By Sharon Denmark

The three million soldiers who served in the Civil War each represent a unique story waiting to be told. Although no two men had the exact same journey into the army, experience in battle or emotional response to their involvement, similar threads weave their way through a significant number of these narratives.

In studying the Civil War’s common soldier — who he was and how the conflict transformed his life — we try to better understand the millions of men who risked their lives in virtual anonymity. What motivated the former innkeeper ordered to charge across open ground in the face of relentless gunfire? How did the factory worker who defended his trench line until the bitter end fare when he returned home with no more record of service than his name scrawled in a ledger? When we study the lives of men like these we gain insights into the courage and sacrifice demonstrated by each and every Civil War soldier. Time and again, they were asked to perform tasks that would have been unthinkable in their past lives as farmers, teachers, lawyers, shop owners, carpenters or iron-workers.

Although enlistment, medical and other official records can sometimes be spotty, they nonetheless allow us to analyze an astounding array of facts and figures to better comprehend an overwhelmingly destructive war. These dry documents, however, are augmented by a huge amount of correspondence, diaries and memoirs. Statistics can tell us something about the men in the ranks, but, thanks to a relatively literate society and the Victorian penchant for personal writing, we are lucky to have these first-person narratives as a pathway into the lives of individual soldiers. The three million soldiers who served in the Civil War each represent a unique story waiting to be told. Although no two men had the exact same journey into the army, experience in battle or emotional response to their involvement, similar threads weave their way through a significant number of these narratives. Thus, as we examine the life of the common soldier, we do so through lenses of both commonality and individualism.

A soldier in the Union army was most likely a slim young man a little over 5’8” tall with brown hair and blue eyes. He was probably a farmer and a Christian. Precise statistical figures are more difficult for Southern enlistees, but most Confederate soldiers looked a great deal like their Federal counterparts — although they were even more likely to be farmers by trade. The war was largely a young man’s fight — Union enlistment records indicate that more than 2 million soldiers were age 21 or under when they joined the cause — and some estimates place only 10 percent of the Federal force over age 30. There were, of course, cases on either extreme. Older soldiers typically filled more specialized roles or were officers; some teenagers lied about their age and saw front line combat, but many others served in other capacities, notably as musicians.

Recruitment tactics of the era typically raised companies from a single geographic area, meaning these units (and regiments they were combined into) reflected the demographics of those communities, often with a particular ethnicity or occupation predominating the ranks. Other units, especially those raised in urban areas, were remarkably diverse. Robert Watson, a Floridian originally hailing from the Bahamas who served with the Confederate army and, later, the Confederate navy, made this observation about the men with whom he served: “Truly this is a cosmopolitan company, it is composed of Yankees, Crackers, Conchs, Englishmen, Spaniards, Germans, Frenchmen, Italians, Poles, Irishmen, Swedes, Chinese, Portuguese, Brazilians, 1 Rock Scorpion Crusoe; but all are good southern men.” It is the final pronouncement that undoubtedly mattered the most to Watson.

Each of these men, no matter his background, had to make a life-altering decision when the country fractured along fault lines that had long been present. In 1860, the United States was still a relatively young country — an evolving experiment in democracy in which both Northern and Southern states sought to protect their own interests. When discussing the motivations of soldiers we must distinguish soldier attitudes from the ideas their leaders espoused. A soldier’s thoughts were his own and did not necessarily belong to Abraham Lincoln or Jefferson Davis: not every Northerner was an abolitionist, nor every Southerner a slave owner. The reasons an individual might enlist were complicated and shifting, ranging from the purely practical to the highly sentimental. Soldiers identified most strongly with their comrades, their states and their communities — with, perhaps, a few country-sized ideals thrown into the mix. Then, of course, there was the draw of war itself as a path to manhood and glory. For others, the promise of a (somewhat) steady paycheck was reason enough to don a uniform. A soldier with the 36th Wisconsin, Guy C. Taylor, upon hearing from his wife that people at home were questioning his motives for enlistment, told her succinctly: “You can gust tell the folks that if they want to know what made me inlist they can find out by writeing to me.”

The daily struggles and the mundane details of soldier life allow us to relate to these men across a distance of 150 years. The risk of falling ill was highest for new recruits, with each passing year in service affording growing immunity. In his book, Army Life: A Private’s Reminiscences of the Civil War, Theodore Gerrish recalls a time spent too long in camp and writes, “One of the most disastrous features of the gloomy situation was the terrible sickness of the soldiers…men were unused to the climate, the exposure, and the food, so that the whole experience was in direct contrast to their life at home.” Common viruses and infections included typhoid fever, malaria, pneumonia, tuberculosis, pox (both small and chicken), scarlet fever, measles, mumps and whooping cough.

Camp provided a soldier’s first test of survival, especially for men from rural precincts. A Civil War-era encampment was not known for its wide open spaces and fresh air. It took little time for an army to alter a landscape by the sheer mass of its presence. Verdant pastures became a muddy mess in no time under the feet of thousands of soldiers and horses. With little understanding of sanitation, camps were notoriously nasty abodes; lice were rampant, and dysentery, often caused by impure drinking water, killed more men than enemy bullets.

Once enlisted and encamped, a recruit soon learned that his time was no longer his own. Day and night, he was under orders, a shift that required constant practice and discipline. In the course of this process, men learned the particular brand of patience known to soldiers today as “hurry up and wait.” A Civil War soldier would find that modern axiom very familiar. In his work The 1865 Customs of Service for Non-Commissioned Officers and Soldiers, August V. Kautz writes that a soldier “should learn to wait: a soldier’s life is made up in waiting for the critical moments.”

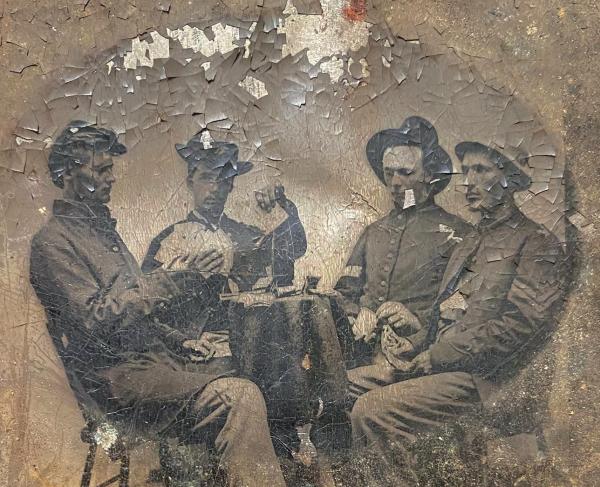

The soldier spent a majority of his time in camp drilling, with the occasional stint at guard duty or a long march. The diaries of Robert Watson document such an existence repeated tens of thousands of times in both North and South: “Drilled in the afternoon….Inspection of arms.…Commenced drilling.…Drill as usual morning and afternoon…. Drilled and…inspected our arms, quarters, &etc….” Theodore Gerrish writes of his first experiences as a soldier: “It was a most ludicrous march. We had never been drilled….An untrained drum corps furnished us with music; each musician kept different time, and each man in the regiment took a different step….We marched, ran, walked, galloped, and stood still, in our vain endeavors to keep step.” All of this practice and repetition helped soldiers to survive on the battlefield when those “critical moments” arrive.

And those moments arrived year after year, longer than anyone in 1861 could imagine. Noble ideas and grand visions suffer greatly under the weight of bloody warfare, and yet the fighting men on both sides endured as best they could. The common soldiers of the Civil War shared typical weaknesses of the human condition. They were not without fear, panic and indecision. Still, we cannot help but look at their service with admiration and draw lessons and inspiration from their endurance, sacrifice and ideals.