at the time of the unveiling said to the crowd, “[Banks] sought no renown, he craved no reward, save that which might be part of the fame and glory of his State and nation, and there his memory is secure.”

Further Reading:

- Pretense of Glory: The Life of General Nathaniel P. Banks By: James G. Hollandsworth Jr.