The Battles of Appomattox Station and Court House

Patrick Schroeder

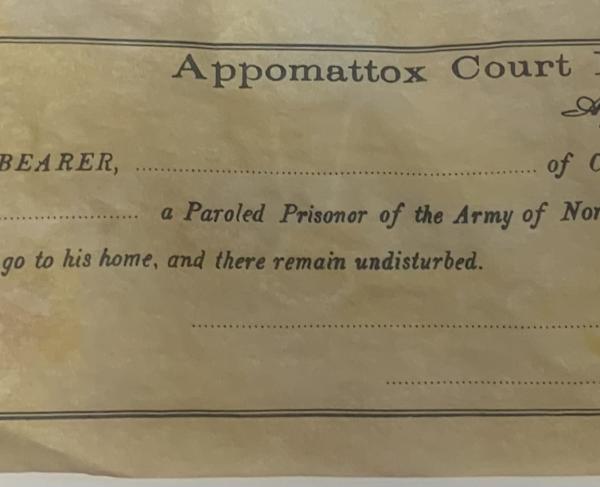

On the afternoon of April 8, 1865, four supply trains awaited Lee’s army at Appomattox Station. The news reached Federal Major General George A. Custer and he rapidly pushed his division forward with the 2nd New York Cavalry in the lead. These trains are loaded with supplies—clothes, blankets, equipment, ordnance, medical supplies, and most importantly—food. After moving along the wagon road beside the railroad, Custer’s men approach Appomattox Station from the southeast. The Station consisted of only a few houses with a squad of Confederate cavalry guarding the trains. Fred Blodgett (of the 2nd New York Cavalry) rode up to an engineer, calling out “Hands up,” while leveling his carbine. A call for engineers among Custer’s men went out in order to get the cars away as a large Confederate force was believed to be in the area, and shells began to rain down in the area of the Station.

These shells were fired by Confederate Brigadier General Rueben Lindsay Walker’s Reserve Artillery which had been advanced to the head of Lee’s column in order not to impede the movement of the Army of Northern Virginia. With Walker were approximately 100 cannon, 200 baggage wagons, and the army hospital wagons—all encamped, little expecting to encounter Federal forces. Walker’s men were preparing for supper, and Walker himself was seated on a stump being shaved by one of his men, when the cry went up “Yankees”, “Sheridan” and a short way off a mounted man crying “The Yankees are coming.”

A fourth train which had just arrived, started back for Lynchburg in such a rush that it broke some of the couplings and left most of its cars behind. Walker drew his men into a semi-circle and was supported by the only troops in the vicinity, Talcott’s Engineers (acting as infantry), General Martin Gary’s Cavalry Brigade (7th South Carolina, 7th Georgia, 24th Virginia), and 75 to 100 artillerymen acting as infantry. Encounters developed as Federal skirmishers pushed northeast from the Station.

The ground was not good for fighting a battle, mainly thick shrubbery and dense forest with some trails leading through it, and an unusual fight it would be—artillery against mounted cavalry. The Confederates were hampered be the unexpectedness of the attack, lack of organization, and no central command, which resulted in mass confusion. Custer’s men were not sure what lay ahead and were ordered by him to charge, but the advance became disjointed probes and pushes through the unfriendly terrain. Almer Montague of the 1st Vermont Cavalry commented “we found on entering the woods that the underbrush and vines were too thick for us to march through and keep our organization and we were soon advancing 'every man for himself'. Shells crashing through trees overhead.—But now and then our men were in their rear and up to the mouth of their guns, they poured out such a volley of grape and canister that it was impossible to resist and we were obliged to fall back. Again we rallied and advanced and again were repulsed by grape and canister.”

Martin’s battery fought aggressively on the Confederate left, continuously firing while boldly moving forward. Custer’s men made two or three probing assaults, none very anxious to get too close the walls of iron being thrown at them by the discharges of canister. Meanwhile, the Confederate batteries that were not engaged did their best to escape west towards Lynchburg or north towards Oakville. As darkness was coming on, a final concerted charge was made. A member of the 2nd New York Cavalry recalled that they made a charge down a narrow lane that led to an open field where the Confederate artillery was posted, and coming out of the woods, “A tornado of canister-shot swept over our heads, the next instant we were in the battery.” Montague of the 1st Vermont recalled, “Every man was fighting for himself and fighting like tigers.” He was hit by spent canister, paralyzing his leg for a time.

Some of the discharges of canister found their mark, taking down horses and men, one of them being a future Governor of Vermont, Charles J. Bell, with an iron ball lodged in the back of his hand. In the swirl of fighting, the color bearer of the Washington Artillery of New Orleans, William Davis, “A splendid soldier,” was killed staining the flag with his life blood. The flag was captured by Barney Sheilds of the 2nd West Virginia Cavalry. Also killed was Major Sesch Howe of the 1st West Virginia Cavalry. He was the fifth of five family members to die in the war.

As for casualties from this fight, there are no Confederate reports, so the exact total will never be know—perhaps 100 men killed and wounded in some manner, but nearly 1,000 Confederate soldiers captured, including Brigadier General Young Moody, and about 100 wagons. Federal casualties totaled less than 50, but Union surgeons commented that they “had never treated so many extreme cases in so short a fight. The wounds were chiefly made by artillery, and were serious; many patients being badly mangled."

As the fighting at Appomattox Station subsided, elements of the 15th New York Cavalry, under the direction of Lieutenant Colonel Augustus Root, leapt the fence and gained the Lynchburg-Richmond Stage Road and charged into the village of Appomattox Court House, capturing wagons and teamsters along the way. Jesse Hutchins of the 5th Alabama Battalion was killed in front of the Courthouse building. The cavalry circumvented the Courthouse and galloped towards the George Peers’ house. While passing the Rosser shops a member of the 5th Alabama Battalion put a bullet through Root’s neck, unhorsing him and killing him instantly, those following were met by a volley a line of troops formed in the vicinity of the Peers home.

The New Yorkers retreated back along the stage road, gathering prisoners and shooting mules as they went, thus concluding the engagements on April 8.

The Battle of Appomattox Station commenced shortly after 4 pm and lasted until dusk with varying intensity, although more fighting continued in the direction of Appomattox Court House until probably 9 pm. The success of Custer’s troopers on the evening of April 8, dispersing and capturing Walker’s artillery and securing the Richmond-Lynchburg Stage Road were vital—the Federals now held the high ground west of Appomattox Court House, squarely across Lee’s line of march. With Lee’s line of retreat blocked, his only options on April 9, 1865, was to attack or surrender. Lee elected to attack. He held a Council of War the night of April 8, and it was determined that an assault would be made to open the road, believing that only Federal cavalry blocked the way. However, during the night parts of three Federal Corps had made a forced march and were close at hand to support the Federal cavalry in the morning.

It was the action on April 8, 1865 (the Battle of Appomattox Station), that determined the surrender would take place on April 9th in the village of Appomattox Court House. The advantage of position gained by the action on April 8, gave the Federals control of the strategic ground necessary to force Lee’s surrender.

That night a Federal cavalry brigade under Brevet Brigadier General Charles Smith from General George Crook’s division occupied the ridge ¾ of a mile west of Appomattox Court House—building breast works of dirt and fence rails along the Oakville Road. The brigade consisted of the 1st Maine, 2nd New York Mounted Rifles, and the 6th and 13th Ohio. Smith moved Lieutenant James H. Lord’s two 3-inch Ordnance Rifles (cannon) forward, supported by skirmishers of the 1st Maine. Though foggy, Lord’s men began sending rounds into the Confederate camps with some effect—one shell striking John Ashby of the 12th Virginia Cavalry (now buried in the Confederate Cemetery).

Gordon formed his lines at the western edge of the village with the divisions of General Clement Evans on the left, General James Walker in the center, General Bryan Grimes on the right and General William Wallace’s division was in a second line. At the end of Tibbs lane was General Fitz Lee with the cavalry divisions of Generals Rooney Lee, Tom Rosser and Tom Munford. The infantry and cavalry were supported by General Armistead Long’s artillery.

At 7:50 am, the Confederates, in a left wheel motion, move forward—with the “usual rebel yell.” A veteran of the 1st North Carolina Sharp Shooters said he never saw one so “Magnificently executed as this.” Perhaps realizing the opportunity to secure the lightly supported guns of Lord’s battery and in the forefront of the wheel Roberts’ Brigade of the 4th and 7th North Carolina Cavalry drew sabers, charged and captured the cannon and some of Lord’s men. Despite the capture of his guns, Lord was cited for gallant and meritorious service and promoted to Major for his bold stand which delayed the Confederate advance.

Smith’s line was soon outflanked. Rooney Lee’s men stayed with the infantry wheel while Rosser and Munford pressed forward (west) hoping to get on the Federal flank and gain the Stage Road in their rear. Meanwhile, General George Crook directed General Ranald McKenzie’s small division of cavalry from the Army of the James, and a brigade under Colonel Samuel B. Young, to move up to support Smith on the left. They were met in turn by Rooney Lee’s Cavalry and likewise driven back, along with Smith. The Confederate infantry wheeled and opened the stage road and faced south while William Cox’s North Carolina brigade advanced along the stage road to the west.

Now, the Army of the James arrived on the field, led by Brigadier General Robert Foster’s division. Colonel Thomas Osborn’s Brigade advanced west along the stage road with the 62nd, 67th Ohio, 39th Illinois, 199th and 85th Pennsylvania Infantry, followed by Colonel George Dandy’s brigade which included the 11th Maine Infantry which moved to support the left flank of the 62nd—but not before the Confederates forces tore into the 62nd’s flank (losing over 50 men killed, wounded, and captured). The 11th Maine charged out of the woods and heading straight for the Confederate guns when it was attacked in the flank as well. The 11th Maine's Colonel John Hill went down wounded and was temporarily captured. In the charge the 11th was swept by canister, losing a regimental favorite—Moses Sherman—known as “Little Moustache.” The 11th Maine suffered over 60 casualties. Men of the 199th Pennsylvania captured a Confederate 20-pounder. As Confederate artillery fired from the ridge, a shell passed through the Coleman house mortally wounding a slave woman named Hannah Reynolds.

The weight of the Federal numbers began to tell as Brigadier General John Turner’s Division from the 24th Corps arrived on Foster's right flank as well as Colonel William Woodward's brigade of United States Colored Troops (25th Corps), filling a gap between the two divisions. A second brigade of United States Colored Troops under Colonel Ulysses Doubleday also arrived on the field. Confederate General Gordon, at some point that morning sent back a message: “Tell General Lee that my command has been fought to a frazzle and unless Longstreet can unite in the movement, or prevent these forces from coming upon my rear, I can not long go forward.”

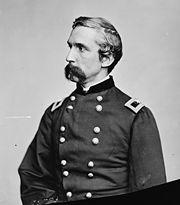

On the right of the Army of the James, from the south, came Major General Charles Griffin’s 5th Corps, slanting north at an angle across the fields toward Appomattox Court House, advancing through the Trent and Sears properties and encountering Confederate skirmishers. On the extreme right of the 5th Corps skirmish line is the 185th New York Infantry and 198th Pennsylvania Infantry commanded Brigadier General Joshua Chamberlain. Chamberlain’s men, under fire from batteries near the edge of the village (among them the Richmond Howitzers and the Salem Flying Artillery) advanced to the vicinity of the Mariah Wright house when a white flag approached. A small foray west of the village was made by 25 men of the 4th and 14th North Carolina Infantry as a delaying action, while the remainder of Gordon’s Corps retreated and reformed on the east side of the shallow Appomattox River.

As the 5th Corps advanced, Custer and Brigadier General Thomas Devin’s divisions moved behind it—east on the LeGrand Road—putting additional pressure on the Confederate left flank as the Confederate infantry withdrew through the village. After a white flag had appeared on Custer’s front, General Martin Gary’s cavalry brigade disavowed the truce and attacks Custer’s advance, but the attack was quickly beaten back, suffering losses.

Some brief skirmishing occurred about two miles west of Appomattox Court House near the Widow Robertson’s where some of Munford’s Confederate cavalry regained the stage road and engaged Federal troopers under Brigadier General Henry Davies, now supported by McKenzie and Young. After some brief clashes the Confederate cavalry which found itself outside the tightening noose, headed for Lynchburg.

In the rear of Lee’s army lay the bulk of the Federal Army of the Potomac—more than 30,000 men of the 2nd and 6th Corps. Lee was effectively surrounded, he was “check-mated.” The horrific final battle that many feared did not come to pass as the advantage of position gained in the action on April 8, combined with further movements on April 9, gave Grant’s forces control of the strategic ground necessary to force Lee’s surrender. Casualties of these two battles have been estimated at approximately 500 total killed and wounded (possibly higher), and over 1,000 men captured in the two days’ of fighting.

Patrick Schroeder was born at Fort Belvoir, VA, and raised in Utica, NY. He attended Stuarts Draft High School, Augusta County, VA. and graduated Cum Laude with a B.S. in Historical Park Administration from Shepherd College, Shepherdstown, WV. He holds an M.A in History from Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, VA. Patrick began work as a Living History Interpreter at Appomattox Court House National Historical Park in 1986 and worked at Red Hill, the Patrick Henry National Memorial, from 1994-1999. He became the park “Historian” at Appomattox Court House National Historical Park in January 2002. He has written or edited and published 16 Civil War titles, including Thirty Myths About Lee’s Surrender, More Myths About Lee’s Surrender, The Confederate Cemetery at Appomattox, and Recollections and Reminiscences of Old Appomattox and Its People.

Related Battles

152

500

121

1,000