Mount Independence Throughout the American Revolution

In the early years of the American Revolution, American military strategists saw Canada both as a potential staging ground for a British invasion of the United States and as an alluring prize that could be added to the new nation. In the winter of 1775-1776, the Americans attempted to prevent a British incursion via Lake Champlain, Lake George and the Hudson River by launching attacks on the Canadian cities of Montreal and Quebec. It was an unmitigated disaster.

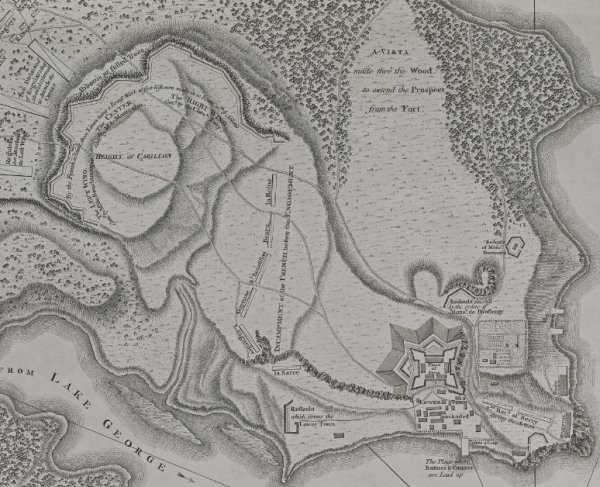

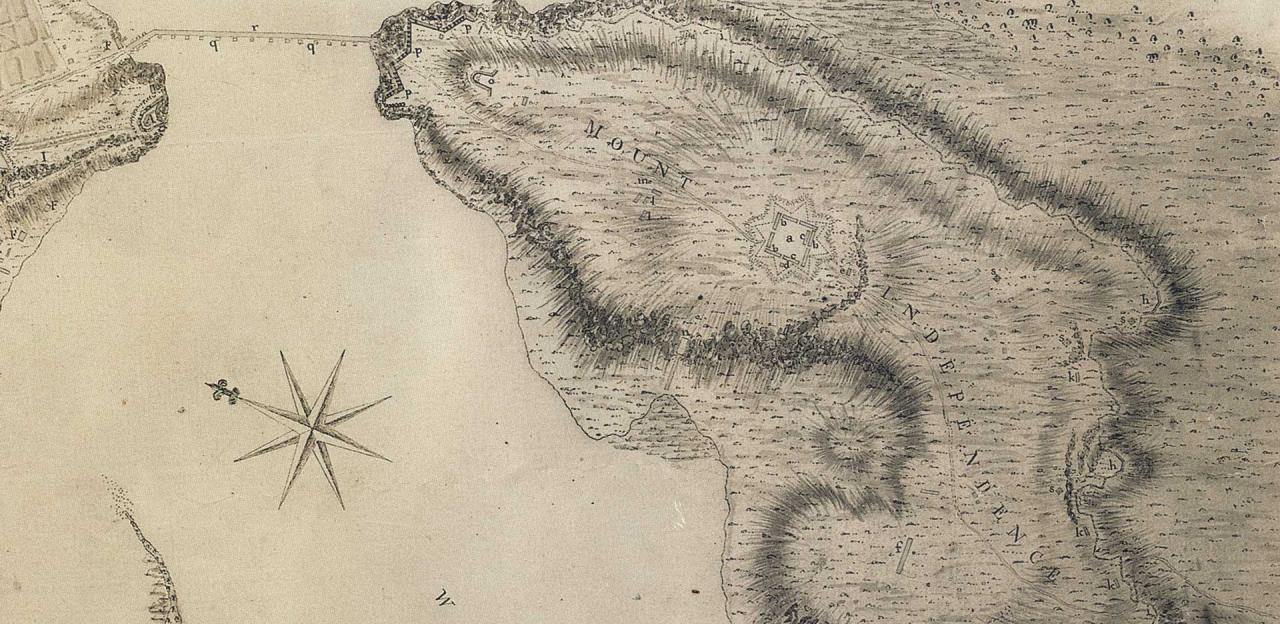

After suffering major losses, the Americans retreated south and gathered to recuperate at Fort Ticonderoga in New York, on the west bank of Lake Champlain. Anticipating that the British would follow them when the weather improved, the Americans built another fortification across from Fort Ticonderoga. This new addition meant that, should the British sail south down the lake, they would be forced to sail through an American gauntlet. In a letter to George Washington, Philip Schuyler, Commander of the Continental Army’s Northern Department, wrote the new fort’s position was, “so remarkably strong as to require little labor to make it tenable against a vast superiority of force, and fully to answer the purpose of preventing the enemy from penetrating into the country south of it.”

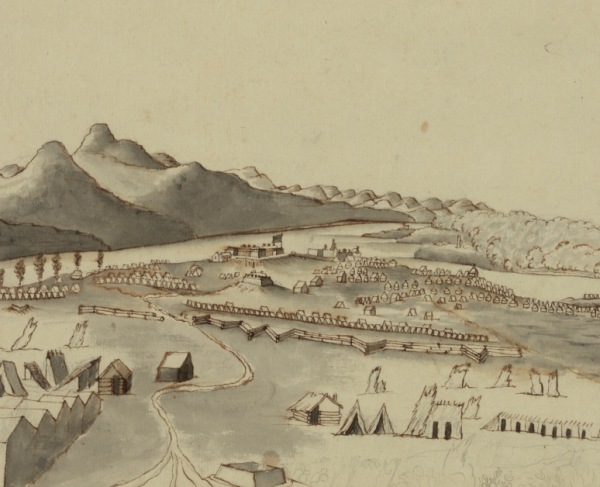

Though the fort was viewed as an impenetrable force upon completion, more than 20 of Schuyler’s subordinates objected to the initial construction. Regardless of their concerns, construction began in earnest on July 11, 1776 – trees were felled, huts built, and fortifications erected. Work continued sporadically at the fort as a series of commanders rotated in and out. Following a reading of the Declaration of Independence to the troops assembled at the fort, it was baptized as Mount Independence on July 28, 1776.

In the fall of 1777, in an effort to cut off New England from the remaining states, British General John Burgoyne launched the first part of a planned a three-pronged attack on Albany, New York. Burgoyne’s army mounted artillery on high ground opposite Fort Ticonderoga, and took the fort without firing a single shot. Schuyler ordered a retreat, which caused American morale to plummet. George Washington’s morale, too, was greatly affected when he heard the news. With the British occupation of Fort Ticonderoga, the position of Mount Independence became a liability. Schuyler ordered Mount Independence evacuated as well.

As the American army retreated it fought off elements of British pursuit units. During one such encounter at Hubbardton, an intense fire fight broke out between American and British forces. Although the British took the field, the fight bought the Americans a bit of respite as they continued their southward trajectory. British troops and German Hessians occupied the abandoned American positions at Ticonderoga and Independence.

On September 18, American forces tried to retake Fort Ticonderoga and Mount Independence, but failed. During the fight for Mount Independence the Americans demanded that the British garrison surrender. After the battle, one British officer wryly wrote, “It is an undeniable truth that the Mount was never attacked by the Rebels otherwise than by paper.”

Despite their initial failures, the Americans went on to defeat Burgoyne at Saratoga in October 1777, forcing the British to retreat back to Canada and reoccupying Fort Ticonderoga and Fort Independence.

Related Battles

18

5