Here Comes the Cavalry

Over the course of nearly a century, through the American Revolution, War of 1812 and the Civil War, cavalry in America faced similar difficulties and shared many facets. Logistics, along with cost and supply demands tended to plague the arm, regardless of the conflict. Volunteers and Regulars were forced to adapt to this, as well as changing technology which transformed their role on the battlefield. Still, the mounted arm had an important part struggles of the young Nation.

At the opening of the American Revolution, the Continental Congress balked at the idea of establishing cavalry regiments, put off by the cost to raise and equip them. Additionally, the terrain of New England, which witnessed the opening phase of the war and consisted of heavy woods, sometimes frozen rivers, and unforgiving mountains, was not conducive to mounted operations. Nevertheless, colonial militia units from Connecticut, New York, Pennsylvania and Virginia formed the ranks of George Washington’s army.

Captain Samuel Morris’s Philadelphia City Troop of Light Horse was prominent in Washington’s New Jersey offensives. They acted as the Commander-in-Chief’s personal escort on the march to Trenton and covered the army’s retreat after the engagement. Eight days later at the Battle of Princeton, the Philadelphians kept a Continental battery from being captured by British cavalry. The Troop later formed the nucleus of the 6th Pennsylvania Cavalry which served in the Army of the Potomac.

The loss of New York prompted Congress to augment Washington’s army with four regiments of Continental Dragoons, which historically meant mounted infantry that would dismount to fight, early in 1777. The units functioned more like European hussars, however. Armed with sabers, pistols, and occasionally a carbine musket, these light cavalrymen excelled at reconnaissance and screening infantry movements, but they could also mount assaults at critical moments on the battlefield to create terror in the enemy ranks and pursue a broken opposing force. However, disciplined infantry, especially those with fixed bayonets, could easily repel a cavalry charge since even the best-trained horses would rather stop in their tracks and cause the charge to falter than impale themselves. Therefore, prudent cavalry commanders carefully chose more vulnerable targets, like loosely grouped skirmishers or easily panicked raw recruits.

Cost, along with logistics forced Congress to alter the makeup of the regiments over the next few years. The Dragoons encountered problems not only with filling the ranks but procuring horses and equipment. Such issues prompted the forming of Legions, which consisted of four companies of cavalry supported by four companies of infantry. This force structure was later utilized in the Eastern and Western Theatres by the Confederate army.

Despite these problems and shortcomings, the Continental mounted forces rendered valuable service during the latter stages of the war, specifically in the Southern Theater of the American Revolution. William Washington’s 3rd Continental Light Dragoons played an instrumental role in the in the battles of Cowpens and Guilford Court House. Henry “Light Horse Harry” Lee’s Legion, as well as militia units led by Andrew Pickens, Thomas Sumter and Francis Marion, saw extensive action in Nathaniel Greene’s operations in the southern colonies. Some of these units acted as traditional dragoons, while others served more as mounted infantry. At the end of the conflict, the standing American army was eventually reduced and the Continental Dragoons were mustered out.

Unfortunately, ongoing problems with Great Britain in the first decade of the nineteenth century impelled Congress to authorize a Regiment of United States Light Dragoons. A second regiment was raised prior to the beginning of the War of 1812. Similar to the American Revolution, militia and volunteers supported the Regular units.

A contingent from the First and Second U.S. Light Dragoons helped repulse a British offensive at Sackett’s Harbor on Lake Ontario in the spring of 1813. As part of William Henry Harrison’s Army of the Northwest, Maj. James Ball’s squadron of 2nd U.S. Light Dragoons withstood the British siege of Fort Meigs. A mounted assault by Col. Richard Johnson’s Regiment of Kentucky Mounted Riflemen helped break the British line in Harrison’s victory at the Battle of the Thames that fall. During the Creek War, Col. John Coffee’s Tennessee Mounted Riflemen fought alongside Maj. Gen. Andrew Jackson’s army at Tallushatchee, Talladega and Horseshoe Bend. On January 8, 1815, Coffee’s men held the left of Line Jackson at the Battle of New Orleans.

Congress reduced the ranks of the army again at the close of the war, and the Dragoons disbanded. With the population moving West, President Andrew Jackson approved an authorization for a Regiment of United States Dragoons in March of 1833. Another was created in 1836, followed by a Regiment of Mounted Riflemen a decade later. While the Dragoons assumed their traditional roles, the Riflemen fought solely on foot and used their horses as a means of transportation. Two regiments of cavalry formed in 1855 and a third was instituted shortly after the outbreak of the Civil War.

In August 1861, Congress re-designated the army’s six mounted regiments as cavalry. Even with this small number and facing the possibility of fighting a war in multiple theatres, the Union high command was suspicious of allowing the Northern states to raise cavalry units. Comparable to the War for Independence, the cost incurred to raise these units remained high. Additionally, leadership believed that it would take between two to three years to properly train a cavalry regiment before it was deemed fit for combat.

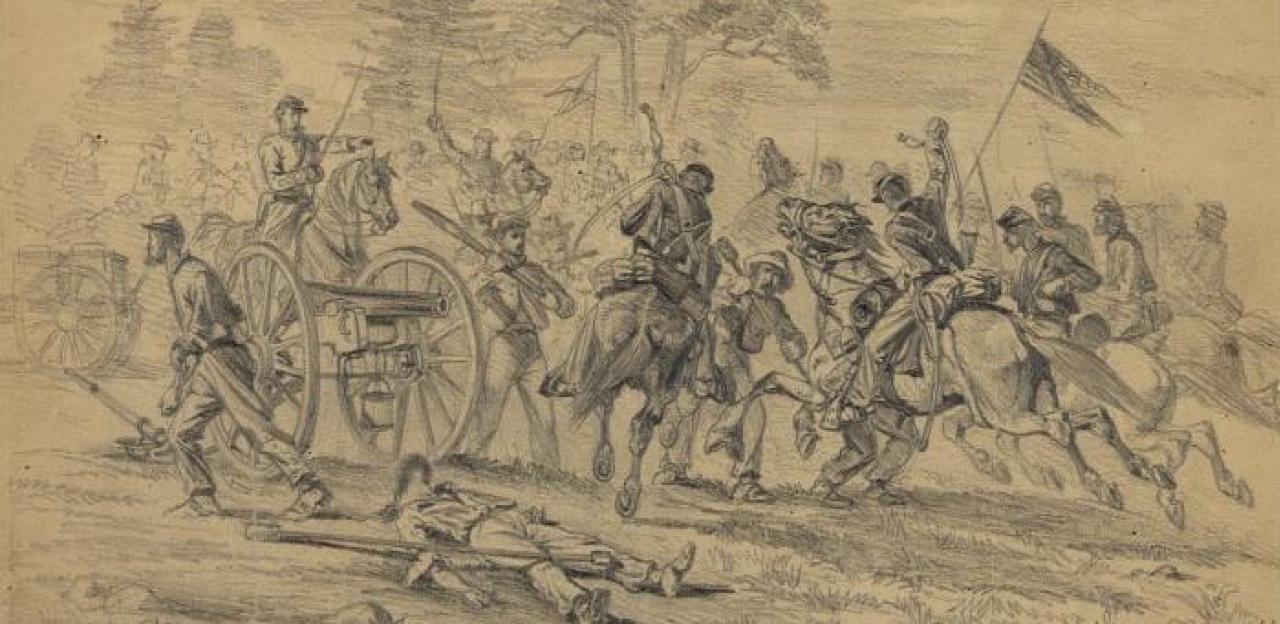

This thought influenced the use of Federal horsemen in Virginia. Although he created standing brigades, Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan, the commander of the Army of the Potomac, parsed his volunteers out to the various corps headquarters to serve as escorts and couriers. It proved disastrous, as James Ewell Brown “Jeb” Stuart’s Confederate horsemen established a decided advantage over their counterparts in 1862. But despite the lack of proper structural support, individual Union regiments performed well. At the Battle of Gaines’ Mill, elements of the former 2nd U.S. Cavalry, reorganized as the 5th U.S., launched a mounted charge which covered the withdrawal of Maj. Gen. Fitz-John Porter’s artillery.

It was not until February 1863, that Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker adopted a model similar to that of the Confederates when he consolidated his mounted arm under one commander who reported directly to army headquarters. This re-organization contributed to the Union cavalry’s later success as they slowly began their ascension to superiority over their enemy.

In July, the Federals took another step forward with the creation of the Cavalry Bureau. Its chief assignment was to work with the Quartermaster Department on the purchasing of equipment and horses. The bureau also oversaw the distribution of mounts along with their subsequent care and recuperation following prolonged duty in the field. No such office existed within the Confederate government, which required its troopers to provide their own horses, which was detrimental to the arm. Once a mount was broken down or killed it was the responsibility of the individual soldier to produce another.

Beginning in 1863, the emergence and issuance of repeating firearms, specifically the Spencer and Henry repeating rifles, impacted the role of the cavalry. It began a transition from the traditional mounted responsibilities of scouting and screening to that of a strike force which fought on foot. This was illustrated by clashes, in 1864, at Haw’s Shop and Trevilian Station between Maj. Gens. Wade Hampton and Philip Sheridan. Major General James Wilson’s cavalry fought dismounted and played a prominent role in the decisive victory at Nashville in December 1864. The following spring, Wilson’s troopers launched a similar attack which captured the industrial center of Selma, Alabama. Even with this marked change, Union cavalry continued to execute assaults on horseback with great success. Mounted charges helped break Confederate positions at the Battles of Yellow Tavern and Third Winchester.

The cavalry arm underwent an evolution between 1776 and the final Confederate surrender. Advances in weaponry had changed its role on the battlefield. The Volunteers and Regulars who served in the ranks witnessed this progress but also had to overcome shortfalls in organization, supply, and logistics. Despite such obstacles, the cavalry emerged victorious in its early wars and stood poised to play a critical role in the final phase of Westward Expansion and beyond to the twentieth century.