Mansfield

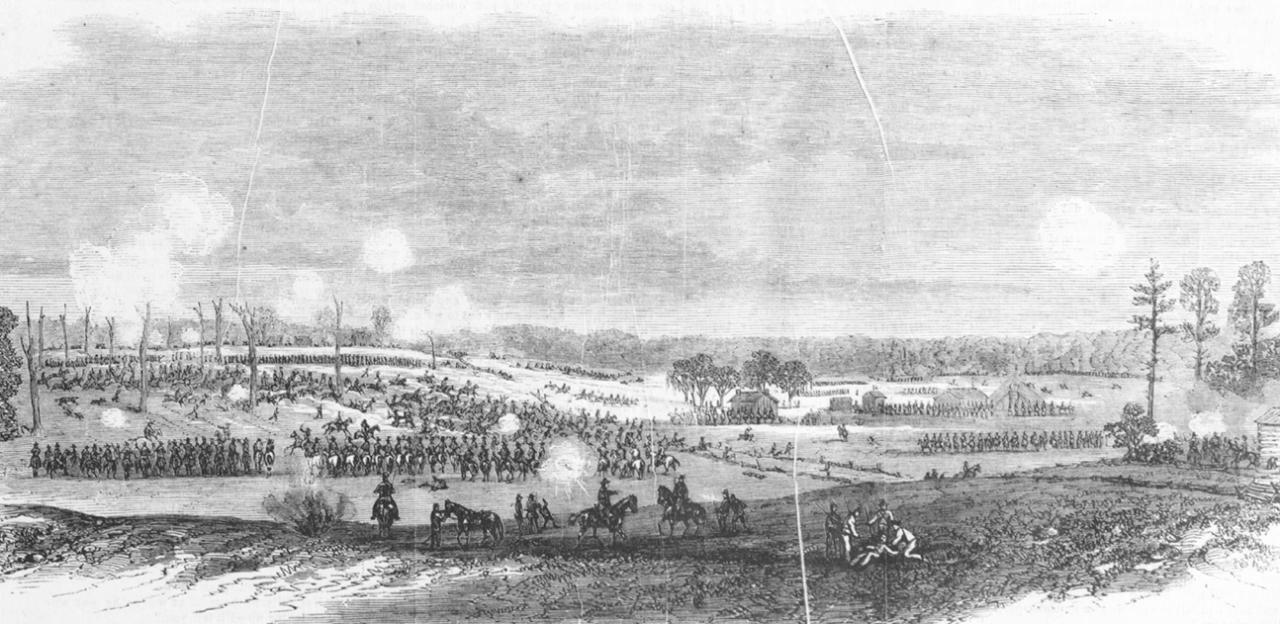

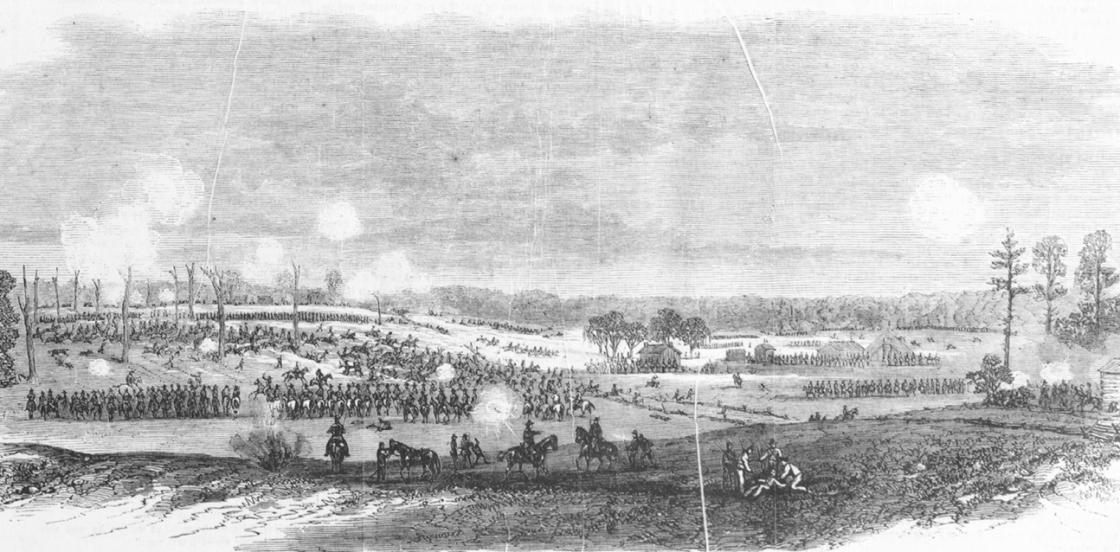

Mansfield — also known as Sabine Crossroads — lies about 40 miles south of Shreveport, Louisiana. There, on April 8, 1864, roughly 8,000 Louisianians and Texans led by Major General Richard Taylor stopped vastly stronger invasion forces commanded by Union Major General Nathaniel P. Banks and sent them scurrying back toward their starting point of New Orleans. Had Banks been victorious at Mansfield, his next objective would have been Shreveport — followed by a drive through East Texas. But Taylor and his men smashed the Yankees so severely at Mansfield that the Union's Red River Expedition became an expensive and highly embarrassing fiasco.

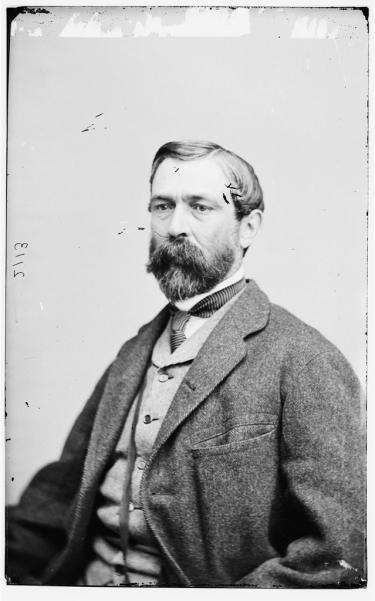

From start to finish, this Confederate achievement was the work of "Dick" Taylor. He was the son of Zachary Taylor, who was a general in the Mexican War and later President of the United States, and the brother of Jefferson Davis' first wife. Taylor studied history at places as varied as Yale, Harvard, and Edinburgh. When he commanded Louisiana brigades under General Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson in the 1862 Shenandoah Valley campaign in Virginia, however, it became apparent that Taylor was a "natural" soldier. After leading Jackson's sweep through Front Royal, Taylor drove Banks out of Winchester and whipped him again at Cross Keys. "Delightful excitement!" said Jackson as he greeted Taylor at Port Republic, then sent him up to capture Union artillery that had been bedeviling the Stonewall Brigade from high ground. Illness caused Taylor's reassignment to Louisiana before the Seven Days Battles, but — as Mansfield would demonstrate — it did not make him forget the lessons fighting with Jackson had taught him.

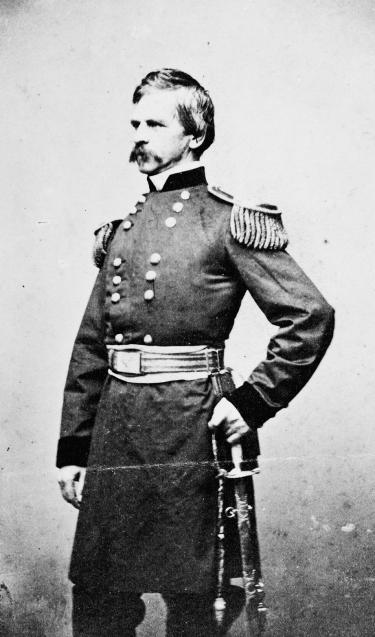

Taylor's opponent, Nathaniel Banks, rose from a job as a bobbin boy in a Massachusetts textile mill to governor of the Bay State and speaker of the U. S. House of Representatives. Abraham Lincoln appointed him a major general of volunteers despite his utter lack of military experience and kept him despite his appalling combat record.

Operators of Massachusetts mills, starved for cotton, advocated conquering Texas using men recruited with the expectation of receiving confiscated cotton-growing land as compensation. Banks was given the assignment. It was decided to send Rear Admiral David Dixon Porter's flotilla of gunboats and transports up the Red River to support Bank's troops in their advance to Shreveport. General Banks designated Alexandria — about 50 miles up the Red River from its junction with the Mississippi and 125 miles downstream from Shreveport — as the assembly point for his expedition. Porter's vessels arrived on March 17, but rains delayed Banks' units; while waiting, the sailors stripped the vicinity of cotton bales, which they claimed as prizes of Walt. By late March, however, Banks had gathered roughly 30,000 troops of all arms at Alexandria and Porter had succeeded in getting his gunboats and transports over a mile of exposed rock that — when the river was at its usual water level — was normally a series of rapids. "I can take my ships wherever the sand is damp," he had boasted.

With Porter steaming upriver and Banks marching his units up the west bank, Taylor set Mansfield as the concentration point for the forces under his command. Soon came the division led by Brigadier General Jean Jacques Alfred Alexander Mouton, son of a highly respected former governor of Louisiana, a West Point graduate who had been wounded at Shiloh. So did Brigadier General Camille Armand Jules Marie Prince de Polignac; he, too, had fought at Shiloh. Texans in his outfit who could not pronounce his name nicknamed him Polecat. From below Alexandria came Major General John G. Walker's division of Texas infantry. Major General Thomas Green was among the warriors Sam Houston had led to victory over Santa Anna at San Jacinto in 1836; he was a hero in the Mexican War, and in 1863 he had cleared Galveston Island of Yankees. Green and his cavalrymen arrived near Mansfield in early April, but about half of his troopers lacked weapons. Brigadier General James E. Harrison's Texan mounted infantry performed scouting duties; Brigadier General St. John Richardson Liddell's small cavalry units patrolled the Red River's east bank.

At Grand Ecore, near Natchitoches and roughly 75 miles south of Shreveport, General Banks decided to send Brigadier General Albert Lee with more than 3,300 cavalrymen and a train of at least 300 wagons up to Mansfield. From Mansfield, three roads led to Shreveport. Banks had promised General-in-Chief Ulysses S. Grant to be in Shreveport by April 10. From Grand Ecore Admiral Porter's flotilla would steam upriver to Shreveport's vicinity. Major General William B. Franklin, whose 20,000 infantrymen were waiting to follow Lee's cavalrymen up the Mansfield road, urged the expedition's commander to send scouts out to evaluate other routes to Shreveport. Nothing was known about the terrain that Lee would encounter or whether water would be available for his troops. Moreover, soon after leaving Natchitoches Banks' inland force would be beyond the range of covering fire from Porter's gunboats. But Banks did not believe there would be a battle on the way to Shreveport. No reconnaissance was made.

General Taylor had been unable to obtain Trans-Mississippi Department commander Lieutenant General Edmund Kirby Smith's permission to fight a general engagement. Indeed, Smith had declared Friday, April 8, 1864 to be a day of prayer and thanksgiving on which Confederate combat operations were to be suspended. But on Thursday Taylor had decided to stop withdrawing. Remembering Jackson, he choose a place where his small numbers — about 9,000 men — would be more than a match for Banks' advancing unit: Albert Lee's 3,300 cavalry. He found an ideal killing ground north of Sabine Crossroads, at a clearing surrounded by dense forests about three miles south of Mansfield on the road to Pleasant Hill. To make certain he would have enough time to prepare the trap, Taylor sent Tom Green with a cavalry force toward Pleasant Hill to retard Albert Lee's advance. After some skirmishing at Wilson's Farm, Green withdrew and Lee sent requests for reinforcements back to Franklin and Banks. Lee did nothing, however, about the 320 to 350 supply wagons clogging the road right behind the point of the advance of his two-to-three-mile column as it moved slowly through the tunnel formed by the forest on either side.

Not having heard from the department commander, on the morning of April 8 Taylor began placing his brigades in a rough crescent or "L" shape along the west, north, and east edges of the woods. On Honeycutt Hill in the clearing's center he put a regiment of cavalry as bait. Soon Albert Lee was replacing the departed Confederate bait with one Yankee outfit after another. For hours Taylor and his men watched. First he sat on a stump, smoking a cigar, then he rode along the crescent making a few adjustments; finally he sat on his horse, smoking, his leg over the saddle, mindful that daylight was slipping away.

Albert Lee's reports to Banks inspired the Union commander to send an order to Lee to attack and seize Mansfield forthwith. Lee rode back to protest. "I told him," Lee testified afterward, "we could not advance ten minutes without a general engagement in which we would be most gloriously flogged." Soon after Lee returned to the hill, General Mouton — whose division Taylor had promised the honor of drawing the first Yankee blood — attacked. So did Polignac's brigade and Green's Texans. Walker's cavalry came at Lee's other flank yelling like banshees. Mouton was killed; Polignac replaced him and drove the invaders back down the road by which they had entered.

Taylor's men captured three Union artillery pieces and turned their fire on their former owners, now fugitives streaming past General Banks, oblivious to his cries of "Form a line here! I know you won't desert me!" But desert him they did, throwing away their weapons and ammunition and everything they had with them as they fled through Confederate crossfire into the thickets where panicked teamsters had tried and failed to turn wagons around, blocking the road. General Franklin's horse was shot under him and then he was wounded. "Go back! To Pleasant Hill!" beaten soldiers in a state of fear and frenzy shouted at arriving infantrymen, lest they all be slaughtered.

As Banks' army was falling apart, a messenger from Department Headquarters in Shreveport reached General Taylor. Told he was to avoid a general engagement, he replied: "Too late, sir. The battle is won!"

Banks' troops did not stop running until they reached Pleasant Hill. Taylor attacked again late the next afternoon planning to complete the destruction of the Union force. Thanks to a valiant move by Federal Brigadier General A.J. Smith's veterans, Taylor's attack was turned into a Confederate rout — but Banks did not follow up on his success. The Federals continued the retreat that would terminate where the fiasco had originated, in New Orleans. The people of the Louisiana and Texas would not be molested again for the rest of the war.

Curt Anders is the author of "Disaster in Damp Sand: The Red River Campaign" and "Injustice on Trial: Second Bull Run, Major General Fitz John Porter's Court-Martial, and the Investigation by the Schofield Board That Restored His Good Name."

Related Battles

2,117

1,000