Preservation of the Second Day's Battlefield

Hallowed Ground Magazine, 150th Anniversary Gettysburg

On the afternoon and evening of July 2, 1863, the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia and the Union Army of the Potomac engaged in an awful struggle at now-iconic locations like Cemetery Hill, Devil’s Den, Little Round Top, the Peach Orchard, Cemetery Ridge and the Wheatfield. By the time it was over, more than 20,000 were killed, wounded or captured, making it the costliest day of the Civil War’s greatest battle. People have used the more than 54,000 days since the battle to preserve, memorialize, exploit, interpret, promote and make sense of that single day’s battle.

On July 2, 1863, Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee advanced five of his infantry divisions against the Army of the Potomac, under Maj. Gen. George G. Meade, who had arranged his force in the shape of a fishhook. Southerners captured Devil’s Den, the Peach Orchard and portions of Culp’s Hill and, for a time, held on to Big Round Top, the Wheatfield, and East Cemetery Hill. But the Union line held firm, and Lee was unable to capitalize on his gains the next day.

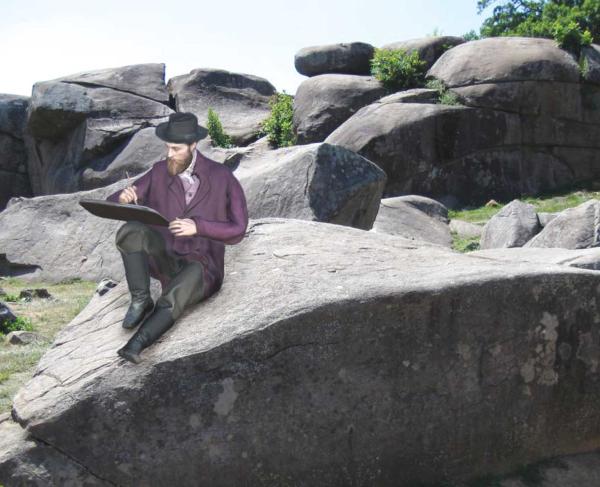

The blood-stained second day’s battle sites were particularly atrocious in the wake of the battle — to the soldiers, local citizens and visitors who toured the field and contemplated the impossible scenes firsthand. Reporters sent graphic accounts of the indescribable sites and scents to newspapers across the country. Photographer Alexander Gardner reached the field before all the dead had been buried and captured more images of the war’s human toll than on any other battlefield. In fact, more than 25 percent of all known photos showing Civil War dead on the field were recorded at just two second day places — Devil’s Den and the Rose Farm. Many of the areas where the armies struggled on July 2 were particularly rocky, which made digging graves a difficult chore.

Heroes on a New Battlefield

As local citizens recovered and cleaned up the worst of the damage and detritus in the battle’s wake, some recognized the national importance of the recent struggle and began to focus on preservation. It is no surprise that second day’s battle sites were the first to be preserved. Today, the Gettysburg battlefield consists of more than 8,000 protected acres, but it all started in the summer of 1863, with a 10-acre plot on East Cemetery Hill, where Union soldiers rallied on July 1, and which Confederates briefly succeeded in capturing in the next day’s twilight. Soon, portions of Little Round Top, with its extant stone breastworks, and Culp’s Hill, which saw action late in the day on July 2 and was the location of entrenchments and bullet-ridden trees, were preserved. Part of the crest of Cemetery Hill was secured as a final resting place for “they who fought” there. Local citizens swiftly formed the Gettysburg Battlefield Memorial Association (GBMA), and over the next three decades the group preserved the core of the battlefield we know today.

But the GBMA’s early efforts preserved disparate portions of the Gettysburg Battlefield, leaving most in private hands. The door was open for a wide variety of services in support of additional preservation, visitation, memorialization and commercialization. For the first few decades after the war, commercial intrusion was minimal. Some rocks on Little Round Top and Culp’s Hill sported advertisements for liver pills and German bitters. Commercial enterprises sprouted up here and there to serve the needs of tourists, including a 40-foot tower on East Cemetery Hill that visitors could climb, for a fee, to observe the landscape. Most battlefield activities and improvements during this time were implemented by local citizens and veterans with significant assistance from various states — whose legislatures were populated largely by veterans. Veterans who had become dissatisfied with the GBMA’s work took over the organization in the late 1870s and brought a renewed energy for preservation.

The fighting at Gettysburg produced its fair share of heroes, and the North was eager to erect monumental guideposts to honor its budding legends. While the tendency to honor individuals, most often generals, on the battlefield continues to this day, the focus of memorialization gradually shifted. The scope broadened, placing emphasis on units and, starting in 1879, an enormous swell of unit-based markers began to dot the field. Today, the majority of battlefield memorials are unit-based, and a disproportionate number of these were placed on the second day’s battlefield. This focus helps visitors to understand the flow of battle. Flank markers, monument inscriptions and, eventually, inscribed plaques for all the brigades, batteries, divisions and corps in both armies provide a clearer interpretive experience.

Playground or Battleground?

By the time the War Department established a three-man Gettysburg National Park Commission “to oversee the expenditure of a Congressional appropriation of $50,000 to survey, locate and preserve the lines of battle at Gettysburg” in 1893, commercial interests had gained a greater foothold. In 1884, the Gettysburg and Harrisburg Railroad constructed a spur from Gettysburg to Little Round Top, setting the stage for the commercialization of the second day’s battlefield. The pressure only increased with the construction of the controversial Gettysburg Electric Railway — a trolley connecting the town of Gettysburg with the south end of the battlefield and the railroad spur’s terminus on the east side of Little Round Top. Many veterans opposed the new line as boulders were blasted and tracks were laid across some of Gettysburg’s most hallowed ground. Despite resistance, so-called amusement parks sprouted up along the trolley’s path on the second day’s battlefield,

William Wible entertained people along the trolley line on the Rose Farm at his “Wible Woods” park with music, dancing and beverages. William Tipton welcomed guests to his Tipton Park, opposite Devil’s Den, where visitors could enjoy his restaurant and dance floors, or have their tintype pictures taken, all while drinking bottled, gin-based concoctions. By far the largest of the commercial establishments was Round Top Park on the eastern side of Little Round Top. This sprawling series of amusements included dining rooms, a dancing pavilion, a saloon, fresh spring water and a photographic studio amid a “perfume of a carpet of wild flowers and natural awning of leaves to check the sun’s rays… the fittings of this paradise.”

Tens of thousands of people visited these establishments each season — on a busy day, Tipton claimed to welcome as many as 3,000 guests — and the demand spawned more facilities. Round Top Park grew to such an extent that a small town known as Sedgwick sprung up around it. In time, a relic pavilion, merry-go-round, roller rink, casino and more eateries thrived in or around Round Top Park. Many visitors would come to Gettysburg and spend all their time in these amusement parks to the exclusion of the adjacent battlefield.

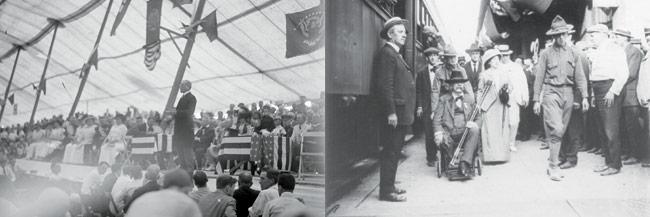

In 1895, the Gettysburg National Military Park was established and the GBMA transferred all of its land holdings to the U.S. government, under the umbrella of the War Department. Its three-man commission, led by Civil War veteran John Page Nicholson, made the government’s opposition to these commercial activities known.

The commission initiated condemnation proceedings against the trolley and Tipton Park, a process that would take decades and ultimately reach the U.S. Supreme Court. In the meantime, the commission established a guard corps, started licensing photographers and battlefield guides who operated in the Gettysburg National Military Park, erected five observation towers around the battlefield (the East Cemetery Hill Tower was removed in 1895) and cleaned up the new military park in general. Things improved:

Into the 20th Century

If the GBMA can be credited with preserving the core land of the Gettysburg Battlefield we see today, the Gettysburg National Park Commission should get credit for how we see it. The commissioners kept busy, meeting with veterans and marking positions. They hosted encampments in the Wheatfield and elsewhere, created the best maps for the time and bought key battlefield land—lots of it. By 1902 Tipton Park was condemned, and within about a decade the trolley tracks, railroad spur and the last vestiges of this commercial encroachment at Little Round Top were gone.

By the time the National Park Service (NPS) became the battlefield’s steward in 1932, land holdings had increased from 600 acres to more than 2,500 acres. The War Department had overseen the park for nearly four decades and proved an excellent steward through active participation in every aspect of preservation, restoration, interpretation, maintenance and protection.

The NPS, which has now overseen the Gettysburg National Military Park for 80 years, faced particular challenges at the outset. The NPS took over during the Depression, when both visitation and funding were down. World War II presented new challenges. In 1942, with metal at a premium, the park was asked to consider which of its metal assets might be contributed toward the substantial war needs. Some items were obvious, and the park quickly divested itself of postwar guns, fences, old signs, and obsolete vehicles. After tens of thousands of pounds of metal were sold to the war effort, another round of scrapping was contemplated that included the statuary and hundreds of bronze plaques — more of which occupy the second day’s battlefield than any other — but it was largely averted. In the end, the statues and bronze plaques that remain serve as reminders of not only the battle but of the generational contributions of service men and women.

The Battlefield We Know

The Civil War centennial, 1961–1965, ushered in a new level of interest in Civil War sites, as well as a different approach to the visitor experience. Tourists were now taken to visitor centers placed at the heart of where the action had occurred. At Gettysburg, the construction of the massive new NPS-constructed Cyclorama building in the 1960s and the private 393-foot National Tower in 1970s highlighted the new approach. Both of these facilities were situated near Cemetery Hill and placed a heavier interpretive focus upon third day sites.

Even as these projects, which might now be called “preservation mistakes” were propagated, the NPS was still securing more land on the second day’s field during the 1970s and 1980s. The Rose Farm, which historian William A. Frassanito discovered to be the site of the largest group of photographed dead soldiers, was preserved, as was more land west of Devil’s Den. The pace of preservation has quickened in the last three decades.

Interest ran high in the wake of the 125th anniversary of the Civil War, 1986–1990. The impact of the Ken Burns’ 1990 PBS documentary series, The Civil War, in combination with the 1993 release of the Turner movie Gettysburg created a legion of Gettysburg enthusiasts who, in following the emphasis of these productions, were particularly interested in second day sites. Yet, the enthusiasm of visitors seeking out fictional characters on Little Round Top and ghost hunters scouring Culp’s Hill and Devil’s Den was tempered by a waterfall of new scholarship, earnest heritage tourists and a preservation boom.

The Civil War Trust’s predecessor organization, the Association for the Preservation of Civil War Sites, was founded in 1987 amidst skyrocketing Civil War interest. The Trust, the Friends of the National Parks at Gettysburg, which later merged with the Gettysburg Foundation, and other local organizations, such as the Land Conservancy of Adams County, have partnered with the NPS to usher in an unparalleled era of preservation and advocacy at Gettysburg.

Land holdings of the NPS and preservation partners are now more than triple the 2,500 acres that the NPS began with 80 years ago. The Cyclorama and the National Tower are both gone. On two occasions, with the help of local groups, the Civil War Trust has blocked proposed casino operations at Gettysburg. And the second day’s battlefield looks much more like it did in 1863 than it has at any time in the last century — treelines are more accurate, deer herds are smaller, orchards have been replanted, historic houses look like they did in the 19th century.

What to do with this increasingly authentic and well-preserved battlefield? It’s up to you. New tools abound. Tour the field on a Segway, in a car or the old fashioned way — on a horse. Do as people have done for more than a century — hire a battlefield guide to accompany you in your vehicle — or pick up one of the Civil War Trusts smartphone-based Battle App™ guides. You can even tour Gettysburg from your home, using an increasing array of web-based digital products. No matter how you choose to see or engage Gettysburg, however, the various approaches are only possible because of the dedicated efforts of numerous organizations and individuals over the last 150 years who were dedicated to the preservation of this hallowed ground.

Related Battles

23,049

28,063