Lincoln's Voice

Hallowed Ground Magazine, Winter 2010

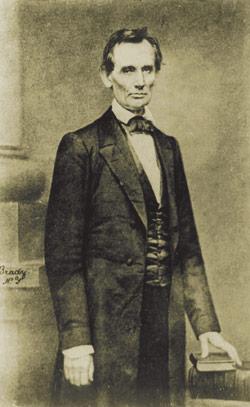

Perhaps the single most critical voice of the secession crisis belonged to President-elect Abraham Lincoln, whose victory at the polls in November 1860 drew the long-simmering issues of regional difference, resentment and conflict to a head. The election of a candidate from the fledgling Republican Party, whose platform was rooted in halting the spread of slavery, threw the Deep South into a panic. Southern newspapers fanned the flames of fear, insisting that the “rule of Lincoln” would mean the destruction of Southern society, up to and including the murder of slaveholders.

From his many speeches delivered to audiences across the nation, as well as his private correspondence, it is clear that Lincoln was firmly committed to the perpetuity of the Union, although he did not approve of the policies of appeasement and compromise pursued by his predecessors in the Oval Office. While, certainly, he abhorred the idea of war or the acceptance of slavery, he placed the principal of union above both and made it clear that he was willing to fight for it, if necessary. In an 1856 speech at Galena, Ill., Lincoln declared: “The Union ...won’t be dissolved. We don’t want to dissolve it, and if you attempt it, we won’t let you. With the purse and sword, the army and the navy and the treasury in our hands and at our command you couldn’t do it.”

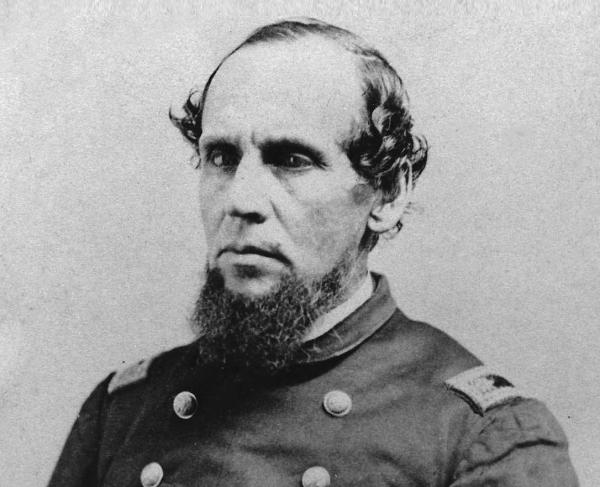

Waiting to take office, Lincoln continued to demonstrate his willingness, though not eagerness, to take extreme measures in the name of union. He directed Gen.Winfield Scott, the army’s general-in-chief, “to be as well prepared as he can to either hold or retake the forts, as the case may require, at, and after the inauguration.” Potential consequences, however, were great. When warned, in late February 1861, that a hostile action would almost certainly prompt Virginia to join the ranks of the burgeoning Confederacy, Lincoln responded that for the continued loyalty of Virginia, he would withdraw troops from Fort Sumter. “A state for a fort is no bad business,” he famously quipped.

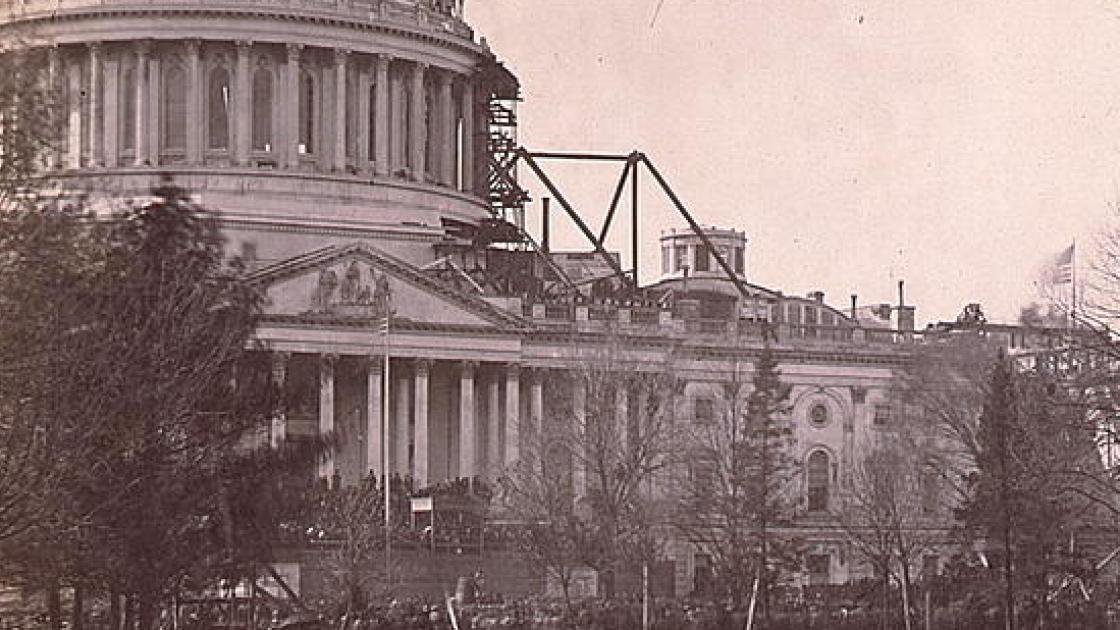

The ultimate expression of Lincoln’s philosophy on these points came in the form of his inaugural address. While he assured the waiting world that “the power confided in me will be used to hold, occupy and possess the property and places belonging to the government,” he pledged that he would not order the opening volley of any conflict.

“In your hands, my dissatisfied fellow-countrymen, and not in mine, is the momentous issue of civil war. The government will not assail you. You can have no conflict without being yourselves the aggressors. You have no oath registered in heaven to destroy the government; while I have the most solemn one to ’preserve, protect, and defend’ it.”

The message was clearly received by at least one member of the Confederate cabinet. Just one month later, contemplating opening fire on Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor, Secretary of State Robert Toombs cast the lone dissenting vote, saying, “You will wantonly strike a hornet’s nest.... Legions now quiet will swarm out and sting us to death. It is unnecessary. It puts us in the wrong. It is fatal.”