The Destruction of the Albemarle

By William B. Cushing

In September, 1864, the Government was laboring under much anxiety in regard to the condition of affairs in the sounds of North Carolina. Some months previous (April 19th) a rebel iron-clad had made her appearance, attacking and recapturing Plymouth, beating our fleet, and sinking the Southfield. Some time after (May 5th), this iron-clad, the Albemarle, had steamed out into the open sound and engaged seven of our steamers, doing much damage and suffering little. The Sassacus had attempted to run her down, but had failed, and had had her boiler exploded.

The Government had no iron-clad that could cross Hatteras bar and enter the sounds, and it was impossible for any number of our vessels to injure the ram at Plymouth.

At this stage of affairs Admiral S. P. Lee spoke to me of the case, when I proposed a plan for her capture or destruction. I submitted in writing two plans. The first was based upon the fact that through a thick swamp the ironclad might be approached to within a few hundred yards, whence India-rubber boats, to be inflated and carried upon men's backs, might transport a boarding-party of a hundred men; in the second plan the offensive force was to be conveyed in two very small low-pressure steamers, each armed with a torpedo and a howitzer. In the latter (which had my preference), I intended that one boat should dash in, while the other stood by to throw canister and renew the attempt if the first should fail. It would also be useful to pick up our men if the attacking boat were disabled. Admiral Lee believed that the plan was a good one, and ordered me to Washington to submit it to the Secretary of the Navy. Mr. Fox, Assistant Secretary of the Navy, doubted the merit of the project, but concluded to order me to New York to "purchase suitable vessels." Finding some boats building for picket duty, I proceeded to fit them out. They were open launches, about thirty feet in length, with small engines, and propelled by a screw. A 12-pounder howitzer was fitted to the bow of each, and a boom was rigged out, some fourteen feet in length, swinging by a goose-neck hinge to the bluff of the bow.

A topping lift, carried to a stanchion inboard, raised or lowered it, and the torpedo was fitted into an iron slide at the end. This was intended to be detached from the boom by means of a heel-jigger leading inboard, and to be exploded by another line, connecting with a pin, which held a grape shot over a nipple and cap. The torpedo was the invention of Engineer Lay of the navy, and was introduced by Chief-Engineer Wood. Everything being completed, we started to the southward, taking the boats through the canals to Chesapeake Bay. My best boat having been lost in going down to Norfolk, I proceeded with the other through the Chesapeake and Albemarle canal.

Half-way through, the canal was filled up, but finding a small creek that emptied into it below the obstruction, I endeavored to feel my way through.

Encountering a mill-dam, we waited for high water, and ran the launch over it; below she grounded, but I got a flat-boat, and, taking out gun and coal, succeeded in two days in getting her through. Passing with but seven men through the canal, where for thirty miles there was no guard or Union inhabitant, I reached the sound, and ran before a gale of wind to Roanoke Island.

In the middle of the night I steamed off into the darkness, and in the morning was out of sight. Fifty miles up the sound I found the fleet anchored off the mouth of the river, and awaiting the ram's appearance. Here, for the first time, I disclosed to my officers and men our object, and told them that they were at liberty to go or not, as they pleased. These, seven in number, all volunteered. One of them, Mr. Howarth of the Monticello, had been with me repeatedly in expeditions of peril.

The Roanoke River is a stream averaging 150 yards in width, and quite deep. Eight miles from the mouth was the town of Plymouth, where the ram was moored. Several thousand soldiers occupied town and forts, and held both banks of the stream. A mile below the ram was the wreck of the Southfield, with hurricane deck above water, and on this a guard was stationed. Thus it seemed impossible to attack with hope of success.

Impossibilities are for the timid: we determined to over come all obstacles. On the night of the 27th of October we entered the river, taking in tow a small cutter with a few men, whose duty was to dash aboard the wreck of the Southfield at the first hail, and prevent a rocket from being ignited.

We passed within thirty feet of the pickets without discovery, and neared the vessel. I now thought that it might be better to board her, and "take her alive," having in the two boats twenty men well armed with revolvers, cutlasses, and hand-grenades. To be sure, there were ten times our number on the ship and thousands near by; but a surprise is everything, and I thought if her fasts were cut at the instant of boarding, we might overcome those on board, take her into the stream, and use her iron sides to protect us afterward from the forts. Knowing the town, I concluded to land at the lower wharf, creep around, and suddenly dash aboard from the bank ; but just as I was sheering in close to the wharf, a hail came, sharp and quick, from the iron-clad, and in an instant was repeated. I at once directed the cutter to cast off, and go down to capture the guard left in our rear, and, ordering all steam, went at the dark mountain of iron in front of us. A heavy fire was at once opened upon us, not only from the ship, but from men stationed on the shore. This did not disable us and we neared them rapidly. A large fire now blazed , upon the bank, and by its light I discovered the unfortunate fact that there was a circle of logs around the Albemarle, boomed well out from her side, with the ver y intention of preventing the action of torpedoes. To examine them more closely, I ran alongside until amidships, received the enemy's fire, and sheered off for the purpose of turning, a hundred yards away, and going at the booms squarely, at right angles, trusting to their having been long enough in the water to have become slimy - in which case my boat, under full headway, would bump up against them and slip over into the pen with the r am. This was my only chance of success, and once over the obstruction my boat would never get out again. As I turned, the whole back of my coat was torn out by buckshot and the sole of my shoe was carried away. The fire was very severe.

In a lull of the firing, the captain demanding what boat it was. All my men gave comical answers, and mine was a dose of canister from the howitzer. In another instant we had struck the logs and were over, with headway nearly gone, slowly forging up under the enemy's quarter-port. Ten feet from us the muzzle of a rifle gun looked into our faces, and every word of command on boar d was distinctly heard.

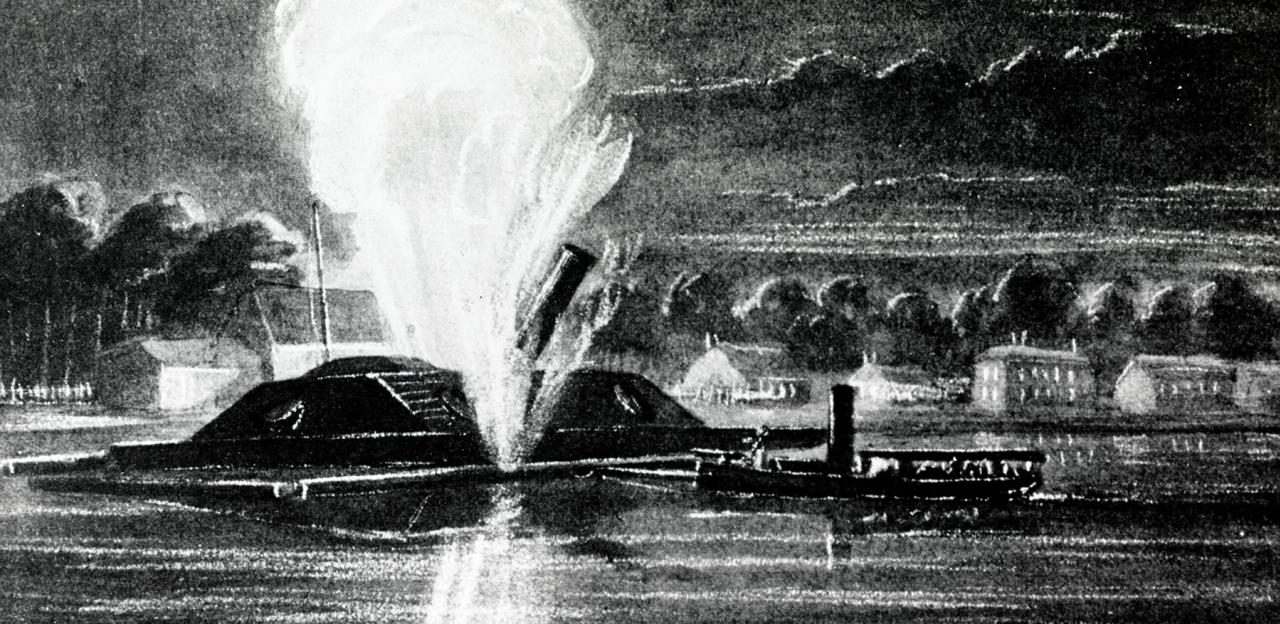

My clothing was perforated with bullets as I stood in the bow, the heel-jigger in my right hand and the exploding-line in the left. We were near enough then, and I ordered the boom lowered until the forward motion of the launch carried the torpedo under the ram's overhang. A strong pull of the detaching-line, a moment's waiting for the torpedo to rise under the hull and, I hauled in the left hand, just cut by a bullet. The explosion took place at the same instant that 100 pounds of grape, at 10 feet range, crashed among us, and the dense mass of water thrown out by the torpedo came down with choking weight upon us.

Twice refusing to surrender; I commanded the men to save themselves; and, throwing off sword, revolver, shoes, and coat, struck out from my disabled and sinking boat into the river. It was cold, long after the frosts, and the water chilled the blood, while the whole surface of the stream was plowed up by grape and musketry, and my nearest friends, the fleet, were twelve miles away; but anything was better than to fall into rebel hands, so I swam for the opposite shore. As I neared it a man [Samuel Higgins; fireman]; one of my crew, gave a gr eat gurgling yell and went down.

The rebels were out in boats, picking up my men; and one of the boats, attracted by the sound, pulled in my direction. I heard my own name mentioned, but was not seen. I now "struck out" down the stream, and was soon far enough away again to attempt landing. This time, as I struggled to reach the bank, I heard a groan in the river behind me, and, although very much exhausted, concluded to turn and give all the aid in my power to the officer or seaman who had bravely shared the danger with me.

Swimming in the night, with eye at the level of the water, one can have no idea of distance, and labors, as I did, under the discouraging thought that no headway is made. But if I were to drown that night, I had at least an opportunity of dying while struggling to aid another. Nearing the swimmer, it proved to be Acting Master's Mate Woodmanhe could swim no longer. Knocking his cap from his head, I used my right arm to sustain him, and ordered him to strike out. For ten minutes at least, I think, he managed to keep afloat, when, his physical force being completely gone, he sank like a stone.

Again alone upon the water, I directed my course toward the town side of the river, not making much headway, as my strokes were now very feeble, my clothes being soaked and heavy, and little chop-seas splashing with choking persistence into my mouth every time I gasped for breath. Still, there was a determination not to sink, a will not to give up ; and I kept up a sort of mechanical motion long after my bodily force was in fact expended.

At last, and not a moment too soon, I touched the soft mud, and in the excitement of the first shock I half raised my body and made one step forward; then fell, and remained halt in the mud and half' in the water until daylight, unable even to crawl on hands and knees, nearly frozen, with my brain in a whirl, but with one thing strong in me-the fixed determination to escape.

As day dawned I found myself in a point of swamp that enters the suburbs of Plymouth, and not forty yards from one of the forts. The sun came out bright and warm, proving a most cheering visitant, and giving me back a good portion of the strength of which I had been deprived before. Its light showed me the town swarming with soldiers and sailors, who moved about excitedly, as if angry at some sudden shock. It was a source of satisfaction to me to know that I had pulled the wire that set all these figures moving, but as I had no desire of being discovered my first object was to get into a dry fringe of rushes that edged the swamp; but to do this required me to pass over thirty or forty feet of open ground, right under the eye of a sentinel who walked the parapet.

Watching until he turned for a moment, I made a dash to cross the space, but was only half-way over when he again turned, and forced me to drop down right between two paths, and almost entirely unshielded. Perhaps I was unobserved because of the mud that covered me and made me blend with the earth; at all events the soldier continued his tramp for some time while I, flat on my back, lay awaiting another chance for action. Soon a party of four men came down the path at my right, two of them being officers, and passed so close to me as almost to tread upon my arm. They were conversing upon the events of the previous night, and were wondering " how it was done," entirely unaware of the presence of one who could give them the information. This proved to me the necessity of regaining the swamp sinking my heels and elbows into the earth and forcing my body, inch by inch, toward it. For five hours then, with bare feet, head, and hands, I made my way where I venture to say none ever did before, until I came at last to a clear place, where I might rest upon solid ground. The cypress swamp was a network of thorns and briers that cut into the flesh at every step like knives frequently, when the soft mire would not bear my weight, I was forced to throw my body upon it at length, and haul myself along by the arms. Hands and feet were raw when I reached the clearing, and yet my difficulties were but commenced. A working-party of soldiers was in the opening, engaged in sinking some schooners in the river to obstruct the channel. I passed twenty yards in their rear through a corn furrow, and gained some woods below. Here I encountered a negro, and after serving out to him twenty dollars in greenbacks and some texts of Scripture (two powerful arguments with an old darkey), I had confidence enough in his fidelity to send him into town for news of the ram.

When be returned, and there was no longer doubt that she had gone down, I went on again, and plunged into a swamp so thick that I had only the sun for a guide and could not see ten feet in advance. About 2 o'clock in the afternoon I came out fr on the dense mass of reeds upon the bank of one of the deep, narrow streams that abound there, and right opposite to the only road in the vicinity. It seemed providential, for, thirty yards above or below, I never should have seen the road, and might have struggled on until, worn out and starved, I should find a never-to-be-discovered grave. As it was, my fortune had led me to where a picket party of seven soldiers were posted, having a little flat-bottomed, square-ended skiff toggled to the root of a cypress-tree that squirmed like a snake in the inky water. Watching them until they went back a few yards to eat, I crept into the stream and swam over, keeping the big tree between myself and them, and making for the skiff. Gaining the bank, I quietly cast loose the boat and floated behind it some thirty yards around the first bend, where I got in and paddled away as only a man could whose liberty was at stake.

Hour after hour I paddled, never ceasing for a moment first on one side, then on the other, while sunshine passed into twilight and that was swallowed up in thick darkness only relieved by the few faint star rays that penetrated the heavy swamp curtain on either side. At last I reached the mouth of the Roanoke, and found the open sound before me. My frail boat could not have lived in the ordinary sea there, but it chanced to be very calm, leaving only a slight swell, which was, however, sufficient to influence my boat, so that I was forced to paddle all upon one side to keep her on the intended course.

After steering by a star for perhaps two hours for where I thought the fleet might be, I at length discovered one of the vessels, and after a long time got within hail. My "ship ahoy!" was given with the last of my strength, and I fell powerless, with a splash, into the water in the bottom of my boat, and awaited results. I had paddled every minute for ten successive hours, and for four my body had been "asleep," with the exception of my arms and brain. The picket-vessel, Valley City, upon hearing the hail, at once got under way, at the same time lowering boats and taking precaution against torpedoes. It was some tune before they would pick me up, being convinced that I was the rebel conductor of an infernal machine, and that Lieutenant Cushing had died the night before. At last I was on board, had imbibed a little brandy and water, and was on my way to the flag-ship.

As soon as it became returned, rockets were thrown up and all hands were called to cheer ship ; and when I announced success, all the commanding officers were summoned on board to deliberate upon a plan of attack. In the morning I was well again in every way, with the exception of hands and feet, and had the pleasure of exchanging shots with the batteries that I had inspected the day before. I was sent in the Valley City to report to Admiral Porter at Hampton Roads, and soon after Plymouth and the whole district of the Albemarle, deprived of the iron-clad's protection, fell an easy prey to Commander Macomb and our fleet.