Kearsarge and Alabama

The Confederate commerce raider that cost the Union the most ships and the most money, and provoked the most aggravation, was the CSS Alabama, commanded by Capt. (later Rear Adm.) Raphael Semmes. Built in the Birkenhead shipyards in Liverpool, England (ostensibly for the Turkish navy), and identified simply as Hull No. 290, she went to sea on what was advertised as her trial run on July 28, 1862, and never returned. Instead, she made her way to the Portuguese Azores, where she took on a battery of guns, an international crew and a handful of Confederate naval officers. Re-christened Alabama, she began a two-year odyssey that ravaged Union shipping and raised both alarm and maritime insurance rates all along the Atlantic coast of the United States.

It was not Semmes’s purpose to take prizes; he was no privateer looking for booty. His goal was to do such damage to American merchant commercial shipping that it encouraged antiwar sentiment in the North. Besides, taking prizes would compel him to put prize crews on board his captures, weakening his own crew and depleting his officer corps. Instead, he burned his prizes at sea, only bothering with booty when the cargo could replenish his own larder or ordnance locker. Altogether, Semmes made at least 65 captures; he used four of those vessels as “cartels” to rid himself of accumulated prisoners who did not volunteer to join his crew and burned the rest.

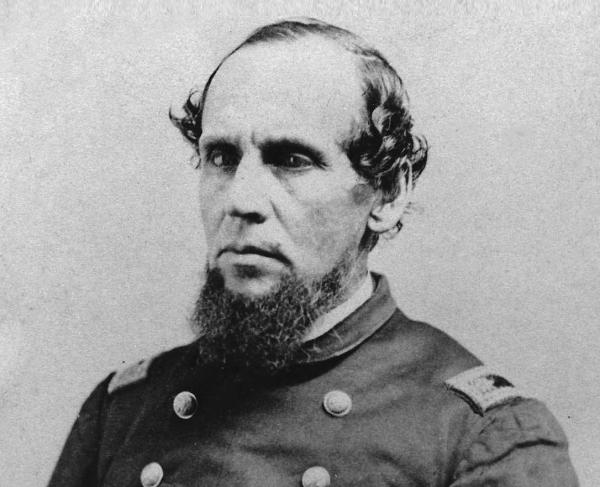

The U.S. Navy tried in vain to track him down — at one point at least a dozen warships were searching for him — but Semmes was illusive, never staying long in one area. He took Alabama across the Atlantic, ranged along the American east coast down to the Gulf of Mexico, then continued south along the Brazilian coast. In the summer of 1863, he re-crossed the Atlantic to Capetown, South Africa, and entered the Indian Ocean. He seemed to have disappeared from the face of the Earth, until he re-emerged in the Sunda Strait between Java and Sumatra and carried the Confederate flag into the South China Sea. Then he cruised back through the Straits of Malacca to India, on to Madagascar and into the Atlantic once again. In the spring of 1864, Semmes made his way north to Cherbourg, France, where he put in for a much needed re-fit. But the USS Kearsarge, commanded by Capt. John A. Winslow, soon arrived off the coast.

To this point, Semmes had faced only one other warship during his amazing odyssey — luring the blockading vessel Hatteras away from her station off Galveston, Texas, and sinking her — concentrating instead on commerce raiding. Now in Cherbourg he had to decide whether to fight or allow his vessel to be interned by the French, as he had done with a previous, smaller command when he found himself cornered in Gibraltar. But Winslow’s Kearsarge was not demonstrably more powerful than his Alabama, and a victory off the coast of France might have a beneficial impact on the French attitude toward the Confederacy. Whatever his motives, Semmes chose to fight.

Both commanders made careful preparations for the fight, but Winslow possessed two advantages that would prove decisive. First, he draped heavy chains over the side of his wooden ship, then planked over the chains so they were not visible, providing greater protection from Alabama’s heavy shot. Semmes later argued that disguising that the vessel was effectively an ironclad was a dirty Yankee trick. Another advantage Winslow had was that while his powder and shells were relatively fresh, Alabama’s ordnance was at least two years old and its reliability was uncertain.

The duel took place on June 19, 1864, in international waters off the coast of France, although close enough to be visible from shore. The two warships circled one another, firing as fast as the crews could load. The quality of Alabama’s shells proved an even greater defense than Kearsarge’s chain mail armor. Several rounds failed to explode, including a shell that lodged in the sternpost of Kearsarge and almost certainly would have been fatal had it detonated. Instead, it was Alabama that took several hits and began taking on water. Semmes fought her until she sank, then — defiant to the last — threw his sword into the sea and swam to the safety of a nearby British yacht that had come out to watch the excitement.

Winslow returned to the United States a hero and received a promotion to commodore; Semmes made his way back to the Confederacy and was promoted to rear admiral. During the evacuation of Richmond, he led a brigade of infantry, and after the war took to identifying himself as “Raphael Semmes, Admiral and General.” The famed raider influenced world events even after her sinking. Once the war was over, the United States filed claims against Great Britain for allowing the construction of Alabama in her yards, and an international court awarded the government $15.5 million in damages.