“No Man Can Take Those Colors and Live”

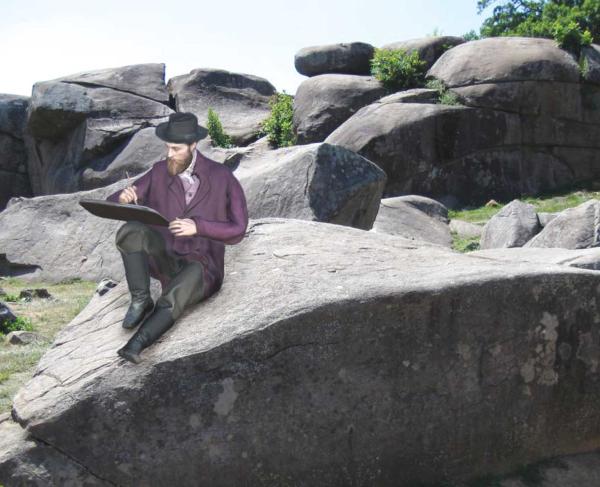

The Civil War Trust, in conjunction with the Conservation Fund, in 2011 saved the 95-acre Gettysburg "Country Club Tract." This section of the Gettysburg battlefield includes the location where the 24th Michigan ended their morning assault on July 1, 1863 and where the 26th North Carolina began their bloody attack upon the Iron Brigade.

“Forward men, forward, for God’s sake, and drive those fellows out of those woods.”

By 10:00 on the morning of July 1, 1863, the situation near McPherson’s Ridge, outside the town of Gettysburg, was becoming increasingly desperate for the Army of the Potomac. Tennessee and Alabama soldiers from James Archer’s Brigade had already crossed over the open field in front of Herr Ridge, splashed across the tangled stream bottom at Willoughby’s Run, and were now pressing up through the Herbst (or McPherson’s) Woods. The Union cavalry screen that had been gallantly holding the ground west of Gettysburg was simply no match for the huge Confederate force converging upon the strategic town.

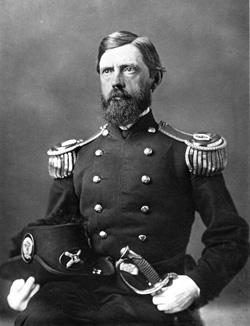

Fortunately for the Army of the Potomac, the veteran Iron Brigade, among the toughest units in the army, was just arriving on the western outskirts of the town of Gettysburg, near the prominent Lutheran Seminary. The first regiment to arrive, the 2nd Wisconsin, was hustled down to the edge of Herbst Woods by Left Wing commander Maj. General John Reynolds himself. Shortly after entering the woods, Reynolds, who was still conspicuously mounted on his horse, was struck by a bullet, reeled from his saddle, and fell to the ground, dead. The popular Reynolds was the highest ranking general killed at Gettysburg and his death had a profound impact upon the rapidly developing Union defenses on July 1st.

The 24th Michigan followed closely on the heels of the 2nd Wisconsin and advanced so fast that the men lacked time to load their rifles before entering the smoke filled woods to the left of the 2nd Wisconsin. Joined by the 19th Indiana and 7th Wisconsin, the Iron Brigade now had roughly 1,450 men positioned to take on the 1,200 soldiers in Archer’s Brigade.

Reaching the southern edge of Herbst Woods, the Michigan men were quickly greeted by Confederate bullets. Color Sergeant Abel Peck of the 24th was killed straight off and the regiment’s colors were quickly grabbed by Corporal Charles Bellore before it hit the ground. Despite the growing enemy fire, the 24th pressed forward.

“He who fights and runs away may live to fight another day”

Legend has it that the Confederate soldiers of Archer’s Brigade, who thought at first that they were facing inexperienced local forces, saw the soft-brimmed Hardee hats worn by the Iron Brigade and exclaimed, “there are those damned black-hatted fellows again. ‘Taint no militia. It’s the Army of the Potomac.” As more of the tough westerners from Wisconsin, Indiana, and Michigan filed into the woods, Archer’s men began to slowly fall back towards Willoughby’s Run. Little did they know, time was already rapidly running out for Archer’s Brigade.

Pressing further into Archer's right flank, the 24th Michigan and the 19th Indiana struck and overlapped the 13th Alabama, forcing them to rapidly retire towards Herr’s Ridge. Col. Henry Morrow of the 24th then directed the Michigan troops across Willoughby’s Run and into the rear of the Tennessee regiments who were busy holding off the rest of the Iron Brigade. Pressed in front, flank, and rear, many of Archer’s men barely escaped the Union vise. Upwards of 200 Confederates who failed to run early, including General Archer himself, quickly surrendered to the Iron Brigade.

Despite taking heavy casualties during the morning counterattack, the Iron Brigade had performed brilliantly once again. With Archer’s Brigade now driven back or captured, the Union troops pressed forward across Willoughby’s Run and into the open fields beyond. A quiet lull took hold around noon on the 1st.

Heth’s Second Assault on McPherson Ridge

Maj. Gen. Henry Heth knew that he had failed to do his best in deploying his division during the morning’s fight. Feeding his regiments into the fight west of Gettysburg, he had expected that his veteran infantry would have little trouble driving off whatever mixture of cavalrymen and militia lay to his front. But with the arrival of strong Union infantry units, all of Heth’s forces south of the Chambersburg Pike had been driven back. Looking over the land in front of him, Heth was determined that his afternoon attack would deliver the victory that he knew was expected of him.

Sensing that the day’s fighting was far from over, Brig. Gen. Solomon Meredith, commander of the Iron Brigade, brought his forces back across Willoughby’s Run and placed his regiments into a compact line inside Herbst Woods. The 24th Michigan was moved to the center of this line, with the 19th Indiana on its left and the 7th Michigan on its right. The 2nd Wisconsin, having suffered the heaviest casualties during the morning fight, was initially placed in a second line to the rear.

With the afternoon heat reaching its peak, the North Carolinians and Virginians of Pettigrew's and Brockenbrough’s Brigades stepped off from their positions on Herr’s Ridge to resume the attack upon the Union forces defending McPherson’s Ridge, south of the Chambersburg Pike.

Enter the 26th North Carolina

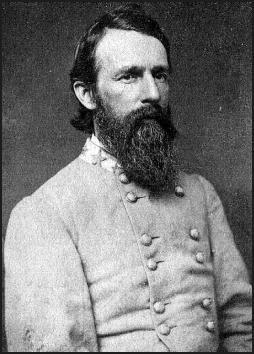

With 843 soldiers, the 26th North Carolina was the largest regiment not only in Pettigrew’s brigade of roughly 2,500, but the largest in either army at Gettysburg. Commanded by the “boy general”, 21-year old Colonel Henry King Burgwyn, the officers of the 26th were anxious to enter the fight before the day was done. Finally, at 2:30pm, the 26th and the rest of Pettigrew’s Brigade was ordered forward.

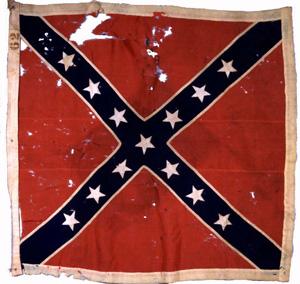

With Col. Burgwyn taking his place at the center of the regiment, J.B. Mansfield, the regimental color bearer stepped out in front of the line with the regiment’s square battle flag. Eight other members of the 26th's color guard joined Mansfield at the front. “Forward! March!” came the order.

The 26th North Carolina maintained perfectly dressed lines as they descended into the wheatfield in front of Willougby’s Run. Fortunately for the Tarheels, the Yankees opposing them fired high. The 26th paused to return fire and then made a dash for the tangled banks of Willoughby’s Run.

While most of the regiment made it safely to the banks of Willoughby’s Run, the 26th’s color guard, always a tempting target, suffered much heavier losses. Four members of the 26th’s color guard were killed or wounded before they even reached the stream. Private John Stamper grabbed the regiment’s colors as they entered into the brush near the stream but fell before he made it across. Private George Washington Kelly next took up the battle flag. Leaping across the water, Kelly fell to the ground, hit by shrapnel in the leg. Kelly’s friend, L.A. Thomas, picked the flag up and began to move up the hillside. Thomas, like so many before him, was hit shortly afterwards and handed the flag to John Vinson. Vinson, in turn, was promptly wounded and the flag was passed to John Marley who was quickly dispatched by a hissing bullet. A tenth, unnamed man, took his turn holding the colors. In just ten minutes the 26th North Carolina had used ten different color bearers.

The men of the 26th North Carolina soon “came on with rapid strides, yelling like demons.” Up the steep bank they came. Waiting in the thick woods were the trained rifles of the 24th Michigan.

With Burgwyn’s men crowding into the stream bottom, Col. Henry Morrow of the 24th ordered his men to hold their fire until the terrain allowed for a clear shot. The men of the 26th swarmed up the far bank and on towards the forested positions of the 24th Michigan. Now seeing the distinctive Hardee hats on the heads of the Michigan men, some of Burgwyn’s men exclaimed, “here are those damned black hat fellows again.” With barely 40 yards separating the two lines, the 24th Michigan unleashed a devastating volley upon the Tarheels.

The superior numbers of the North Carolinians, however, began to overwhelm the 24th Michigan. Quickly stepping back to their second prepared line, the 24th looked to stem the onslaught as best they could. Corporal Charles Bellore, who had carried the 24th’s colors since Sergeant Peck’s death during the morning assault, was killed near the second line.

“No Man Can Take Those Colors and Live”

The battle between the 26th North Carolina and the 24th Michigan rapidly reached its climax. Standing toe to toe in the deep woods, the two proud regiments poured deadly fire into each other. Col. Burgwyn, yelling words of encouragement and praise, took up the 26th’s colors and stepped forward. With the 26th’s men reforming on their colonel and colors, Private Frank Honeycutt moved forward to take the flag from his colonel. As Burgwyn turned to hand the flag to Honeycutt the boy colonel was struck by a bullet to the chest. As Burgwyn fell to the forested floor he was momentarily held aloft within the folds of the battle flag that he so proudly held. Honeycutt would share his colonel's fate with a bullet to the head.

Lieutenant Colonel J.R. Lane, after checking on the mortally wounded Burgwyn, quickly assumed command of the regiment. “Close your men quickly to the left. I am going to give them the bayonet” he yelled. As the 26th North Carolina’s men prepared for yet another charge, their flag lay on the ground in front. Lieutenant Blair of the 26th, seeing the prostrate flag and knowing its recent history, exclaimed, “no man can take those colors and live.” Lane concurred, but picked up the flag nonetheless and yelled, “twenty-sixth, follow me.”

The tenacity of the 26th’s assault forced the 24th Michigan back to a third line in the woods. As the 24th took up station on their new line, Private August Earnest, holding the regiment’s colors, was killed. Colonel Morrow himself took the colors from 1st Sergeant Everard Welton. The Michiganers continued to fall all around Morrow.

Unbeknownst to Col. Morrow and the 24th, the 19th Indiana, the regiment on their left had begun to give way under the heavy assault. With their left flank now threatened, the 24th was forced to begin its retreat back towards the safety of Seminary Ridge.

Following quickly behind the retreating 24th was the remains of the 26th North Carolina. Lieutenant Colonel J.R. Lane, still carrying the regiment’s flag, continued to urge his men forward. But like all the preceding color bearers from the 26th this day, Lane too would be struck down. Lane would suffer a terrible bullet wound to the back of the neck. For the fourteenth and final time on July 1st, the colors of the 26th went down.

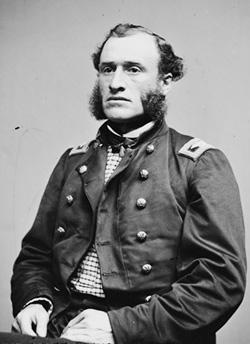

Lane’s counterpart, Colonel Henry A. Morrow of the 24th also become a casualty during the fight. Carrying his regiment’s flag up the slopes of Seminary Ridge, Col. Morrow received a non-lethal wound to the head. The injured Morrow struggled back to the town of Gettysburg before being captured by Confederates who later occupied the town.

"Ranks went down like grass before the scythe"

The shattered remains of the Iron Brigade filed quickly behind a barricade of rails erected on Seminary Ridge and awaited the next assault from the Confederates. Captain Albert Edwards, now in command of the 24th Michigan, began to quickly look for the regiment's missing flag. After a few desperate moments, Edwards would find the tattered flag held in the arms of a dying soldier lying inside the barricade.

Despite suffering heavy losses of their own, the North Carolinians reformed and charged the Union positions on Seminary Ridge. As the Tarheels began their climb up the hill, the Federal soldiers and artillery held their fire. Waiting for the optimal chance to strike their enemy, the Union line unleashed a devastating fire that drove back the Confederate attackers. The hard-pressed Union soldiers would hold off one more attack, but it was becoming increasingly clear that this position too would need to be abandoned.

With both flanks heavily pressed, the survivors of the 24th Michigan would join the rest of their Iron Brigade brothers in a fighting retreat back through town and onto the relative safety of Cemetery Hill.

The fight between the 24th Michigan and the 26th North Carolina proved to be the bloodiest regimental engagement of the bloodiest Civil War battle. The 24th Michigan and the 26th North Carolina each suffered the greatest number of regimental casualties in their respective armies at Gettysburg. The 26th North Carolina entered the battle with 843 soldiers and incurred 687 casualties, including its colonel and lieutenant colonel. The 24th Michigan would lose 363 of their 496 soldiers at Gettysburg - a staggering 73% casualty rate. These two units suffered more casualties than any other regiments in their respective armies

Despite suffering enormous casualties on July 1st, both the 24th Michigan and 26th North Carolina would see even more combat later in the three day battle. The 24th Michigan was moved to Culp's Hill - the Union's vulnerable right flank - to help shore up that critical position. The 26th North Carolina, as part of Pettigrew's Brigade, participated in the fateful Pickett-Pettigrew-Trimble charge against Cemetery Ridge on July 3, 1863.

Related Battles

23,049

28,063