Bombardment of Fort Sumter, Charleston Harbor: 12th & 13th of April, 1861.

Richard W Hatcher

In a message to Congress on December 5, 1815, President James Madison recommended that body provide “a liberal provision for the immediate extension and gradual completion of the works of defense…on our maritime frontier.” Congress complied, and construction began on a new series of coastal defenses that became known as the Third Coastal Defense System. Charleston Harbor was selected as a location for one of these new forts and, in 1829, a site was selected on a shoal at the harbor’s entrance beside the Main Shipping Channel, and about one mile west of Fort Moultrie. It was named Fort Sumter to honor Brig. Gen. Thomas Sumter, a hero of the South Carolina militia during the Revolutionary War.

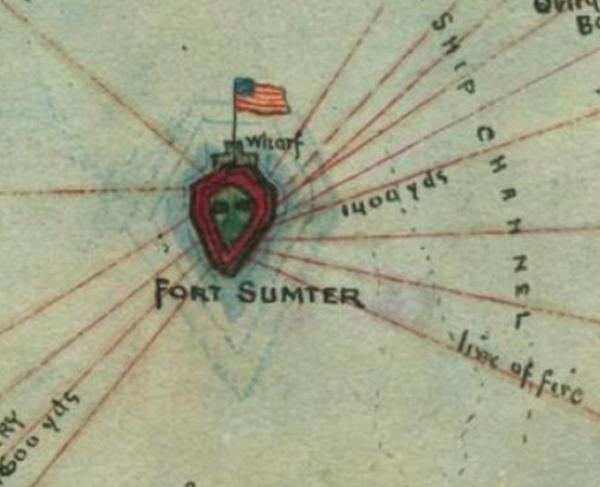

From 1829 to 1845, approximately 109,000 tons of rock and stone were used to create a 2.5-acre artificial island. Next, a pentagonal brick fort began to rise above the harbor’s waters. Fort Sumter was designed to mount 135 guns and provide living space for 650 officers and soldiers. The plan called for the four main walls to house three tiers of guns directed at the channel and the gorge wall to mount guns on the top tier. In December 1860, the fort was 90 percent complete, but construction stopped—never to be resumed—once South Carolina passed the Ordinance of Secession.

The previous month, Maj. Robert Anderson, First U.S. Artillery Regiment, had assumed command at Fort Moultrie on Sullivan’s Island. The 55-year-old Kentuckian and 1825 West Point graduate was a veteran of the Black Hawk, Second Seminole and Mexican Wars, as well as one of the Army’s top artillery officers. His command consisted of two companies of the First Artillery and the regimental band—a total of 84 officers and men.

Fort Moultrie was one of three active federal fortifications in Charleston Harbor, each with different challenges. Years of neglect had weakened Moultrie’s defensive capabilities; nearby terrain rose higher than the fort’s walls. Castle Pinckney, situated at the mouth of the Cooper River, was in good condition, but garrisoned only by an ordnance sergeant and his teenage daughter. The unfinished Fort Sumter was the most important of the three—a fact not lost on Anderson. In a December 9, 1860, report from Fort Moultrie, he wrote, “Fort Sumter is a tempting prize, the value of which is well known to the Charlestonians, and once in their possession, with its ammunition and armament and walls uninjured and garrisoned properly, it would set our Navy at defiance, compel me to abandon this work, and give them the perfect command of this harbor.”

Two days later, Maj. Don Carlos Buell delivered verbal instructions from Secretary of War John B. Floyd to Anderson, stating that “an attack on or attempt to take possession of any one of them [the forts] will be regarded as an act of hostility, and you may then put your command into either of them which you may deem most proper to increase its power of resistance.” Prompted by South Carolina’s secession on December 20, the commencement of state patrol boats operating between Forts Sumter and Moultrie, the size of his garrison and the growing threat of hostile action, Anderson transferred his command to Fort Sumter on the night of December 26, 1860.

In a message earlier that day to Adj. Gen. of the Secretary of War Samuel Cooper, Anderson wrote, “The step I have taken was, in my opinion, necessary to prevent the effusion of blood.” The next day he wrote to Floyd saying, “I abandoned Fort Moultrie because I was certain that if attacked my men must have been sacrificed, and the command of the harbor lost…the garrison never would have surrendered without a fight.” Despite Anderson’s desire to “prevent the effusion of blood” and avoid the sacrifice of his command, the chain of events that followed resulted in the commencement of overt hostilities four months later.

On December 27, Francis Pickens, the newly elected governor of South Carolina, demanded that Anderson return to Fort Moultrie. The major refused. Pickens also ordered the state militia to occupy Fort Moultrie, Castle Pinckney and the U.S. Arsenal, all of which occurred without incident. Then, South Carolina forces began building defensive works around the harbor. Some were directed at Fort Sumter, others on Morris and Sullivan’s Islands were directed to fire into the shipping channels. On James Island, the long-abandoned Fort Johnson was occupied and guns mounted. Simultaneously, inside Fort Sumter, Anderson’s command, aided by three Army Corps of Engineer officers and 40 civilian employees, began mounting cannon and improving the fort’s defenses.

Meanwhile, in Washington, D.C., President James Buchanan’s response to the growing crisis was to send the civilian ship, Star of the West, with troops and supplies to Fort Sumter. Citadel cadets assigned to a battery on Morris Island and troops at Fort Moultrie fired upon the ship on January 9, and it turned back without accomplishing its mission.

That same day Mississippi seceded; in short order Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana and Texas followed suit. On February 4, 1861, a convention of these seceded states met in Montgomery, Ala., and formed the Confederate States of America. On March 3, 1861, the day before Abraham Lincoln was sworn in as President of the United States, newly commissioned Confederate Brig. Gen. P. G. T. Beauregard assumed command of all troops, “in or near Charleston Harbor.”

As March turned to April, Fort Sumter began running low on rations and, following much deliberation, Lincoln decided to re-supply and hold the fort. On April 4, Secretary of War Simon Cameron sent a message to Anderson that a naval expedition would attempt the action, “and, in case the effort is resisted…to reinforce you.” Four days later, a messenger from Cameron arrived in Charleston to inform Pickens and Beauregard of the planned expedition. The information was telegraphed to Montgomery, and on April 10, Confederate Secretary of War Leroy P. Walker responded to Beauregard that if the intention was to “supply Fort Sumter by force you will at once demand its evacuation and if this is refused, proceed in such manner as you may determine to reduce it.”

The next day, April 11, members of Beauregard’s staff arrived at Fort Sumter demanding its evacuation. Again, Anderson refused, but in a conversation with the officers told them, “If you do not batter us to pieces we will be starved out in a few days.” This information was sent to Walker, who replied that if Anderson declared when he would leave the fort, hostile action could be avoided. The officers returned and Anderson responded that unless he received “controlling instructions from my Government or additional supplies,” and was not attacked, he would leave at noon on April 15. But with one of the relief ships already just outside the harbor’s entrance, the response was unacceptable. Anderson was informed that Fort Sumter would be fired upon beginning at 4:30 a.m. on April 12.

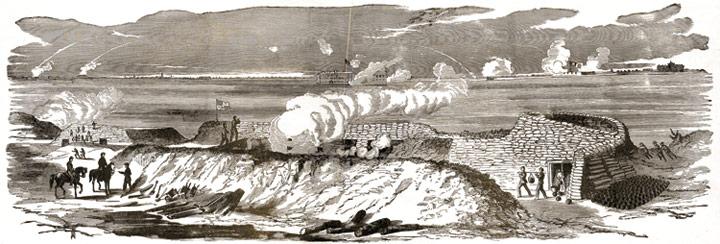

At the designated time, a 10-inch mortar shell, fired from Fort Johnson, exploded over Fort Sumter, beginning the Civil War. Soon, 43 Confederate guns and mortars opened fire from all directions. At about 7:00 a.m., Anderson responded in kind, with Capt. Abner Doubleday commanding the first gun that fired in defense of the Union.

Three times that day, Fort Sumter’s barracks caught fire, but each time the flames were extinguished. On April 13, hotshot from Southern batteries set the officers’ quarters ablaze, threatening the powder magazines. While some of Anderson’s men continued to fire their guns, others worked to remove powder to the casemates before securing the magazines’ doors against the flames.

Around 1:30 p.m., enemy fire destroyed the flag pole. Although the colors were quickly recovered and placed on the fort’s wall, during the interim, Col. Louis T. Wigfall arrived from Morris Island during the interim to begin unofficial negotiations with Anderson for a cease fire and surrender. Soon, other officers from Beauregard’s headquarters arrived and arranged a formal surrender and evacuation on April 14. Despite a 34-hour bombardment, Fort Sumter had suffered no significant damage to its exterior walls, but the enlisted men’s barracks and officers’ quarters had been gutted by fire. Fort Moultrie had likewise suffered some damage to its interior buildings, and minor damage had befallen some other Confederate defenses. Remarkably, no one had been killed on either side.

The surrender ceremony began around 2:00 p.m., on April 14, 1861. On round 47 of a planned 100-gun salute, a gun discharged prematurely, killing Pvt. Daniel Hough—earning him the misfortunate of being the first soldier to die in the war. The salute was reduced to 50 shots, and Hough was buried on the parade ground. Around 4:00 p.m., Maj. Robert Anderson led his command out of Fort Sumter while the band played “Yankee Doodle.”

Just before the Union troops left the fort, the Palmetto Guard and Company B, South Carolina Artillery Battalion took up position on the parade ground. Upon Anderson’s departure, General Beauregard, Governor Pickens and other dignitaries entered the fort to raise the South Carolina and Confederate national flags. Although Anderson’s men had boarded a ship to take them to the relief expedition waiting outside the harbor entrance, they were forced to wait for the next morning’s high tide to leave the fort’s dock and begin their journey north. They listened while all around them boat whistles sounded, cannons fired and men cheered. The Confederacy had achieved its objective: Fort Sumter was taken. The storm clouds of Civil War had broken open in Charleston Harbor, plunging the country into full-scale war.