Historical Significance of Horse Island

Constance Barone, Site Manager at Sackets Harbor Battlefield State Historic Site, weighs in on the history of the land Campaign 1776 (now known as the Revolutionary War Trust, a division of the American Battlefield Trust) worked to save at Sackets Harbor.

Introduction

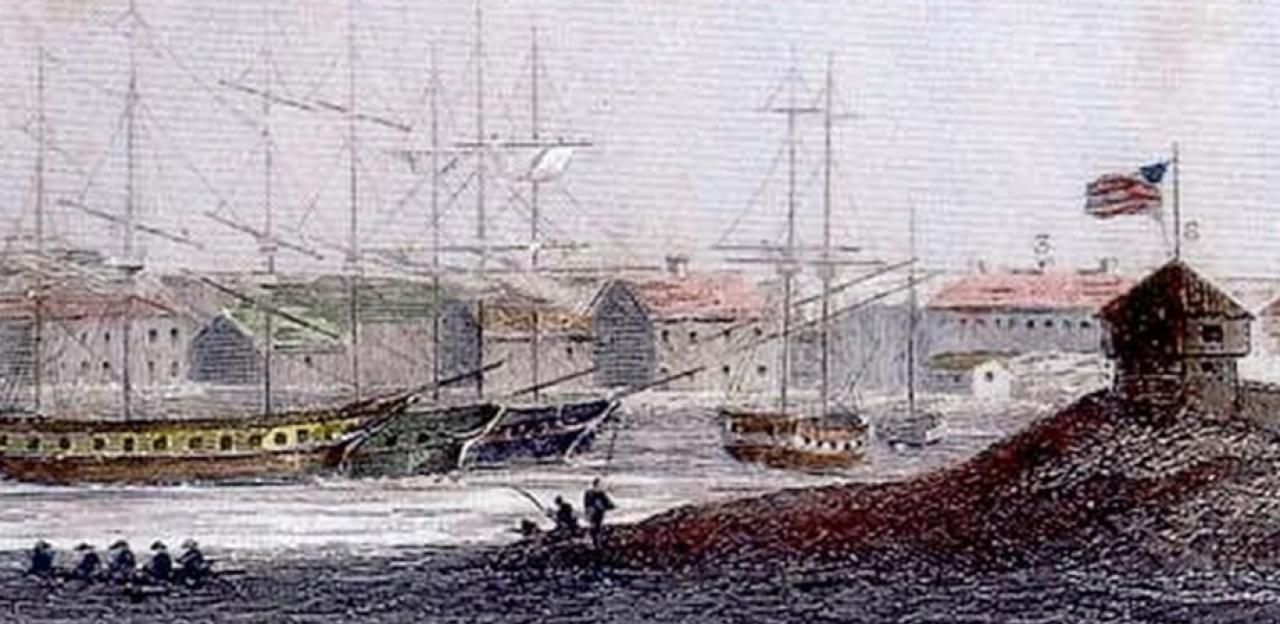

Leading up to the 29 May 1813 Battle of Sackets Harbor was the American defensive posture based on the assumption that the British would have to disembark from their vessels on Horse Island, just one mile west of the harbor, and traverse the approximately 300 yards long submerged narrow causeway of boulders, lake-worn stones and sand, that connected the island to the mainland. The island provided the only practical landing spot as the natural limestone cliffs fronting Black River Bay at the harbor protected the naval yard. In addition, the two American forts at the harbor’s entrance would provide stiff resistance to a direct assault.

To defend the 24 acre “egg-shaped” island, the Albany Volunteers under Colonel John Mills established “Camp Volunteer.” A small 6-pounder provided artillery support of the 160 or so troops on the island. According to the Voltigeurs Canadians Lieutenant Jacque Viger’s map of 1834, the Volunteers camped toward the northeast side of the island, the more likely point of the British landing. The map indicated the British/Canadian disembarking point on Horse Island and the Volunteer’s camp. The island and mainland are depicted as mainly wooded or brushy.

During the night before the attack, NYS Militia General Jacob Brown visited “Camp Volunteer.” Fearing a night attack, he ordered the men to withdraw from the island and join his militia on the mainland as soon as an attack began.

The Landing

Before dawn (3:30am or 4:30am) on 29 May, the British 33 troop-laden bateaux moved toward Horse Island, precisely as the Americans had anticipated. Captain Mulcaster’s gunboats were at the lead to provide a covering fire for the amphibious assault. They were given a warm reception.

According to Viger, "We were advancing slowly and with little noise along the canal which divides Horse Island from the mainland, thinking about taking the enemy by surprise! - when, perfectly awake and on guard, we found it scattered over the two shores and posted behind the trees which border them. It is from there that he sounded the alarm for the rest of the garrison by firing one of the loudest musket shots. Soon the fort batteries joined two field pieces set up like a barbette on the bank, also aimed their cannon balls at our ships.”

The volley that greeted the landing force convinced them to change direction and they moved around behind Horse Island where they were screened for a time from the artillery and most of the musket fire.

Viger, wrote “the obstinate enemy resistance…had to yield finally to the bravery of our sailors and abandoned the Island.” The US Col. John Mills was killed by grape shot from one of Mulcaster’s gunboats and a considerable portion of American killed and wounded received their wounds in the same quarter. The Americans quickly relinquished Horse Island as the Volunteers pulled back from their exposed station. By this time the British were able to land on Horse Island and began to push a landing on the mainland.

Balthazar Kramer, with the Albany Volunteers wrote to his wife, "… we Retreated Of the Iland and formd for battle and in a few moments the Cam up to us and we fought them with grate Spirit lost ower Curnell Capt Collins shot throw the left Shoulder we Retreated and to the woods a small streake between horse Iland and harber and formd and fought till we was Oblidge to Retreate again we Retreated a peas and formd again was Obligd to Retreat to harber and ther we formd wit the Regulars…"

The British units came ashore under fire from the American’s 32-pounder located a mile away at Fort Tompkins and facing the militia under the eye of N.Y.S. Militia General Jacob Brown and volunteers, but they broke after firing their volley early and retreated with rapidity.

There was an American 6-pounder as well, reported: “directly in front of column approaching from the island, and all was silent . . . except this 6-pounder, the enemy approaching and keeping up as heavy a fire as possible from their boats – not a shot was fired from their column, the front approached charging bayonets . . They rushed forward without firing a shot, absorbing a volley when they were “pretty near” and put the militia to flight, the volunteers were also forced back, losing their field piece.

Many years later, a first-hand account by militiaman Jesse Woodward possibly exaggerated his experience on the morning of the attack. He had been detailed to harass the British on their crossing from Horse Island to the mainland. Concealed behind a log, Jesse discovered he was the only militiaman left opposing the British landing force. “I made more ground in less time than any man who ever lived in Northern New York. I thought I was doing my best when a bullet tore up the sod under my feet, then I found out I could let out another link and you can bet I done it.”

The Retreat

As the battle then raged for about three hours, Voltigeurs surgeon Dr. Toussaint Casmir Truteau tended the Crown Forces wounded and dying. At their initial landing site on Horse Island he even had his ambulance, probably a spring-less “hospital wagon,” also called a flying machine or “volantes.” Viger also delivered a wounded man to the doctor. Afterward, Truteau helped load the wounded onto boats for the return to Kingston, Upper Canada.

During that retreat, the invading troops pillaged “Camp Volunteer” with tents full of arms and baggage as well as “some excellent whiskey which they quickly drank to quench their parched throats and gain fortitude.” But, in their haste they accidentally or purposely dropped or threw away equipment to lighten their load in the water. They took one of the abandoned brass six-pounders.

As Crown Forces withdrew around nine in the morning, Viger with the Voltigeurs waded into the water to reach boats nearby, while others with Major Hariot found only Indian birch canoes available. From the deck of the US Pert, Lieutenant Adams could observe the British bateaux full of men leaving Horse Island.

Aftermath

Over the next two hundred years, despite changes and improvements to the facilities at Sackets Harbor in and around the harbor, there appears to have been little in the way of major improvements on Horse Island where a significant portion of the battle was fought.

Horse Island remained largely undeveloped and undefended after the spring of 1813. This is partially evidenced on a ca. 1814 map attributed to Daniel Rose. Aside from sentinels or foot soldiers the island had no formal defenses.

To the southwest of the village near Horse Island, the land was prized agricultural fields. In 1831, however, after a more lasting peace had been achieved, a lighthouse was built on the island with a beacon which could be seen 13 miles away. That lighthouse was subsequently replaced in 1869-70 and it too was surpassed by a skeleton tower in 1956-57. In 1926 the lake water level was so low, that vehicles could be driven across the causeway to-and-from the island.

During the 29 May 1813 conflict, Captain Samuel Mc Nitt served with the militia and became the lighthouse keeper in 1835. Of the several lighthouse keepers over the years, Mrs. Simmons served in the early 1930s. The island was sold in December 1958 by the General Services Administration. At that time a bird sanctuary was proposed.

Summary

Since May 1813, the battlegrounds have been altered by various historical and modern developments. On Horse Island construction of the lighthouse, light tower, and look-out tower disturbed portions of the site. Otherwise, the island remained largely intact.

Today, the island serves as a summer residence and rental property for duck hunters and other sportsmen. The island is accessible over the causeway by amphibious vehicle when the water is low or by boat when the level rises. Trees and brush obscure most of the topography of the island from the mainland. The lighthouse as a seasonal home is the greatest disturbance to Horse Island.