Rufus Dawes at the Epicenter

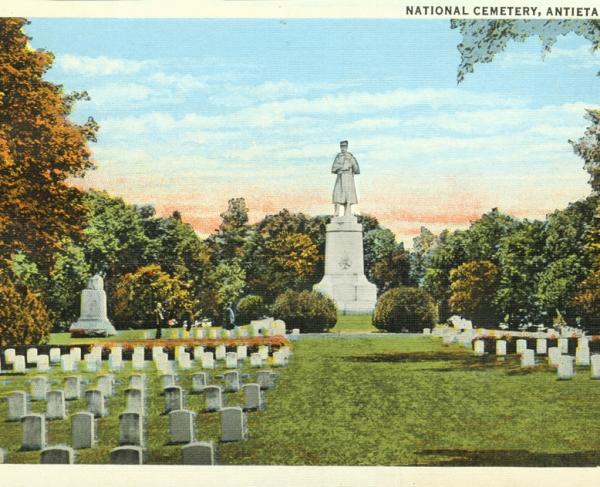

The Antietam Epicenter was crossed by nearly 30,000 men. Nearly 10,000 of those men were killed, wounded, or captured on this hallowed ground.

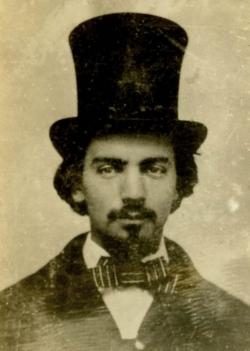

Rufus Dawes was a young man from a prominent Northern family. His grandfather, William Dawes, rode with Paul Revere to warn of the British advance through Middlesex County, Massachusetts, and his father was a wealthy merchant in Ohio. Rufus was 22, just graduated from college in Wisconsin, when Fort Sumter was bombarded on April 12, 1861.

Fearing that "someone would get ahead and crush the Rebellion before I got there," he began to raise a company only eleven days later. At the enlistment table, he tried to turn away an older man named John Kellogg, telling him that young single men should bear the brunt of whatever came next. Kellogg and many of his fellow family men could not be discouraged, however, and the “Lemonweir Minute Men” soon sputtered into being with Dawes and Kellogg in command, running rifle-less drills in front of a large audience of townsfolk on the common green. Dawes declared the company’s “readiness to answer any call to defend our country and sustain our government.”

The company was accepted into the Union Army as part of the 6th Wisconsin Volunteer Infantry. They soon became acquainted with the rigors and pains of official service. A German officer once stopped the company during regimental drill and dressed the men down, telling them “you looks just like von damn herd of goose.”

1861 passed mostly without incident, with the exception of an August skirmish with Confederate sympathizers outside of Baltimore. Nobody was seriously hurt in the nighttime firefight, but John Kellogg fell into a hole and “swore a blue streak” over the sound of gunfire. Dawes later remembered that “Kellogg was of quick blood and it was not always safe to congratulate him as the only man wounded in the Battle of Patterson Park.”

In August 1862, Dawes and his comrades fought their first major battle near Brawner Farm, Virginia. Moving through farmland around Gainesville, they were attacked on August 28 by 5,000 Confederate veterans led by Stonewall Jackson. The inexperienced Wisconsinites held their own alongside men from Indiana and New York, eventually repulsing the Rebels after what Jackson termed “a fierce and sanguinary struggle.” Dawes never forgot the sight of “the two crowds, they could hardly be called lines, standing within 50 yards of each other and pouring musketry into each other as fast as men could load and shoot.” This was the opening engagement of the Battle of Second Manassas, and Dawes and his comrades won great renown throughout the army for resisting Jackson’s assault.

Over the next two days, the battle developed into a stinging Union defeat. Nevertheless, a change of attitude swept through the Union army, and as the battle drew to a close the men did not repeat history—they stubbornly held their ground and withdrew in good order, feeling strongly that the “happiness of unborn millions and the future progress of the world” rested on their cause. It was a far cry from the first battle on that field, in which the Union men had fled disgracefully from the Confederates. This time, a year later, the Northern soldiers took pride in their conduct and scorned their officers, who had failed to match valor with capable leadership.

The air was literally charged with electricity. Rain, thunder, and lightning tore through the sky as the contending nations came to terms with the latest news from the front. The Confederate army had just repulsed two offensives aimed at its capital and the Southerners were confident but fatigued. Most in the North were astonished by the military failures thus far. President Abraham Lincoln, however, was putting the finishing touches on the Emancipation Proclamation. As the rains subsided, he yearned for an inspiring victory that would give him the credibility to issue such a momentous decree.

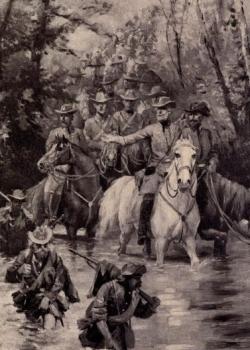

Robert E. Lee, meanwhile, was struggling to address the devastation that had come to his home state. Virginia civilians needed time to put a winter crop in the ground, wheat and greens, so that something could be harvested in spring. In order to give the farmers time to plant undisturbed, Lee decided to cross the Potomac and invade Maryland at the beginning of September, almost immediately after the Battle of Second Manassas. In wild dreams, he hoped to convince Maryland to secede. In his wildest dreams, he sought a Southern Saratoga, a triumph that would win recognition from Britain or France. He was also, of course, giving Lincoln an excellent opportunity to win a smashing victory on home soil. But sustaining the Confederacy required the taking of long chances.

Lee’s invasion fell apart. Many of his men refused to even cross the Potomac, claiming that they had signed on only to defend their homeland. The Marylanders he encountered were uninterested in secession. Food, clothing, and equipment began to give out—Major General James Longstreet himself did not have a complete pair of boots. So many men deserted the army that Major General A.P. Hill was motivated to declare that “only heroes are left.”

Lee’s fate was sealed when a secret copy of his campaign plan was discovered by Union soldiers after being left behind at a campsite near Monocacy Junction. Union General George McClellan waved the orders aloft and proclaimed that “here is a piece of paper with which if I cannot whip Bobby Lee, I shall be willing to go home!” The Union army, Dawes and his comrades among them, hurtled forward to destroy Lee’s unsuspecting forces.

On the hard march, Dawes encountered an old man standing by the roadside. “I have watched for you, I have prayed for you, and thank God you have come,” the old man shouted over and over as the column tramped past him. The spiritual advantages of defending home soil, so often enjoyed by the Confederates, permeated the Union army.

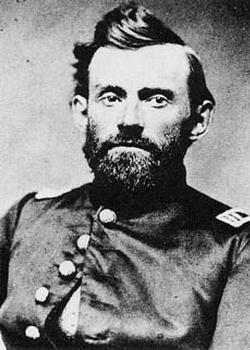

On September 14, Dawes and his comrades of the 6th Wisconsin, along with the other regiments (2nd Wisconsin, 19th Indiana, 7th Wisconsin) of his brigade, were ordered to advance up the steep slopes of South Mountain and attack a Rebel position at its crest. This was one of Lee’s blocking forces, a desperate guard for the Confederate army struggling to reassemble around the village of Sharpsburg, just ten miles further west.

General McClellan did not climb South Mountain personally, but rather stopped in the road upon his fine charger and pointed his sword dramatically at the smoke-ringed heights. Dawes led his men up the mountain and through a grueling battle, driving the Rebels from wooded ravines, out of fortified houses, and from behind high stone walls. Watching the scene, McClellan remarked that “those men must be made of iron,” giving birth to the popular nickname “The Iron Brigade.” When the heights were secured, Dawes and his men gave “three cheers for the Badger State.”

The Iron Brigade’s capture of Turner’s Gap opened a vital avenue for the Union army. Over the next two days, thousands of blue-clad soldiers poured over South Mountain and assembled for battle. Watching through field glasses from Sharpsburg, General Lee responded by forming a line behind Antietam Creek, unwilling to abandon his campaign without taking one chance at winning a major battle.

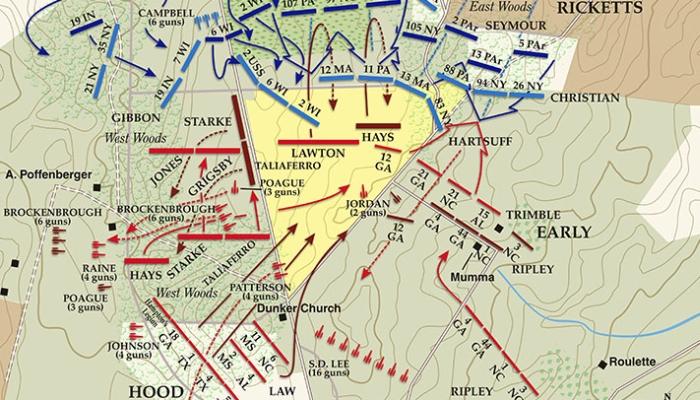

On the morning of September 17, Dawes and his comrades were cooking breakfast when they received the order to fall in and prepare for fighting. They knew that a big one was coming. The booming of muskets and cannons had been going on since before dawn. Dawes took his place as major, second-in-command of the 6th Wisconsin, and began to guide the battle line into action. A shell hissed overhead and the men looked about nervously. A second shell came in moments later, bursting directly above the regiment and tearing more than a dozen men to pieces within feet of Major Dawes. The Wisconsinites rushed forward, with Lieutenant John Kellogg directing a running firefight on the skirmish line and clearing a path for the rest of the regiment.

Roughly 400 men made up the 6th Wisconsin at this point in the war. Half of them, under Dawes, crashed into John Miller's cornfield, already winnowed by rifle fire; half under Colonel Edward Bragg stretched out of the corn and into the open ground around the Hagerstown Pike.

The regiment had advanced about 50 yards when they were suddenly caught in an explosive crossfire. It was as if a savage storm had broken in their very faces. The air hissed and crackled with Minie balls and shrapnel. Dawes ordered his men to lie down and conceal themselves among the cornstalks. Looking to his right, he could see Col. Bragg waving his sword wildly, trying to get his men out of the open and under cover of the fence that bordered the road.

Black powder smoke began to billow through the Cornfield, reducing visibility to mere yards. Union soldiers were charging in from all sides. Confederate batteries dropped shells indiscriminately into the exposed ground. “If shot and shell were rain, all would have gotten wet,” remembered one Iron Brigadier.

Dawes received word that Col. Bragg had an urgent message for him. Reaching Bragg’s position in the road, Dawes had to shout in order to be heard over the roar of battle. Bragg turned to him and put a hand on his shoulder. “Major, I am shot,” he said as he toppled into the dirt, blood pouring from his chest. The grizzled colonel had been hit in the first fire, but had gotten his men into cover before succumbing to the wound.

Command now fell to Major Dawes. He “felt great responsibility” at that moment. He was 23 years old. Taking up a rifle like a private soldier, he rested it across the fence and cut loose at the oncoming Rebels. The men passed him another rifle, and another, and another, until he had let off eight rapid shots into the crowd. John Kellogg guided the rest of the regiment out of the road and into the cover of the corn.

The road was full of dead and wounded men. One of them was Captain Werner Von Bachelle, an orphaned immigrant from France. His faithful Newfoundland dog, whom Bachelle had once taught to salute, sat over his master’s lifeless body. Dawes later reflected that the dog was probably Bachelle’s best friend in the world.

With no time to waste, Dawes ordered the regiment forward towards the southern edge of the cornfield. As the men reached the far fence, emerging from the corn, they were hit with a volley at point-blank range. Men did not just fall, Dawes said, they were “knocked out of the ranks by the dozens.”

The smoke and noise reached a fever pitch. Great gaps were torn in the Wisconsin line. From the rear surged the 14th New York Zouaves, fusing with the 6th Wisconsin and filling in the gaps indiscriminately. As if breasting a storm, this multi-hued fighting force crashed over and through the fence and charged into the Epicenter of battle.

“There is a rattling fusilade and loud cheers. ‘Forward" is the word.’ The men are loading and firing with demoniacal fury and shouting and laughing hysterically, and the whole field before us is covered with rebels fleeing for life, into the woods,” remembered Dawes of this moment.

“We push on over the open fields half way to the little church. The powder is bad, and the guns have become very dirty. It takes hard pounding to get the bullets down, and our firing is becoming slow. A long and steady line of rebel gray, unbroken by the fugitives who fly before us, comes sweeping down through the woods around the church. They raise the yell and fire. It is like a scythe running through our line.”

Dawes ran headlong into a counter-attack from John Bell Hood’s veteran division. Hood’s ragged Rebels charged and fired from their hips as they swept Union forces out of the Epicenter.

"It is a race for life that each man runs for the cornfield,” wrote Dawes. “A sharp cut, as of a switch, stings the calf of my leg as I run. Back to the corn, and back through the corn, the headlong flight continues. At the bottom of the hill, I took the blue color of the state of Wisconsin, and waving it, called a rally of Wisconsin men. 200 gathered.”

The regiment was reduced to 50% of its fighting strength. The Confederate counterattack was relentless. The two twelve-pounders of James Stewart’s Battery B, 4th US Artillery were a few rods away, firing wildly as the Rebels crowded closer. Brigadier General John Gibbon, commanding the Iron Brigade, his face black with powder, appeared in front of Dawes and, shouting to be heard, ordered him to advance to support the guns.

Gibbon dashed back to the battery as Dawes got his line moving. As the Wisconsinites approached, a huge BOOM and a shockwave rolled across the field. Gibbon had personally sighted a cannon and fired a double round of canister into the Rebels at point-blank range, sending fence rails flying through the air like a tornado. A huge cloud of smoke filled the area as the infantrymen pitched into the fray. Dawes thought his men were about to break when the 19th Indiana suddenly appeared, a surging line of blue sweeping through the corn and driving the Rebels away.

This was only the beginning of the fight for the Epicenter property. More Union men would come up, then more Confederates, then more Union, then more Confederates, then more Union, until finally the ground was firmly in Union hands. Later, the fighting would spread to the Sunken Road and Burnside Bridge, until more than 23,000 men had been shot down by their fellows.

Ultimately, the carnage would be deemed a Union victory. History would bear it out as one of the most significant victories of the war, allowing Lincoln to issue the Emancipation Proclamation and perhaps preventing the Confederacy from ever achieving foreign recognition.

On the battlefields of the Civil War, men young and old, Rufus Dawes and John Kellogg, were given the power to change the world. At Antietam, Dawes and his comrades poured their blood into the soil in service of future generations.

Rufus Dawes wanted badly for people to come to these fields and learn about the deeds and sacrifices that shaped his beloved nation. As an older man, visiting the graves of his comrades, he found “inspiration to stand for all they won in establishing our government on freedom, equality, justice, liberty, and protection to the humblest.”

Related Battles

12,401

10,316

2,325

2,685