Santa Fe County and San Miguel County, NM | Mar 26 - 28, 1862

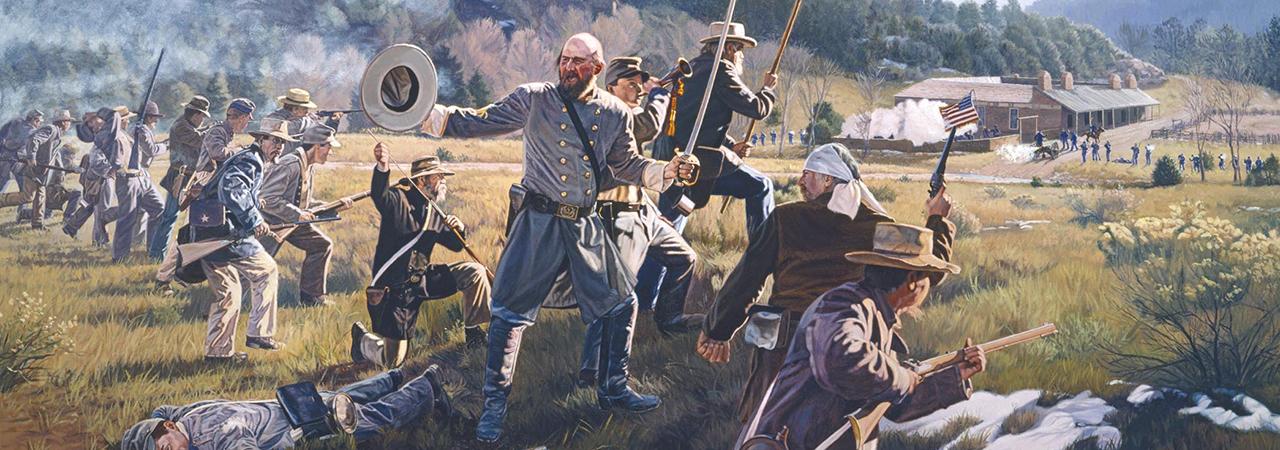

In the spring of 1862, Federal forces under the command of John P. Slough attacked and defeated a Confederate force near Glorieta Pass, New Mexico, ending a Southern invasion.

How It Ended

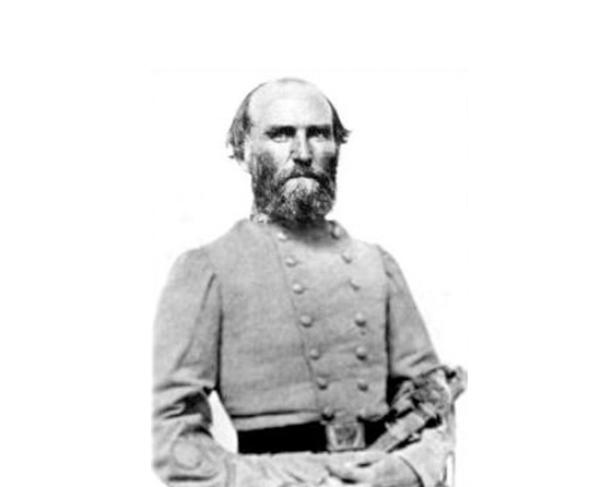

Union Victory. After spotting a Federal column heading his way, Col. William R. Scurry formed a battle line near Glorieta Pass. Once the two sides met, Scurry’s larger force quickly defeated the Federal column, pushing them out of the Pass. However, the victory was cut short when Federal forces destroyed their supply wagons, forcing them to retreat.

In Context

During the early spring of 1862, Confederate forces, under the command of Gen. Henry H. Sibley, established control over the New Mexico territory. Sibley moved north up the Rio Grande River towards Union-held Fort Craig. After failing to take the fort, Sibley moved further up the river towards Albuquerque, where he decided to capture Fort Union several miles to the east. In March of 1862, Sibley sent 200-300 men under the command of Maj. Charles L. Pyron to seize Glorieta Pass, which would provide the army a route to Fort Union.

After defeating a Federal force in the Battle of Valverde on February 20-21, 1862, the Confederate army moved north and entered Albuquerque on March 2nd, only to find that Union forces had removed or destroyed almost all the military supplies there. Nevertheless, Gen. Henry H. Sibley established his headquarters in the city and sent an advance party to occupy Santa Fe to secure additional supplies.

The Confederates accumulated about forty days’ worth of supplies through purchase or confiscation in Santa Fe, which Sibley considered adequate to continue his advance toward Fort Union. His vanguard, commanded by Maj. Charles L. Pyron was already on the Santa Fe Trail towards the fort. To bolster his numbers, Sibley sent the bulk of his brigade, commanded by Lt. Col. William R. Scurry, to the east side of the Sandia Mountains near Albuquerque in preparation for the advance. On March 12th, approximately 1,000 men with an accompanying artillery and wagon train began moving toward the Santa Fe Trail, some twelve miles east of the capital, while Sibley remained in Albuquerque.

Soon Pyron heard rumors from civilian travelers along the Santa Fe Trail that a Union force was advancing toward him. An aggressive commander, he left the town early on the morning of March 25th and marched to meet his oncoming enemies in the mountains southeast of Santa Fe. By nightfall, Pyron camped near Johnson’s Ranch. This unknown Federal force was commanded by Col. John P. Slough and poised to attack Sibley’s army from the north coming from Colorado.

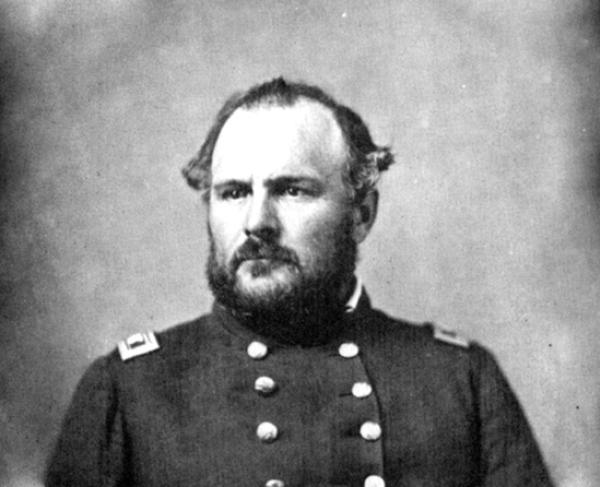

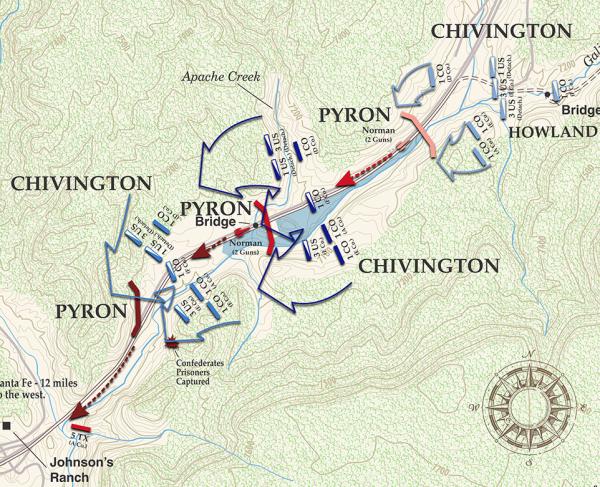

With approximately 404 men, John M. Chivington's Union column left their camp at Kozlowski's Ranch on the morning of the 26th. After marching five miles, the Union vanguard passed Pigeon's Ranch, another major way station on the Santa Fe Trail, then crested Glorieta Pass and descended into the eastern reaches of Apache Canyon. At the same time, Pyron halted less than two miles ahead, on an open, flat shelf north of Galisteo Creek. Many Texans who had not slept during the cold night immediately fell asleep while their commander sent a small party ahead to locate the Federals.

Around a sharp bend in the road came Chivington's advance party captured the Confederates. The Confederates withdrew with Chivington’s force in pursuit at about 2:30 p.m. The Union line halted in and across the road as a Confederate battle line quickly appeared on the open shelf. Chivington's infantry outflanked the Confederate line, but his cavalry failed to charge the wavering enemy. Pyron withdrew to another defensive position a mile or so west of Apache Creek: an insignificant dry gully spanned by a short, wooden bridge. The Confederate commander awaited an attack with his two artillery pieces near the Santa Fe Trail and his dismounted troopers across the valley floor and up the mountainsides north and south of Galisteo Creek.

This time Chivington's tactic worked perfectly. After successfully turning the Confederate flank, their artillery limbered up and retreated west to Pyron's camp at Johnson's Ranch. In the aftermath, the Federals captured 71 Texans, the most significant loss of Southern soldiers during the New Mexico Campaign. The fighting lasted until about 4:00 p.m., with equal casualties on both sides. Then, at dusk, Chivington withdrew to Pigeon's Ranch while the main Federal column approached Kozlowski's Ranch.

During the night of March 26–27, both commanders sent word of their fight back to their main columns. Confederate commander Lt. Col. William R. Scurry and Union commander Col. John Slough hurried to concentrate their forces for renewed battle the next day. No attack came, so the Texans fortified their Johnson's Ranch camp with earthen embankments while the Federals continued their concentration at Kozlowski's Ranch.

On the morning of March 28th, Scurry left one cannon and a handful of men to guard his supplies and field hospital, hoping that the bulk of his force, roughly 1,300 men, could defeat his enemy and continue to Fort Union and its vital supplies.

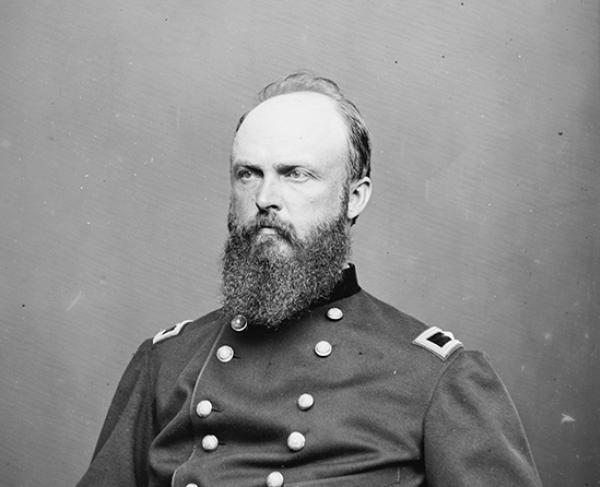

Shortly before 9:00 a.m, Slough broke camp and marched west along the Santa Fe Trail, intending to obstruct the movement of and cut off the supplies of the Confederate force threatening Fort Union. His tactical plan was, however, more complex. He directed Chivington to take a 500-man party of regular and volunteer infantry across Glorieta Mesa, south of the Santa Fe Trail, and march west to a point above Johnson's Ranch. Meanwhile, Slough would lead the remaining 800 soldiers along the road, confronting the Confederates in their camp while Chivington descended on the Texan flank in a coordinated attack. It was a standard Napoleonic plan dependent on Scurry's force being still encamped at Johnson's Ranch; however, Scurry was not at the Ranch.

Instead, as Chivington's flanking party left the road and the main column paused to further organize at Pigeon's Ranch, the advance pickets of each force encountered one another along the Santa Fe Trail. The Confederate infantry, followed by dismounted horsemen and artillery, quickly pushed back a small Union artillery and cavalry force sent ahead of the main force. Slough and his second-in-command Lt. Col. Samuel F. Tappan, responded by strengthening the center of a new Union defensive line. The opponents opened a furious fire in these positions for some three hours. Finally, the Texans, outnumbering the Federals by about 1,300 to 800, gradually outflanked the Union line.

Realizing the strength of his foe, Slough dispatched a messenger to find Chivington's flanking party. He also withdrew from the positions west of Pigeon's Ranch and formed a new defensive line north and south of the road through the ranch buildings and corrals, with artillery in the center. Scurry also used this time to reorganize his force, planning a coordinated, three-pronged assault on the new Federal line. By 2:00 p.m. he attacked, the southern and northern flanking parties failing to break the Union lines. However, Scurry led two ferocious assaults on the center, both blown apart by the concentrated Federal artillery and infantry fire. Two hours later, Maj. Pyron and a third charge against the enemy center succeeded, causing Slough to abandon his positions around Pigeon's Ranch and fall back down the Santa Fe Trail.

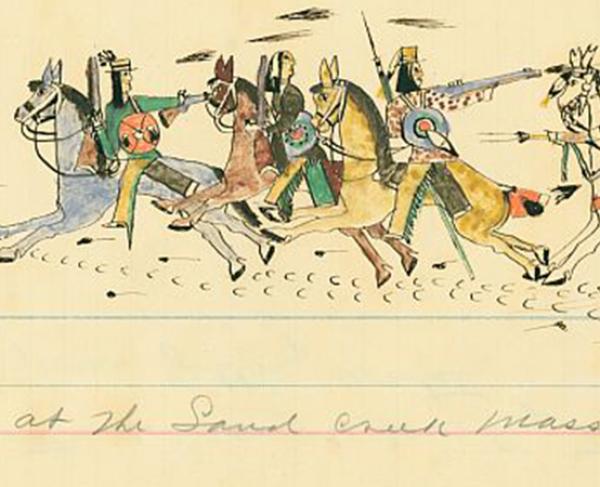

While fighting raged around Pigeon's Ranch, Chivington's flanking party descended on the Confederate camp, and the Union column captured cannons and soldiers before burning 80 supply wagons.

147

222

After nightfall, Confederate commander Lt. Col. William R. Scurry realized he had won the battle and was ready to pursue his defeated foe towards Fort Union. However, word reached Scurry that a Union flanking column had destroyed his wagon train. With this news, Scurry was forced to relinquish his gains and retreat to Albuquerque, ending the Battle of Glorieta Pass.

Food was scarce in New Mexico Territory. Though Scurry won the battle, his vital supply wagons were destroyed by a Union flanking column, thus forcing him to retreat towards Albuquerque.

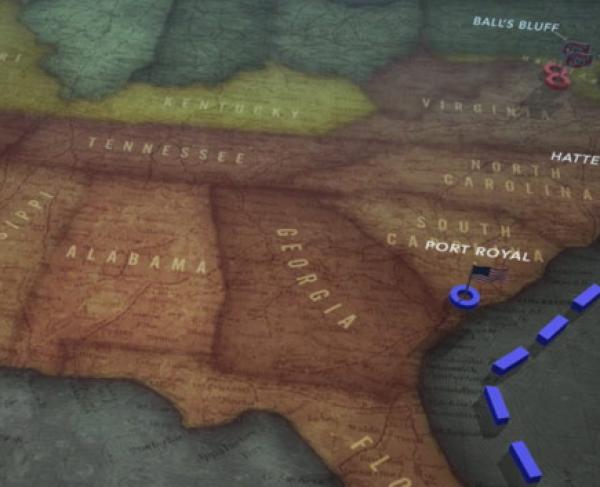

Glorieta Pass was situated along the Santa Fe Trail and linked Fort Union to Albuquerque and Santa Fe. Both Confederate and Union forces wished to control this route to bring supplies and soldiers through the region, which resulted in the battle. Ultimately, the Union took control over it, forcing the Confederate army to retreat to their base in Albequerque. Glorieta Pass would remain in Union hands for the rest of the war.

Glorieta Pass: Featured Resources

All battles of the Sibley's New Mexico Campaign

Related Battles

1,300

1,340

147

222