Union troops surge over the "Bloody Angle" at Spotsylvania.

The manner in which Civil War soldiers fought seems foolish today. Advancing in large, tight formations toward well-fortified positions appears suicidal. Civil War soldiers were not stupid. They had no wish to die—they were using the modern tactics of the times. Advancing in tight ranks and delivering overwhelming, concentrated small arms fire against your enemy was an essential part of fighting the Civil War

Of the thousands of attacks that involved thousands of soldiers each, Pickett’s Charge at Gettysburg, July 3, 1863, stands out as the most well-known. But this famous attack of roughly 12,000 soldiers was far from the largest, bloodiest, longest, or most sustained. Consider these other lesser-known, but arguably more notable, Civil War charges, assaults and attacks.

The Largest Assault of the Civil War: General Lee’s attack at Gaines’ Mill, June 27, 1862

Not long after taking command of the Army of Northern Virginia, Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee hatched a plan to drive Union Gen. George B. McClellan’s Army of the Potomac away from Richmond, Virginia. Lee moved most of his army north of the Chickahominy River and attacked an isolated part of McClellan’s army under Union Gen. Fitz John Porter. On June 27, 1862, the fighting that erupted at Gaines’ Mill was the bloodiest of the week-long battles known as the Seven Days.

After several unsuccessful attempts to break the Union line at Gaines’ Mill, at 7:00pm Lee ordered the bulk of his entire force to assault the strong, Union position. Precious little daylight remained when the Confederates attacked along a two-mile front. The aggressive Confederate Gen. John Bell Hood, spearheaded the attack and others joined the fray. With more than 30,000 soldiers (by some calculations, the number should really be closer to 50,000) in a general simultaneous movement, Confederates at Gaines’ Mill carried the Union position before nightfall and could rightly claim to have participated in the largest assault of the Civil War.

The Largest Flank Attack of the Civil War: Stonewall Jackson’s assault at Chancellorsville, May 2, 1863

On the morning of May 2, 1863, Confederate General Stonewall Jackson led his corps on a 12-mile march to gain the Union right flank west of Chancellorsville, Virginia. All day long his men tromped and by late afternoon they arrived squarely upon the exposed flank of the Union 11th Corps, commanded by Gen. Oliver O. Howard. Jackson approached from the west but almost all of Howard’s force faced generally southward.

The massive Confederate force unfolded astride the Orange Turnpike like a giant accordion. The movement was so enormous that it took hours to complete. At last, however, about 20,000 Confederates had arrayed themselves in lines of battle, several ranks deep and two miles wide. When Jackson’s men emerged from the woods some startled Yankees stood and fought but the outmatched Union soldiers had no real hope of actually blocking the Confederate juggernaut. Jackson had crushed the Union right flank and was prepared to push his enemy into the Rappahannock River. As darkness made forward movement almost impossible, it also brought on the wounding of Stonewall Jackson, which would lead to his death the following week—one of thousands of casualties in the greatest flank attack of the Civil War.

The Most Fortuitous Charge of the Civil War: General Longstreet’s attack at Chickamauga, September 20, 1863

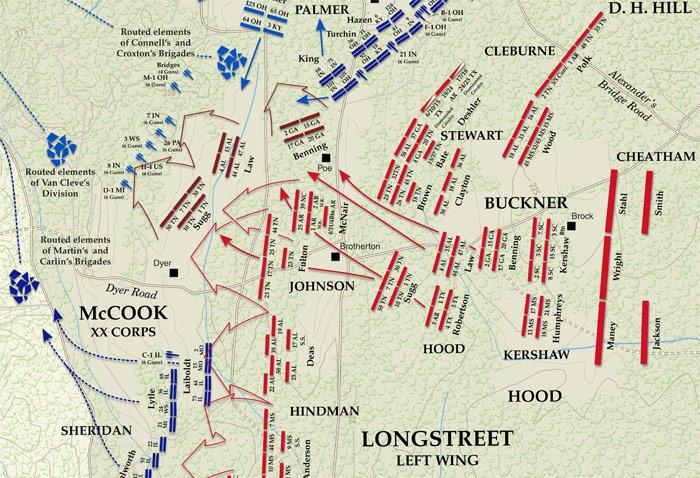

In early September 1863, Union Gen. William S. Rosecrans captured Chattanooga, Tennessee without a fight. As Rosecrans moved into Georgia, his opponent, Confederate Gen. Braxton Bragg attacked a portion of Rosecrans’ army along the banks of Chickamauga Creek. The second largest battle of the Civil War had begun. For two days, the armies fought. They struggled mightily on September 19th. But on the 20th Rosecrans mistakenly thought there was a gap in his line which he aimed to fill. In doing so, he created a large and dangerous gap on his right flank, near the Brotherton farm.

During the battle, Bragg had received reinforcements under Gen. James Longstreet, who had just completed a tortuous journey on foot and by rail from northern Virginia. Longstreet was given command of the left wing of Bragg’s army and ordered to attack the Union right. He moved more than 20,000 Confederate soldiers on a narrow front and, entirely by chance, directly into the gap in the Union line. The power of his assault shattered the Union right flank and drove far into the Union rear. A full one-third of the Union army, including its commander was driven from the field in the most fortuitous attack of the Civil War.

The Most Compact Large-Scale Attack of the Civil War: General Hancock’s assault at Spotsylvania, May 12, 1864

Union Gen. U.S. Grant began his spring campaigns of 1864 by moving various armies at once on five fronts. His largest effort was with his eastern armies, with which he traveled. Grant failed to achieve success at the Wilderness and then moved onto Spotsylvania Courthouse where Grant and his opponent Confederate Gen. Robert. E. Lee engaged in a two-week struggle which proved to be one of the bloodiest of the Civil War. After the partial success of Union Gen. Emory Upton’s 12-regiment compact attack at Spotsylvania on May 10, 1864, Grant ordered Gen. Winfield S. Hancock to lead a much larger assault two days later, with more than 40 regiments, upon the strong Confederate position known as the Mule Shoe, but forever thereafter as the Bloody Angle.

At first light, Hancock’s "battering ram" of some 20,000 men smashed into the Confederate line, broke through, captured thousands of Southerners and then stalled. Powerful Confederate counterattacks ensued and even with more than 15,000 reinforcements, the Union soldiers failed to achieve victory. For 20 hours, American’s fought each other in the closest proximity, a result of the most compact large scale attack of the Civil War.

The Largest Cavalry Charge of the Civil War: Torbert’s grand charge at Third Winchester, September 19, 1864

Tasked with rendering the Shenandoah Valley useless to Confederates, Union Gen. Philip Sheridan, commander of the new Army of the Shenandoah, sought to deal with the main Confederate force in the Valley under Confederate Gen. Jubal Early. On September 19, 1864, Early and Sheridan clashed at the Battle of Third Winchester. Just before noon the bloodiest battle fought in the Shenandoah commenced. Early parried Sheridan’s thrusts until late afternoon.

Unfortunately for Early, Sheridan had three powerful cavalry divisions which numbered almost as many troopers as Early had infantry. Union cavalry chief Gen. Alfred Torbert unleashed two of his three divisions in an attack up the Valley Pike. While Union infantry pressed hard on Early’s front, Torbert’s troopers attacked in front and threatened the Confederate rear. The Southerners offered stubborn resistance at every fort, fence line and barricade they could find, but by nightfall, the city of Winchester was in Union hands. The Union cavalry charges were several but the final attack involved as many as 8,000 troopers in the largest cavalry charge of the Civil War.

The Civil War’s Deadliest Attack for General Officers: General Hood’s charge at Franklin, November 30, 1864

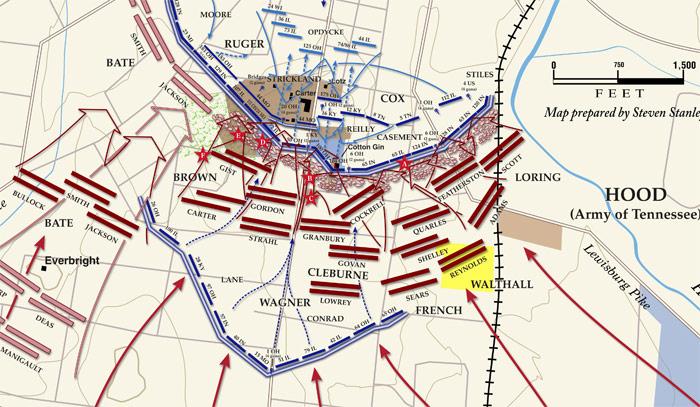

Confederate Gen. John B. Hood aimed to destroy a Union force under Gen. John M. Schofield before it could reach another Union army in Nashville, Tennessee. Schofield reached Franklin and sought to buy time for his supply trains by forming a defensive line on the southern edge of town. Hood reached Franklin anxious to destroy the Union force before it could escape and launched an assault in what is officially called the Second Battle of Franklin, November 30, 1864.

Hood’s mighty charge consisted of 18 brigades—some 20,000 men—over two miles of open ground. Although sometimes called the "Pickett's Charge of the West" it was actually much larger and covered twice the distance. And unlike Pickett’s Charge, the Confederates did not retreat; they stubbornly held advanced positions until nightfall. According to participants, this was a struggle unlike any other and resulted in horrific losses on both sides. Confederates, sustained particularly high casualties--more than 6,000 of which 12 were suffered by generals. Six of these generals (Cleburne, Carter, Adams, Granbury, Gist, and Stahl) were killed or mortally wounded in the Civil War’s deadliest attack for general officers.

The Most Consequential Attack of the Civil War: Horatio Wright’s Breakthrough at Petersburg, April 2, 1865

Confederate General Robert E. Lee had been essentially trapped in his lines around Richmond and Petersburg for nine months by the time spring came in 1865. On March 25th, Lee launched a desperate assault with some 20,000 men against Union-held Fort Stedman. The attack failed and his men filed back into their lines. But Union Gen. U.S. Grant countered with probes along his lines and his troops succeeded in capturing Confederate picket lines. In the Battle of Jones Farm, Sixth Corps troops, under Gen. Horatio Wright, took a key picket line which brought them within one-half mile of the thinly held Confederate position.

On the early morning of April 2, 1865, Wright formed his more than 14,000 men into a wedge formation and charged the Confederate position, manned by only 2,800 soldiers. The attack plunged through abatis, over the breastworks and, after nearly ten months, the Union finally broke through the main Confederate line. So serious was the breakthrough that General Lee wired Richmond that he intended to evacuate Petersburg and Richmond that night. The Union occupied the abandoned cities the next day. While other assaults may have been more decisive, none other could claim the fall of the Confederate capital and with it the distinction of being the most consequential attack of the Civil War.

Related Facts

- None of the above attacks were failures. In no case did the attackers fall back en masse and in most cases they succeeded in driving the enemy. Apparently, launching enough soldiers in a coordinated effort worked.

- Large assaults didn’t always work, however. The number of sad, pointless or disastrous charges in the Civil War is too many to list: Cold Harbor, Atlanta, Fredericksburg, Kennesaw Mountain, the Crater, Malvern Hill, Fort Steadman, Bentonville and so many more.

- Although often painted as a defensive fighter, Confederate Gen. James Longstreet commanded some of the largest assaults of the Civil War at Second Manassas, Gettysburg, Chickamauga, and the Wilderness.

- At Gettysburg, Confederate assaults on July 1 (more than 20,000 charging in the afternoon) and July 2 (16,000 attacking en echelon) were each larger than Pickett’s Charge on July 3 (12,000).

- Perhaps the most impetuous large-scale assault of the war was the unplanned attack of Union Gen. George H. Thomas’ troops up the slopes of Missionary Ridge, November 25, 1863.

- At Parker’s Crossroads, Confederate Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest is known for ordering his troops to “Charge ‘em both ways.”

Learn More: Infantry Tactics

Related Battles

6,800

8,700

23,049

28,063