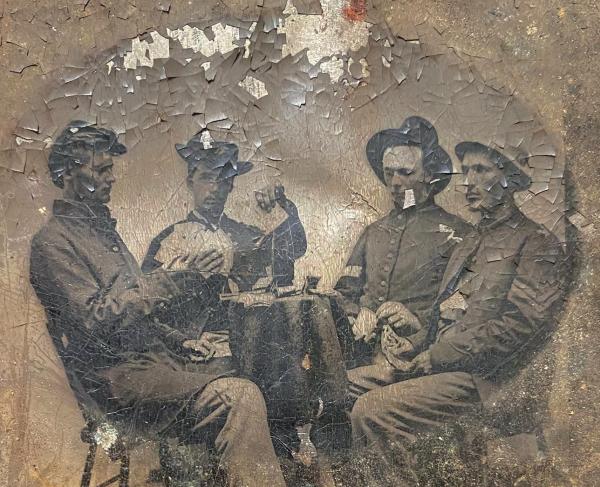

Life of the Civil War Soldier in Battle

Just like the soldiers of every conflict before and since, the men who fought in the American Civil War enlisted for a multitude of reasons. To claim any universality for these soldiers and the divided nation they represented would be a mistake, with perhaps one exception — their expectations were vastly different from the actual experience of military engagement.

Due to the wide background of experiences and attitudes and the transformative nature of combat, soldier motivation ultimately should be viewed as a progression. Historians have generally broken this down into three fundamentals: what spurs men to enlist, what steadies them on the firing line or pushes them forward in the assault and what keeps them in the service through the end. Analyzing the war through the lens of one individual can illustrate the variety of motivational factors and different fates a Civil War soldier realized.

Charles Carroll Morey, from a large family in Royalton, Vt., enlisted as a corporal in the 2nd Vermont Infantry in 1861, just before his 21st birthday. No driving personal ideology rationalized his service. Instead, like many around him, he believed the pending war to hold great importance, even if he could not particularly define the patriotic instinct or adventurous excitement that spurred him into the ranks. Throughout his service, Morey captured his experiences through meticulous diary entries and honest letters home.

He did not seem to think much of his first experience “seeing the elephant” at Bull Run. “[S]ince the fight there seems to be considerable discontent,” he wrote his sister, “but it is all caused I think by the hard march which we have not got over and the poor fare we have had….” Many soldiers, after experiencing battle, believed that civilians back home could have no way of understanding the events and emotions of combat and focused their writing to more relatable occurrences. “I cannot write it therefore will not try,” Morey admitted to his mother after another fight.

Unexpected adversity tested Morey’s resolve, as danger lurked even where the enemy did not. After the Seven Days’ Battles near Richmond in 1862, one of his friends, Sgt. George E. Allen, drowned in a creek near the regiment’s campsite. Morey described this loss, just on the heels of an especially trying engagement, as “the most severe blow this company ever sustained.” Such sudden, inexplicable tragedies were tough to handle, even in a war in which twice as many soldiers died away from the battlefield as on it. “[H]e was always at his best in time of danger and did not fear to sell his life dearly if necessary in the cause in which he was engaged,” Morey eulogized.

Nineteenth-century Americans accepted a certain rubric for the proper way to face death. A dying individual should be at home with family around to see them off into the next world. The battlefield clearly denied realization of this standard, but a surrogate could be attained through mortally wounded soldiers offering last words home to comfort and reassure their families. During the battle of Second Fredericksburg on May 3, 1863, a minié ball struck Pvt. Frederick W. Chamberlin in the neck as the 2nd Vermont aided the Union assault on the Confederate lines. Chamberlin’s friends surrounded him and urged him to communicate a message back to his family, as his wound seemed fatal. “Tell them that I was a good soldier,” Chamberlin asserted, before succumbing, a statement that Morey could vouch for. Morey wrote, “he was one of the best soldiers in the company and he came to his end in the line of duty defending that ‘old flag which so proudly waves’ ore the land of the free and the home of the brave.”

As the war progressed, the frequency of combat escalated with no reduction in intensity. Nearly a year to the day later, the Vermont Brigade faced the task of defending a crucial intersection on the Wilderness Battlefield. During the fight, one of Morey’s comrades knew immediately of the mortality of his wound, crying, “Oh! I am killed!” before falling. Now serving as orderly in his company, Morey felt responsibility for searching the deceased’s pockets for items worthwhile to send home.

At Spotsylvania’s Bloody Angle, Morey offered one of his most personal recollections of combat. “[S]oon after we arrived on the ground we were firing and just after I had discharged my piece at a Johnnies head I turned to reload and while in the act of charging cartridge I saw a Reb who had got sight of me across his musket, and I can assure you my legs grew very short in a very short space of time or else there was a joint in them, that is to say I dropped down out of his sight just in time to hear his bullet whistle over my head. Then knowing the danger had passed I straightened up and finished loading.” Having survived the horrors of the start to the Overland Campaign, Morey reflected on his ordeal. “It is with gratitude to God that I am permitted to write you a few lines once more. I don’t know what to say first but will say praise God for his goodness in sparing my life while so many of our brave comrads have fallen victims to the enemy’s shots….”

With no end to hostilities in sight, and the armies engulfed in constant daily fighting, Morey, now a lieutenant, strove to keep his presence felt at home, consistently inquiring about minute domestic details and offering his advice in any matter. This compartmentalization helped maintain a civilian identity and served to rationalize the violence in which he participated. Nevertheless, the psychological transformation required of the citizen soldiers who composed both armies concerned Morey. “[S]ociety will not own the rude soldier when he comes back, but turn a cold shoulder to him, because he has become hardened by scenes of bloodshed and carnage,” he worriedly expressed in a letter. “I tell you, dear sister, there are feelings, tender feelings, down deep in the soldier’s breast, which when moved will prove that all that is good is not quite dead.”

Thoughts of home continued to dominate his thoughts, yet he understood the only proper way he could return. After Cold Harbor, he told his mother that he would be very happy to return home “if there was no war to call me into the field but as it is the war must be settled then I will come home and try to be content with a quiet citizen’s life.” Having transferred to the Shenandoah Valley, Morey suffered a wound in August that forced him to the hospital. “I think it is wrong for one who is able to do duty to stay away,” he wrote, “yet it is not my fault that I am here.” Duty often compelled soldiers to take early leave from the hospital to reunite with their comrades in the field. Upon his return to his unit, which saw his promotion to captain, Morey felt “as though I had got home.”

As the war progressed into 1865, Morey could only speculate on when his service would be fulfilled. In late March he wrote, “I think I would enjoy being home very much if the war was ended and an honorable peace once more established but this little job must be accomplished first….” Just a few days later, Ulysses S. Grant had the Union army lined up in anticipation of shaking the Confederate grip on the city of Petersburg. “We hope and pray that we may be able to strike the death blow to the rebelion before many days but perhaps we may fail,” Morey confided, “yet we hope for the best and will work hard for it and trust in God for the accomplishment of the remainder, now is the time that we need divine assistance, pray for us that we may accomplish all.”

In the early morning darkness on April 2, the 2nd Vermont, and the VI Corps to which it belonged, pierced the Confederate defenses on the grounds now preserved by Pamplin Historical Park. Surrender and the cessation of hostilities lay just one week in the future — but Captain Morey would witness neither. As the VI Corps connected the Union lines west of Petersburg, shrapnel from a battery near Robert E. Lee’s headquarters struck Morey in the head. Thirty minutes later, and just seven days from the end, the wound proved fatal. “It seems a hard fate to perish in the last struggle, after having passed safely through so many,” wrote a fellow Vermonter.

Morey’s remains now rest in Poplar Grove National Cemetery, in a rare, marked grave among thousands of unknown soldiers. To Charles Morey and all who fought alongside or against him, the war’s outcome would remain a mystery, but their legacy continues to inspire new generations of Americans.