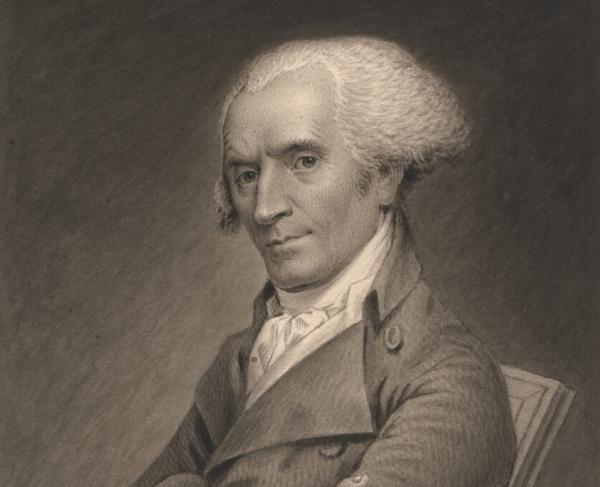

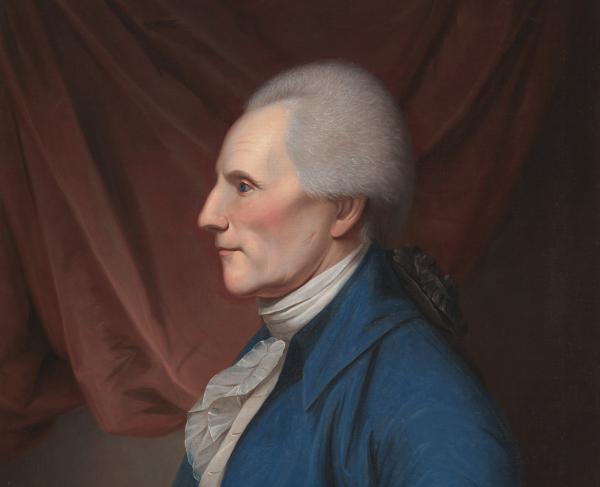

Lord North

As the Prime Minister of Great Britain during the Revolutionary War, Lord Frederick North grew up with great promise and a bright political future ahead of him. But his failure to suppress the rebellion in the American colonies, leading to their loss in 1783, gave him a reputation for incompetence that is still debated among historians today.

North was born on April 13th, 1732, and like most leading men of Britain, he grew up in a wealthy, aristocratic family. From his father’s side he could trace his ancestry to at least the 1400’s, and from his mother’s he claimed descent from Edward Montagu, the 1st Earl of Sandwich, a key figure in the Restoration of the Monarchy under King Charles II. As a student he attended the prestigious Eton School and later Trinity College, Oxford, graduating with a Master of Arts degree in 1750.

After an extended Grand Tour through Europe, a popular activity for young gentlemen of the time, North soon entered Parliament as a member of the House of Commons, and thanks to a combination of charm and personal connections, he joined the government as a junior Lord of the Treasury under the Duke of Newcastle in 1759. While in Parliament, North also married Anne Specke, daughter of a fellow MP, in 1756, and also established himself as independent from the many Whig Party factions that dominated Parliament, which eventually caught the attention of King George III, who favored North’s apparent Tory, or royalist, sympathies regarding the power of Royal Prerogative over Parliament. North succeeded Charles Townshend, namesake of the Townshend Acts, as Chancellor of the Exchequer, the equivalent to our Secretary of the Treasury, in 1766, and in 1770, became Prime Minister at the appointment of the King after his predecessor, the Duke of Grafton resigned for allowing rival power France to annex the Mediterranean island of Corsica. In fact, North inherited quite a few foreign policy crises from his predecessors to deal with early on in his Ministry. He couldn’t stop France from taking Corsica, but he did dissuade Spain from seizing the Falklands, a small British-held archipelago near the southern tip of South America. He also ably dealt with the enormous debt accrued from the previous Seven Years War, as well as made important reforms to the governance of Britain’s new colonies in South Asia and the profitability of the East India Company that ran them. Most uniquely, North enjoyed a highly productive relationship with his monarch, in an era when the exact extent of the powers of the British Crown had been a highly contentious topic. North’s deference to George’s royal prerogative was partly the reason why he was appointed Prime Minister in the first place, but he also ensured the Whigs in Commons, who supported Parliamentary Sovereignty, that the King was in no way overstepping his authority, preventing much internal strife. The American Revolutionary War, which took up most of his term in office, however, greatly overshadowed these and other important successes.

The Prime Minister was a leading voice in repealing the Townshend Acts, which placed taxes and duties on various goods imported to North America. At the instruction of King George, however, North did leave one tax in place, the one on tea that directly led to the famous Boston Tea Party of 1773. Decrying the act of vandalism and rebellion, North moved swiftly to punish the city of Boston itself through what Parliament called the Coercive Acts, known as the Intolerable Acts later in North America. North’s policies, therefore, directly pushed the colonists into open conflict with Parliament and the Crown, rather than cowing them into submission as he had hoped. Still, the Prime Minister remained resolute in dealing with the rebels with a firm hand, declaring to the Commons, “The Americans have tarred and feathered your subjects, burnt your ships, denied obedience to your laws and authority; yet so clement and so forbearing has our conduct been that it is encumbent [sic] on us now to take a different course…If they deny our authority in once instance, it goes to all. We must control them or submit to them.” Not much of a soldier and half a world away besides, North did little actually conduct the war effort personally, entrusting his generals and Secretary of State to the Colonies, George Germain, to put down the rebellion. At first, this seemed to be for the best, as only a few months after open conflict began at Lexington, the British smashed Washington’s army at Long Island and retook New York City. The American invasion of the Canadian provinces also faltered by this time. Congratulating North in a letter, King George predicted that “the rebell [sic] army will soon be dispersed.” Cause for celebration proved rather early, since Washington’s army survived well past their eviction from New York and British General John Burgoyne met defeat at the hands of Horatio Gates and Benedict Arnold at Saratoga, and when France, followed by Spain, entered the war on the Americans’ behalf, the tides began to turn, since unlike the colonists, these countries had advanced, professional militaries that could engage British forces across the globe. The addition of the Dutch Republic declaring war on Britain, as well as her traditional allies Portugal and Prussia joining the League of Armed Neutrality, proved too much to overcome for even as seasoned a statesman as North, though some do credit him with keeping ever-rebellious Ireland under control during the war. Part of doing so however meant reducing official discrimination against Roman Catholics through various acts of Parliament like the Papists Act of 1778, which later triggered a backlash in the form of the 1780 anti-Catholic Gordon Riots, leaving hundreds dead and many more homeless and impoverished.

After the British surrender to Washington at Yorktown, North argued that the fault lay in the military, not His Majesty’s government, but Parliament passed a motion of no confidence against him, and he resigned from office on March 20th, 1782. That did not spell the end of his political career. Almost a year to the day after his resignation, Lord North rejoined the government of William Cavendish-Bentinck, Duke of Portland as Home Secretary, but the real power in the ministry was an alliance between himself and Charles James Fox, once a fierce rival to both North and the King, as Foreign Secretary. Together, the Fox-North Coalition brought an end to the Revolutionary War by negotiating and signing the Treaty of Paris in 1783 but did not last long after that. The alliance was naturally tenuous and highly unpopular with the general public, which gave King George an opportunity to dissolve the government and select in their stead as Prime Minister the fresh-faced William Pitt the Younger, who dominated British politics for the next two decades.

Despite ultimately losing the war, North still held some hope of wielding some political influence in a future government, but ultimately retired from public life in 1786 on account of his failing eyesight. He passed away on August 5th, 1792 in London, survived by his wife and six children.