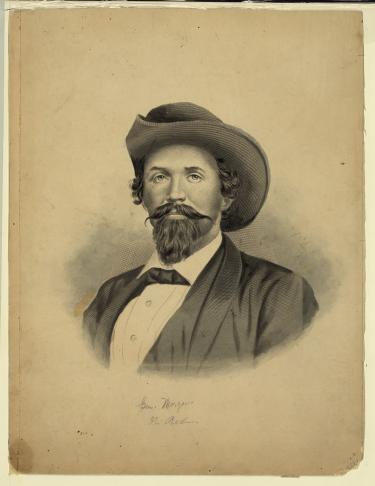

Although never rising above the rank of brigadier general, John Hunt Morgan was one of the Confederacy's most colorful cavaliers and raiders. His exploits took him deep behind federal lines and earned him a reputation for audacity and creativity — even favorable comparisons to Francis Marion, the famed "Swamp Fox" of the Revolutionary War-era South.

Born in Alabama but a Kentuckian since childhood, Morgan did not initially support the Confederate cause in his home state, going so far as to write to his brother that he believed Abraham Lincoln would be a good president. However, as tensions in Kentucky rose and the state government began to splinter under the weight of its faltering, self-imposed neutrality, he began to reconsider his position.

Prior to the war, Morgan was a Lexington businessman who had seen combat as a cavalry private during the 1847 Battle of Buena Vista. Returning home from the Mexican War, he married and reentered private life, although he raised and commanded two companies of militia during the 1850s. In September 1861, following the death of his wife from a protracted illness, Morgan and the majority of his "Lexington Rifles" militia crossed into Tennessee to enlist in the Confederate Army. The band formed the crux of the 2nd Kentucky Cavalry, which fought with distinction at the Battle of Shiloh.

Morgan's first great escapade came in the summer of 1862, when he and 900 cavaliers spent three weeks riding through Kentucky, disrupting the progress of Union forces in the state and raising the hopes of secessionists who sought to bring the state fully into the Confederacy. Morgan and his raiders reportedly captured and paroled 1,200 Union soldiers, acquired several hundred horses and confiscated or destroyed massive amounts of Federal supplies.

An August 1862 edition of Harper's Weekly described Morgan as a "guerrilla, and bandit" with "predatory instincts," and characterized his men as "a band of dare-devil vagabonds" who spent their time "burning bridges, tearing up railway tracks, robbing supply trains, and plundering and wasting the few remaining prosperous portions of Kentucky." The same article, however, also admitted some of the characteristics that gave Morgan a cult of personality in the South — "the most desperate courage" and "some of the chivalrous qualities of his namesake and prototype, Morgan the Buccaneer of the Caribbean Sea" — before noting that these "will not, however save him from being hanged if he falls into the hands of his fellow citizens in Kentucky."

In the summer of 1863, Morgan launched an even more audacious raid through Kentucky, Indiana and Ohio. His inventive and highly successful tactics included having his telegraph operator masquerade as a Union soldier and send false and wildly divergent messages reporting on Morgan's actions, objectives and troop strength, creating confusion and hampering any response. Despite great initial success, Morgan was defeated at the Battle of Buffington Island, Ohio, on July 19, 1863, and some 750 Confederate cavaliers were captured. A few days later, pursued by Federal cavalry, 300 of Morgan's men crossed the swollen Ohio River into West Virginia; the rest continued north and east, hoping for a chance to slip across the river to relative safety. After another defeat at the Battle of Salineville on July 26, Morgan was captured and taken with some of his officers to the Ohio State Penitentiary, while the majority of the enlisted men were sent to Chicago's Camp Douglas as prisoners of war.

In November 1863, Morgan and six others escaped by tunneling out of a cell and scaling the prison walls. Two were recaptured, but the rest returned south, and Morgan recommenced his military exploits. His later raids in Kentucky, with a force inferior to the one he had lost on his great raid resulted in heavy casualties and open pillaging, leading to accusations of banditry. On September 4, 1864, while attempting to escape from a Union raid on Greeneville, Tenn., Morgan was shot and killed.

Although followed breathlessly by the press, Morgan's raid lacks the greater strategic importance of other military events from the summer of 1863, such as fighting at Gettysburg and Vicksburg. Moreover, Morgan conducted his raid in violation of direct orders not to cross the Ohio River, losing him the trust of his superiors and damaging his reputation forever. Still, his results were impressive. He captured and paroled approximately 6,000 Union soldiers, destroyed 34 bridges, disrupted rail lines at 60 sites and diverted tens of thousands of troops from other purposes. In Ohio alone, Morgan's men stole 2,500 horses and raided more than 4,300 homes and businesses. Claims for compensation of losses inflicted by Morgan's men were still being filed into the early 20th century.

Learn More: Guerrilla Warfare