An Interview with Historian Stephen Berry

By Clayton Butler

The Civil War Trust's own Clayton Butler recently had the opportunity to sit down with one the most distinguished scholars in the field of Civil War history – Dr. Stephen Berry of the University of Georgia. He shared his thoughts on the state of current Civil War scholarship and the compelling nature of Civil War history for scholars and the general public alike. As Dr. Berry make clear, the field of Civil War history has only strengthened as it has expanded, and continues to be heir to an extraordinarily rich tradition of first-rate scholarship and research.

Clayton Butler: What do you consider to be the most significant findings or theories generated about the Civil War in the last ten to fifteen years?

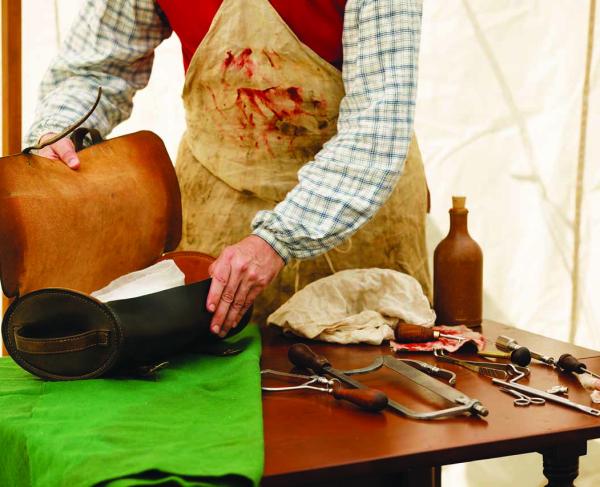

Stephen Berry: Well, historiography is sort of like an ocean liner – it doesn’t tack on a dime; it tends to carry forward. For a while we said ‘well, we don’t want to pay strict attention to the battlefield; we want to study the home front.’ And then we said, ‘well, the home front is related to the battlefield in all of these deep ways’ – it’s a citizen army, with guerrilla warfare etc., so they’re [the battlefield and the home front] much more closely tied – something Sherman certainly understood in making Georgia howl. And now I think we’re getting to a point where we don’t even use these categories anymore. The war is understood as a war of occupation; we better understand that the job that the Union Army had to do was hold and occupy 750,000 square miles. And I think Iraq and Afghanistan have made us appreciate that a bit more. And so I think we’re going to start studying logistics – actually how was the war won [from] supply lines, wheat and fodder and everything else, all of those supply lines are going to be enormously important. That touches on the spatial turn too.

One line that jumped out at me from your piece was, “when you’re fighting a war against yourself, you want to win by as little as possible.”

SB: And I remind students of this when I’m teaching the class, but I actually think the American people don’t quite appreciate that this is a war that evolved, and had to evolve because they’re trying to win it by as little as possible because the more you win it by, the harder it is to put the pieces back together. So you have to apply just pressure enough. And Abraham Lincoln, I think he made more than a handful of mistakes – as anybody does – but one of the major ones was in grossly underestimating just how deadly serious the Confederacy was about fighting this out.

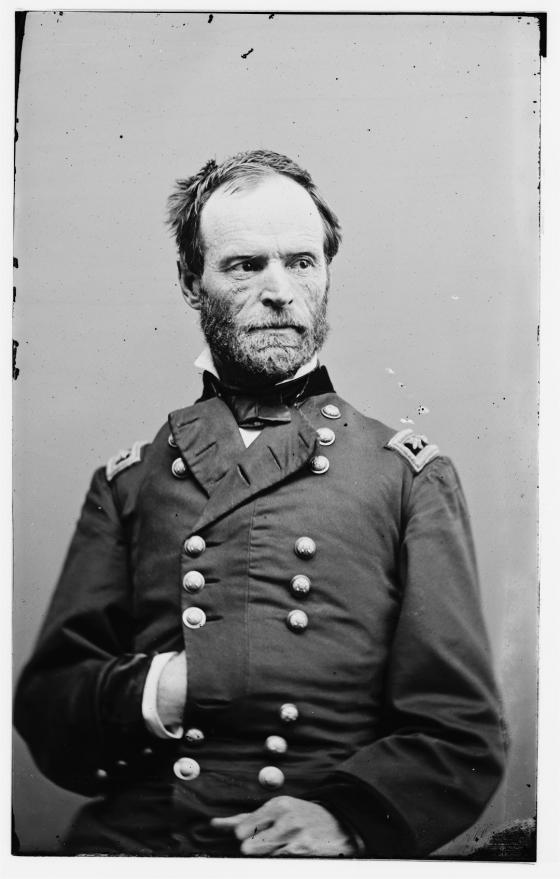

He wasn’t alone in that was he? Sherman was almost forcibly retired because he correctly predicted what was coming.

SB: There were those people who did, and they’re kind of like the Cassandras because they can see it, and they’re almost driven mad by it because no one else can. So I actually see that there was a sizeable minority of people who kind of got what it would mean to have an industrializing nation pick a fight with another industrializing nation. It’s just going to be different than Mexico; different than any other wars we’d participated in before. Once you have a rifled musket as the shoulder weapon of every infantryman it’s a totally different game than we’d seen before.

But to return… I see us pulling back, looking at networks and flows and the notion that the Civil War, as we now understand Columbus and contact, is this massive stir of the biotic soup. All of a sudden people are moving around, so Yael Sternhell’s book [Routes of War] I like quite a bit and she’s saying actually the sine qua non, the common experience of the Civil War, is not actually violence – that’s not what everybody experienced – but they certainly all experienced mobility in a way that they never had before. Soldiers are moving around; people have to evacuate; slaves were never supposed to move and are now on the move as well. And there are consequences to that, including disease, but they’re seeing the country for the first time. I remember being struck by watching Confederate units marching through southern Pennsylvania, which is beautiful farm country, and they’d told themselves so many stories about what the North was, and what a superior country they lived in [with its] superior farms and all of sudden they’re looking at these barns busting with hay and it’s bucolic and beautiful and it seems like a farmer’s paradise. That’s the way they would scan that landscape with the eye. I find that fascinating.

And you’ve also got vice versa, with Northern soldiers going down South and seeing slavery with their own eyes.

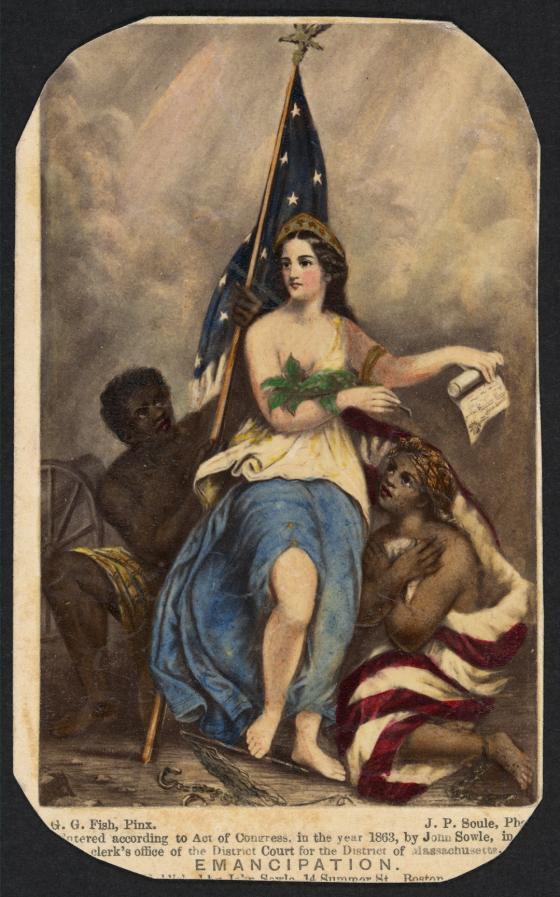

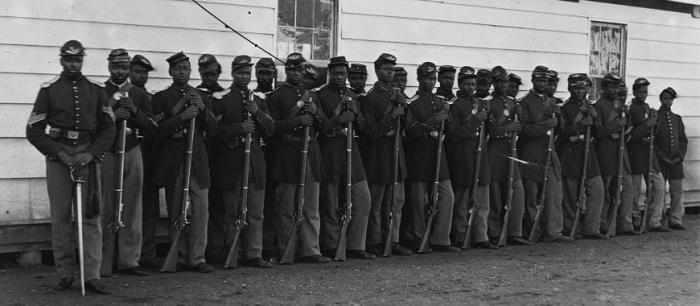

SB: Right, and I think Chandra Manning’s book[, What This Cruel War Was Over, illustrates that] the Union Army is essentially abolitionized on the ground, starting essentially with privates, for whom slaves greeting them; giving them information; giving them food; helping them out; digging the ditches, they’re the only faces anywhere that are happy to see them. And then it just goes up the chain of command until it becomes the concern of the President and Congress and everybody else. So the notion [is] of a Union Army that’s abolitionized from the bottom up, and it’s actually Union society’s opinion that changes last. There’s a fantastic editorial in late 1864, where the New York Times is basically saying ‘we never even considered the possibility of emancipating everybody all at once, and that’s now generally what people assume is going to happen!’

And so, I think, the Civil War is worth studying because it is this moment when time becomes elastic; there’re possibilities for alternate futures. So I see more and more historians not studying the war, and only the war and only those four years, but taking the war in a much broader chronological context. You can’t study the gravity of a thing from inside. You have to throw something into it and see how it’s warped and comes out the other side. I think you’re going to see a lot of people looking 1840 to 1890, things like that. How do these two things connect up after the war? I think people are going broader, bigger, less military. And when they do military, it is a war of occupation. Emancipation is part of the military picture. Glenn Brasher’s book I think is really good on that.

I think people who come at it with comparative perspectives, I think there will be a lot more of that. The notion that this is, somehow, a special war that we’ve sort of clung to, and it’s this crucible that fires the nation and makes us who we are – some of that is true, but it doesn’t open it up to historical analysis very well. In fact, it tends to close it down as being this special thing, we only study these four years, we are scholars and specialists only of it. I just don’t think, at least in the academy, that’s true anymore.

I actually think the historiography is as healthy as it’s been, since the social historians and the military historians have met in the middle and agreed that they each had an important point. So the social historians rightly noted that this is actually two societies who went to war. And especially in an industrializing world, what makes war – what makes war in a democracy--is political will; so what you’re making war on at the end of the day is not an army, but the people at home who say ‘we are going to keep fighting.’ That’s how it works in a democracy [because the citizens] are also making the uniforms; they’re also making the food; they’re also making the buttons and the coffee, arms and armaments and everything else. That’s what makes the Civil War the first modern war, these two industrializing societies. So to think that this is two armies making war on each other is ridiculous. That's maybe was the way war was fought once, maybe. But it’s definitely not true by the time of the Civil War. So the social historians pointed that out, and they were absolutely right.

I also think [that] to teach a course on the Civil War without mentioning any battles is crazy too, because at the end of the day battles matter. And to go back to the point we started with, recognizing that the war evolves matters a great deal, and you cannot in one class capture the evolution of a war that begins sort of as a police action with ninety-day men and then becomes a limited war, and then becomes a hard war, and then finally a hard war on civilians in many ways. And that evolution is the story of how the war is won.

So if you skip the war, you skip that transformation.

SB: Right. And if you only focus on the war you forget that what is really at stake here is a 3.5 billion dollar interest, and no 3.5 billion dollar interest in the history of man has given itself up without a fight. And if you are just appreciating how two armies come at each other, you tend to lose sight of that essential fact. So, in my experience, the social historians made a great point and carried the day, and the military historians have actually made some good points and carried the day too. I feel like we’ve never gotten along better. The health of the field during the sesquicentennial – forget for a moment the kind of programming that is going on or how the public is perceiving the Civil War – within the academy I don’t think the historiography on the Civil War has ever been healthier. The Journal of the Civil War Era right? Understanding this is an era; understanding that Gettysburg is a Civil War battle but so are Hamburg and Colfax. I think we all really get it; the society of Civil War historians has never been stronger. Among graduate students this is a really hot field. A Civil War historian used to be understood as a military historian, now this is somebody who is working on capitalism; who’s working on emancipation; who’s working on environment; working on spatial. I don’t think I’ve ever been as optimistic about my field. So that’s a great thing to have at the sesquicentennial in some ways – that we’re so healthy in academia. I don’t know that I would say the same of the public at large. As I’ve said, soon enough we will understand the war as a test this country failed. Because we couldn’t, short of war, give up the 3.5 billion dollar interest that was bad for America.

We were certainly not the only country with slavery, but we are the only one that fought a war to end it.

SB: And what is interesting to compare, and I think more people are doing this kind of work, is where you have, essentially, manumission/emancipation from the top, controlled by the elites. It’s a very gradual process as compared to America, where it ended violently and the attempt is made to bring former slaves in with full rights of citizens. [If] you look in any other post-emancipation context you just don’t see that attempt made.

You touched on it a moment ago… What do you make of the sesquicentennial commemorations so far?

SB: I think healthy in some ways. So, the centennial happening as it did (this is an interesting moment to be talking about this), Martin Luther King is making his speech at the Lincoln Memorial at the same time as they’re commemorating the war without recognizing that it was about black rights; about emancipation; that the United States Colored Troops were ten percent of the Union Army; that Lincoln himself said they turned the tide of the war [and] without them we couldn’t have won. None of that was being recognized, so there was just this disjuncture between the war as we understand it now and how it was being presented. So I think you have a much healthier presentation of the Civil War now, but because it’s darker and harder to deal with, harder to consume, I think the American public at large is, not losing interest but it’s not something to celebrate. So it’s something to understand but not something to celebrate; so I think the tenor of the sesquicentennial is appropriately different. It’s an ambivalence. The right side won, but the fact that we had to go through all that – what does that say about us as a country? It’s not a note of congratulation.

Is there a particular trend or narrative out there in Civil War scholarship that you disagree with that disturbs you because of its popularity?

SB: I wouldn’t call it a trend, per se – I wouldn’t give it enough dignity to be that, but this notion of high numbers of African-Americans who fought for the Confederacy. There are some myths that I think the internet makes un-killable, because the internet has the illusion of authority for some people, and that one can drive me absolutely crazy. Because it props up this notion that the war is somehow not fundamentally about slavery, and I tell my students basically – to be perfectly clear, on day one – if you don’t think that the Civil War is at root about slavery well then there’s the Flat Earth Society, who will be taking members. There’re people who think we faked the moon landing. I just want you to know where you are. I tell them if you want to believe that, and you want to hold onto that, then you don’t want to sit through this class. Because I’m not only right but my argument is going to carry the day at the end of this class, so if you want to keep that illusion you better get out!

There’s not a serious scholar in America who thinks any of that. I don’t know if there are other parts of the historiography that I fundamentally disagree with. I do think the question of enslaved African-Americans traveling with the Confederate Army, and the roles – forced roles – that they played. That’s starting to get some good attention, and has needed it, because they’re definitely a military asset for the Confederacy. Glenn Brasher’s book is good on this, and Jaime Martinez has written a book about this. I guess that’s part of my point about how healthy the historiography is. To me, there don’t seem to be these kinds of burning debates now. We’re mostly in agreement on the broad strokes, and having a great deal of fun fleshing out these new areas.

Do you have a favorite battlefield?

SB: I’ve been to Gettysburg the most. I took my son there when he was one, just to take his picture and say ‘we’ve been here before’ when I take him back again. Just because it’s utterly beautiful. Antietam, Shiloh I love and for different reasons. Perryville is one of these forgotten ones, which is too bad. When we do that one in class the students are really into it maybe because they haven’t heard as much about it. I should say Fredericksburg too. We’ve had quite a few of our students come through the Park Service, and it seems like a lot of them had worked at Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania.

I am actually sort of a western theater guy, in the sense that I do actually think the war was won and lost in the state of Georgia. I say that in part because I’m here, I’m sure, but when the major western army is watering its horses in the Atlantic Ocean, I think it’s a bit of game over. So the story of the Civil War, to me, is an improbable stalemate in the Virginia Theater, mostly because Robert E. Lee’s Army – while its purposes are awful – one of the greatest military machines that’s ever been. It’s very good at its bloody business, so you have essentially a stalemate there and meanwhile what’s happening in the West – not enough attention was focused on it then, even though Lincoln’s kicking and screaming and saying ‘I’m from Kentucky and I can see’ and ‘Don’t you see, we are winning.’ And it’s all about avenues of advance, right? Here’s where Gallagher’s at his best – the Union Army rolls up 50,000 square miles in the spring of 1862 on the waterways. And then it runs out of avenues of advance, and then the whole game is getting Chattanooga, reinforcing it enough and getting that juggernaut moving again. And once they do, the war is essentially won and lost in the stretch of land that runs from Chattanooga to Atlanta to the Sea.

I sometimes call the Atlanta and Savannah campaigns the Hiroshima and Nagasaki of the Civil War, because they’re making Georgia howl; they’re taking it to the civilians and they’re proving you’re losing. Jason Phillip’s book Diehard Rebels is really good because he looks at the information that’s actually available to people who are on the line in the Confederacy, where rumor and disinformation and a lack of information and a lack of newspapers mean they don’t know they’re losing. And Sherman actually says that specifically, about what he’s trying to do. He’s not only making war on what makes war in a democracy, which is political will, by trying to eat into Confederate morale by decimating the home front. But I think he also has the notion that ‘I have to make you understand: we’re winning. [This is] what losing feels like. I can go wherever I want, and you can’t do anything about it.’ And I think by the time he gets done Georgia is just flat defeated. But it always seems to me that Grant’s solution is worse if you’re a Confederate household. Would you rather somebody sack your smokehouse and take everything or kill your son? Because that is what Grant is trying to do. And your son is irreplaceable.

You’ve called the Civil War a "pool of sadness" that the nation sees itself reflected in.

SB: And I think it serves to humble us. So, instead of saying ‘what a great nation we are; what a magnificent war’ it should be ‘what a great nation we are and remember we don’t always do great things.’ That’s this notion of a more perfect union, the idea that we’re in process and that part of that process is, or, the role of a historian is, to encourage us to live up to our best selves—not to cajole or criticize necessarily but just to remind, that we’ve made mistakes and we’ve fallen down and learned how to pick ourselves back up and move forward. I think Lincoln is the great apostle of that part of the Civil War experience - the humility.

Did you always know you wanted to be an academic?

SB: When I was maybe in first grade or second grade I wanted to be an Egyptologist. The King Tut exhibit came through, I remember that. I liked old things. They had gravity. They seemed to have survived something, so they had wisdom; they had something to teach. Mortality was something I understood really early. So the dead had done something we hadn’t – they’d died. So they had this capacity to teach us how to live; what mistakes not to make; what traditions to carry forward. I was always interested in the dead, and history through that. I never thought about a career as an historian until I went to college. I thought about archaeology, I thought about anthropology. I knew the past was interesting, but there are a number of ways to examine the past. It’s got to be the way you’re wired.

I noticed that on your personal website, there’s a great quote by Robert Penn Warren: “Historical sense and poetic sense should not, in the end, be contradictory, for if poetry is the little myth we make, history is the big myth we live, and in our living, constantly remake.” There’s a theme of the storytelling element of history in your work, can you talk about that?

SB: History is a big umbrella, and I think we can all fit under it, and so I think there are a lot of ways to examine the past. There are some historians who are more inclined to put history in the social sciences, and who are more inclined to look at the past as this sort of laboratory where we can figure out how things work. So if I go take this data set from the 1860s or the 1960s and I put it through whatever machinations and I come out with this hypothesis – then I can apply it to today. And I don’t have a problem with that kind of history, but I don’t do that kind of history at all. Mark Twain has that great quote: “the past may not repeat itself but it rhymes.” And it’s sort of the rhyme that I like. So I put history firmly not in the social sciences but in the humanities. History is a place to study what it means to be human – the great tragedy and the occasional moments of grace. How we fall down; how we learn to pick ourselves up. Why we should be humble; how we’re connected to this project that is so much bigger than us. So I come at it this way – history is my religion; the archive is my church. So it is a much more humanistic enterprise than a social science. So that quote, because it has the poetry in it and because it has this [sense of ] the great project of human being – it’s almost an existential quest, right? To figure out who we are and why we’re here? And we do that through history. And that connects back to the Civil War as this ‘pool of sadness’ when these massive accidents happen in history, a bloodletting that didn’t need to be. I sit there and I study that for a long while because our humanity is very much in there – how we react to these things.

I think that’s the kind of historian I am, but I don’t expect, and I don’t think it would be a good idea, if every historian was that kind of historian.

What work of yours are you most proud of?

SB: It’s kind of funny. I wrote a piece for the Georgia Historical Quarterly that was my first piece that I’d written as a professional historian and it was about the Thomas Butler King family. Thomas Butler King was an absentee father, planter. He was just gone a lot – sometimes in Congress or agitating for a railroad – and his wife is back on the plantation, literally on an island, and the sons are all waiting around for dad to do something for them and then they go off to college and don’t know quite what to do. It’s all just a very rudderless, sad family. And St. Simons, if you’ve ever been there, is just beautiful. It’s got the Spanish moss and the mist is constantly rolling in and it just seems like this weird little gossamer world. And I just wrote that piece so close to the records and didn’t really try to make a historiographical point. But I like reading it because I think I got them.

Stephen Berry is the Associate Professor and Gregory Chair in the Civil War Era and Co-Director, Center for Virtual History at the University of Georgia. Berry earned his master's and doctoral degrees from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and his undergraduate degree in history from Rollins College. He has written several renowned books on the Civil War such as All That Makes a Man: Love & Ambition in the Civil War South (Oxford University Press, 2003), Princes of Cotton: Four Diaries of Young Men in the South, 1848‐1860 (UGA Press and the Southern Texts Society, 2007) and Weirding the War: Stories from the Civil War's Ragged Edges (2011, UGA Press). In addition to authoring several articles in scholarly journals, such as his most recent article "The Future of Civil War Era Studies" in The Journal of the Civil War Era (2012), Berry has also written for magazines such as Civil War Monitor and North and South and is a Distinguished Lecturer in the Organization of American Historians.