Rocky Face Ridge

The Battle of Rocky Face Ridge

The dawn of 1864 brought renewed vigor to the Union war effort. The victories of 1863, a new overall Union commander, and the November presidential election looming on the horizon all blended together into an urgency heretofore unseen in the war.

In March, Ulysses S. Grant was promoted to command all Federal armies. Grant brought with him a mixture of experience and determination. Grant sought to apply pressure to the Confederate armies across all theaters of the war. While he wanted to remain in the Western Theater, it quickly became apparent the new overall general was desperately needed to right the Federal ship in the east. Thus, Grant turned the Military Division of Mississippi over to his most trusted subordinate, William T. Sherman.

The Confederates, too, felt an urgency. With the pending northern presidential election, there was a glimmer of hope that the Southern Confederacy could gain independence through the northern voters. If Lincoln were replaced with a northern “Peace Democrat,” independence for the South would almost be inevitable. But to win over the northern voters, the Confederate high command had to both survive the coming campaign season and make it so bloody that the voters of the north could not stomach the ever-growing casualty lists. The Federals held the initiative heading into the new campaign season, but defensive warfare could benefit the Rebels.

After the Confederate defeat at Chattanooga, Jefferson Davis relieved Braxton Bragg of command. Davis then reluctantly turned to Gen. Joseph E. Johnston. Johnston had amassed a long and relatively unimpressive resume during the war, yet the Confederate people and Southern soldiers felt a confidence in Johnston—a confidence Davis did not share. Johnston maneuvered his army into a blocking position in north Georgia. To the Confederates, the next logical Union step toward victory after the fall of Chattanooga was an offensive on the vital rail and supply center of Atlanta.

By the first week of May, Grant pressed his Federal armies into Virginia, Louisiana, and Georgia. On May 4, 1864, Sherman led 100,000 men—divided between three armies—into Georgia. While the capture of Atlanta was a goal of the spring offensive, the destruction of Johnston’s army was the higher priority. Without Confederate defenders, the Deep South was vulnerable to the Federal armies.

After pushing back brief resistance at Tunnel Hill on May 7, Sherman approached Johnston’s 60,000 Confederates entrenched west of Dalton, Georgia, along an imposing summit known locally as Rocky Face Ridge. The heights ran north-to-south for roughly ten miles and rose some seven hundred feet above the valley floor. After a winter of Confederate fortification, it was so covered with trenches, earthworks, and boulder traps that one Union soldier was moved to call it “the Georgian Gibraltar.”

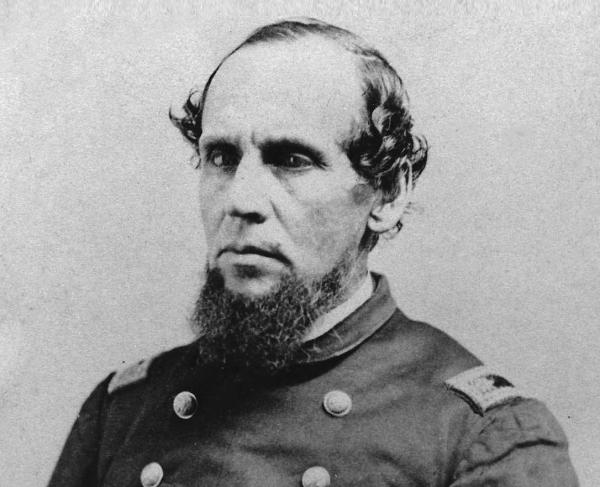

A head-on assault risked disaster. Instead, Sherman ordered Maj. Gen. James B. McPherson’s Army of the Tennessee to make a wide march around the southern tip of the ridge and strike the railhead at Resaca, Georgia, cutting the Confederate retreat and resupply line. Meantime, Maj. Gen. George Thomas’s Army of the Cumberland and Maj. Gen. John Schofield’s Army of the Ohio would launch diversionary attacks on the northern and western faces of the ridge to draw Johnston’s attention away from his vulnerable southern flank.

The fighting on Rocky Face Ridge began in earnest on May 8, with Union columns pressing towards Mill Creek Gap from the west and from Dug Gap to the south. Viewing the imposing heights of Rocky Face Ridge from Mill Creek. Hurling rocks when they ran out of ammunition, the Confederates held their position, but the Federals successfully kept Johnston’s men and his attention away from his southern sector.

On May 9, McPherson led the Union flankers through Snake Creek Gap 17 miles south and formed for an attack on Resaca. The Confederates here were vastly outnumbered—some 4,000 men versus McPherson’s 25,000—and the rest of the army was pinned down on the ridge. Still, their stubborn resistance cowed McPherson, and he refused to order the kind of full-scale attack that might have taken the town and broken Johnston’s supply line. Sherman was furious, but didn’t give up on the opportunity to cut off Johnston. On May 10, Sherman began to pull his men out of their lines opposing the Rocky Face, while Johnston matched Sherman’s maneuver, withdrawing into another fortified ring around Resaca where the fighting would continue.