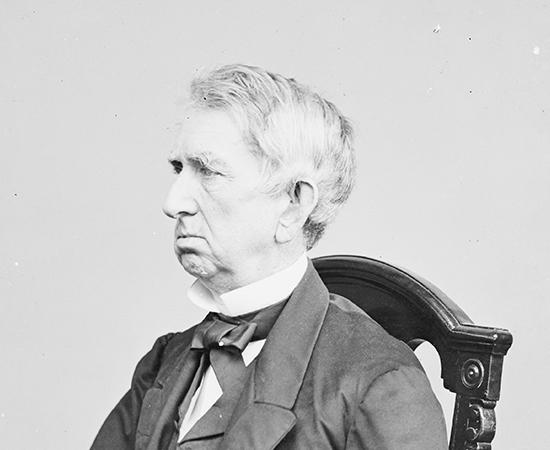

William H. Seward and the Emancipation Proclamation

By Allison Hinman, Interpreter and Research Assistant at the Seward House

William H. Seward risked his extensive political career on his conviction that all men should be free. As Governor of New York State, Seward made sure that fugitive slaves were guaranteed a trial by jury, which was passed by New York State legislature. In 1846 he defended a free black, William Freeman, who murdered four members of the Van Nest Family. Seward took on the case because he believed that Freeman was insane and concerned that Freeman would not receive a fair trial due to his race. During the trial Seward made several statements that supported the abolition movement, but one of his most powerful statements in his defense was:

"You, gentlemen, have or ought to have, lifted up your souls above the bondage of prejudices so narrow and mean as these. The color of the prisoner’s skin, and the form of his features, are not impressed upon the spiritual, immortal mind which works beneath. In spite of human pride, he is still your brother, and mine, in form and color accepted and approved by his Father, and yours, and mine, and bears equality with us the proudest inheritance of our race—the image of our maker. Hold him to be a Man."

Seward was unable to prove Freeman innocent based on insanity, but supported various civil movements such as the abolition movement and mental health reform through his defense of Freeman.

In 1850 Seward made his “Higher Law” speech where he stated: “[…] there is a Higher Law than the Constitution.” This incendiary statement was to Seward’s successful argument that California should be admitted into the Union as a free state. Due to Seward’s compelling argument California entered as a free state. Though Seward publicly supported the abolition movement he risked his political career behind closed doors by harboring fugitive slaves in his Auburn home. Seward and his wife, Frances, allowed their home to be used as a stop on the Underground Railroad. Seward even wrote in a letter on November 18, 1855 to Frances that “[t]he underground railroad works wonderfully. Two passengers came here last night.”

In 1858 Seward made another public address about the issue of slavery. This speech became known as Seward’s “Irrepressible Conflict Speech.” Seward believed the slave system to be “intolerable, unjust, and inhuman. He also indicated that having slave states and free states was incompatible and that “it is an irrepressible conflict between opposing and enduring forces, and it means that the United States must and will, sooner or later, become either entirely a slaveholding nation, or entirely a free-labor nation.” He insisted that a decision must be made about slave states and free states “even at the cost of civil war.”

Due to Seward’s outspoken opinion about slavery it was no surprise that he signed the Emancipation Proclamation. Lincoln wrote the Proclamation and read it during a Cabinet meeting, “Seward approved of the tone and purpose, but thought the time was not opportune for issuing it.” He felt that it would look like a cry for help. Seward had always advocated for the freeing of all slaves, but with this proclamation he felt that “such a proclamation ought to be ‘borne on the bayonets of an advancing army, not dragged in the dust behind a retreating one.” Seward’s suggestion to wait until after a victory was adopted along with his other: that newly freedmen “abstain from all violence unless in necessary self-defense.”

When Lincoln read the revised draft to the Cabinet it allowed Seward one more opportunity to make a suggestion. Seward asked, "Would it not, however, make the proclamation more clear and decided, to leave out all reference to the act being sustained during the incumbency of the present President, and not merely say that the Government 'recognizes,' but that it will maintain the freedom it proclaims.".

Fellow Cabinet member Salmon P. Chase agreed with Seward and thought that “the suggestions of Governor Seward very judicious, and shall be glad to have them adopted.” Seward made one final request; that "in the passage relating to colonization, some language should be introduced to show that the colonization proposed was to be only with the consent of the colonists, and the consent of the States in which colonies might be attempted.

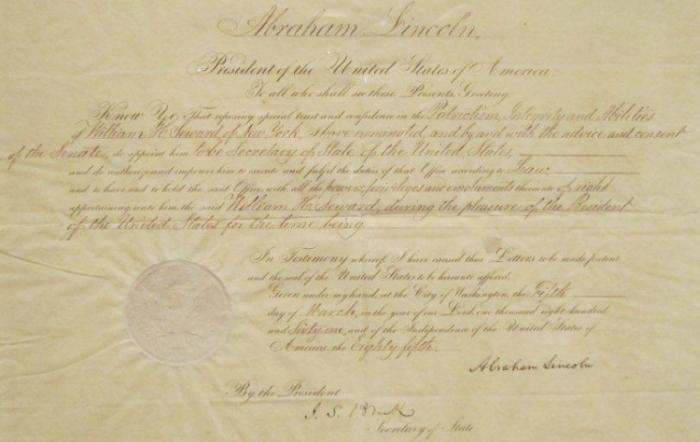

His final request was also adopted as part of the Emancipation Proclamation. The draft was approved by the Cabinet was “handed to Seward, who had it duly engrossed in official form, bearing the signature of the President and his own, with the great seal of the United States, and placed it on file in the Department of State.” In regard to the Proclamation Seward felt that “the interests of humanity have now become identified with the cause of our country.”

On January 1, 1863 Seward and his son, Fredrick, took the Emancipation Proclamation to the White House for signatures and authentication. Once the document was signed, copies were given to the press and the Proclamation was placed among archives. Seward wrote the following day that “The Proclamation of the President adds a new and important element to the war…[t]he very violence with which it will be met, probably will, after a little, increase its efficiency.” The signing of the Emancipation Proclamation was a significant moment in Seward’s career. After a lifetime of witnessing the injustices perpetrated by slavery and advocating for abolition, Seward had the satisfaction of seeing his dreams fulfilled.

Learn More: Civil War Leaders