Sailor's Creek

The Battle of Sailor's Creek

Sayler's Creek, Little Sailor's Creek, Marshall's Crossroads

Leaving Richmond behind in the aftermath of the Union Breakthrough at Petersburg, Confederate General Robert E. Lee hoped to link up with Joseph Johnston's army in North Carolina. First, however, Lee had to feed his beleaguered troops. After finding ordnance—but no food—at Amelia Court House, and discovering the road to Danville blocked by Federal entrenchments, Lee directed his army toward the supply depot at Farmville. Heading Lee's column were the First and Third Corps under the combined command of General James Longstreet, followed by General Richard Anderson's corps, and the Reserve Corps under General Richard Ewell, which was composed primarily of garrison units from the Confederate capital. The army's supply train followed with General John Gordon's Second Corps bringing up the rear. To evade the Union roadblock, Lee ordered a night march on April 5.

On the rainy morning of April 6, skirmish fire announced that General Andrew Humphreys' Union Second Corps was in pursuit. At the same time, General Philip Sheridan's cavalry rode parallel to Lee's line of retreat, launching hit-and-run strikes on the Rebel column. Anderson and Ewell's troops halted at Holt's Corner to fend off the Federal attackers and created a two-mile gap between Anderson and the nearest friendly unit. Into that gap Union General George Custer thrust his horsemen. Making matters worse Union General Horatio Wright's Sixth Corps was approaching from the east. With Yankee cavalry blocking the road to Farmville and infantry nipping at its heels, a sizable portion of Lee's army was caught in a vice.

After the alarm at Holt’s Corner, Gordon's corps and the supply train were diverted to the north in the hopes of joining the rest of the army. With the Union Second Corps in close pursuit, Gordon made a series of stands on high ground as the train withdrew. When supply wagons became bottle-necked at the Double Bridges over Sailor's Creek, the Federals got within striking distance. At around 5 PM, Humphreys’ attacked and the bulk of Gordon's force was driven to the opposite bank before darkness ended the fighting on this part of the field. Further to the south, Anderson and Ewell deployed on high ground between Little Sailor's Creek and Marshall's Crossroads. Ewell's divisions dug in facing northeast, toward the Hillsman farm. Extending the Confederate line to the south and west were two more divisions. The Confederate line was practically back-to-back and thus the disparate units were unable help one another.

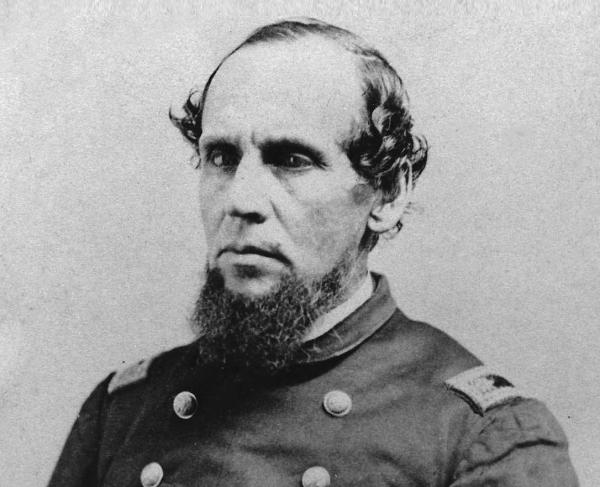

Wright's corps formed opposite Ewell and used twenty pieces of artillery to shell the Rebel force. Unfortunately Ewell had no operational artillery. After a thirty-minute cannonade, one of Wright’s divisions waded into the swollen waters of Little Sailor's Creek. Ewell's defenders let loose a volley that staggered a portion of the attacking force, which bolted for cover. Confederate General Stapleton Crutchfield seized this opportunity and led an impetuous counterattack spearheaded by his heavy artillery battalions. These artillerymen acting as infantry became embroiled in savage hand-to-hand combat that claimed Crutchfield’s life. By now more Federals had crossed the stream and were advancing on Ewell’s left. After another brutal melee, the Confederates began to surrender.

At Marshall's Crossroads, Anderson fared no better. General Wesley Merritt's Union cavalry pressed the Confederates on both flanks. Custer ordered a series of mounted assaults on General George Pickett's division while Union General George Crook's dismounted attacks put pressure on General Bushrod Johnson's men on the Confederate right. Custer's horsemen eventually broke through and Anderson's men began rushing for the rear or surrendering. Watching the battle from a distant knoll, Robert E. Lee was heard to exclaim, "My God! Has the army dissolved?"

That evening, Phil Sheridan reported his success to Grant saying, "If the thing is pressed I think that Lee will surrender." When word of this reached Abraham Lincoln, the president responded, "Let the thing be pressed."

April 6, 1865, came to be known as "Black Thursday" among the Confederates. In the three engagements along Sailor's Creek, Lee lost roughly one-fourth of his army, many of them captured. The Federals claimed 7,700 prisoners that day, including six generals, among them Ewell, Kershaw, and Robert E. Lee's eldest son, Custis. Lee wrote to President Jefferson Davis, "a few more Sailor's Creeks and it will all be over." Lee surrendered three days later.