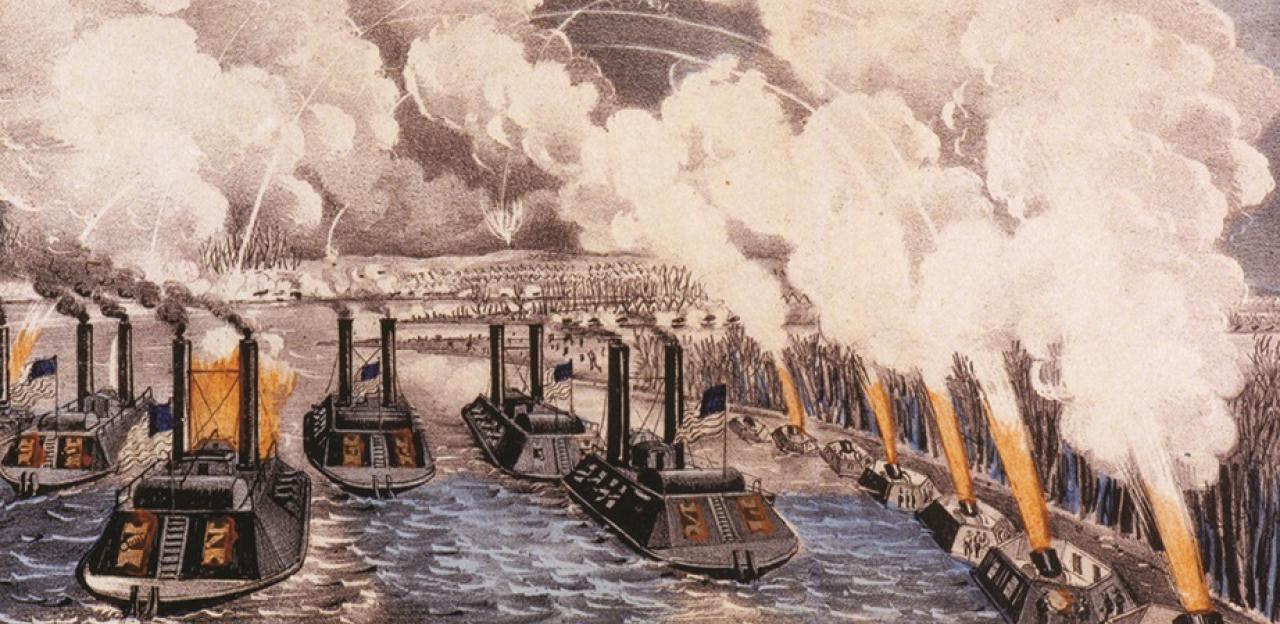

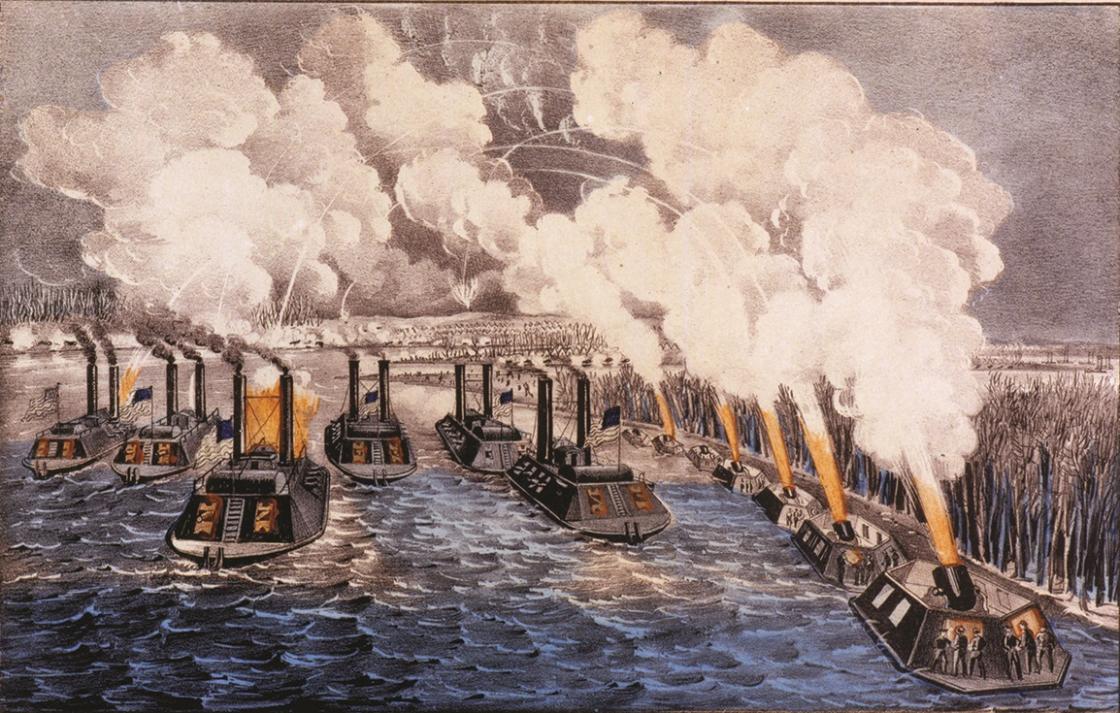

Gunboats on the Mississippi

In addition to prosecuting the coastal blockade and pursuing Confederate commerce raiders, the U.S. Navy’s other main role in the Civil War, and arguably its most important one, was seizing and controlling the Mississippi River and its tributaries. In this effort, the main obstacle was not the tiny Confederate navy, but rather the formidable shore fortifications erected by the Confederates along the banks of the Tennessee, Cumberland and Mississippi Rivers. This war, therefore, was less often a matter of ship vs. ship than it was Union ships vs. Confederate forts.

In these confrontations, the key to eventual Union victory was effective interservice cooperation between the army and navy. Alone against a creative and determined foe, neither service could have achieved the kind of dramatic success they did together. This outcome was all the more remarkable because there was no combined operational command — when army generals and navy flag officers worked together, it was solely a matter of mutual cooperation.

The first important triumph of Union forces against Confederate river forts came at Fort Henry on the Tennessee River on February 6, 1862, when a squadron of armored warships under Flag Officer Andrew H. Foote out-dueled the rebel gunners ashore and compelled the fort’s surrender before army troops under Brig. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant arrived. Ten days later it was the army’s turn to win the laurels as Grant surrounded Fort Donelson on the Cumberland River and dictated terms of “unconditional surrender.”

But at Island Number 10 on the Mississippi River, it was a different story. Here Foote’s gunboats could not take on the heavy shore batteries unassisted, and Maj. Gen. John Pope’s infantry was cut off from the enemy by the river itself. Unless these forces could find a way to work together, the Union advance down the Mississippi would be halted before it fairly began.

What made Island Number 10 so daunting an obstacle was its peculiar geography — a dramatic S turn at the point where the Mississippi River flowed southward from Kentucky into Tennessee. In the first bend sat an island — the 10th one counting southward from where the Ohio flowed into the Mississippi — where the Confederates had erected a series of shore fortifications bolstered by a substantial floating battery.

Unlike at Fort Henry, Foote’s gunboats could not simply pull up alongside and slug it out with the enemy; nor could the army assail the rebel fortifications from the landward side, as Grant had at Fort Donelson, thanks to swampy marsh created where a tributary entered the river. A better line of attack was from the south, but that would be possible only if Pope’s men could cross the river and approach the fort from the rear — a movement that would require the gunboats to pass the island and transport them. Neither Union force could subdue the enemy, or even approach him menacingly, without support and assistance from the other.

Recognizing the situation, Foote and Pope tried to see if they could cut a canal through the marshy swampland of the S curve to bypass Island Number 10 and link up with Pope’s soldiers at New Madrid, Mo., but the gambit proved fruitless. There was nothing for it but for some brave soul to try to run past the Island Number 10 batteries. The man who volunteered to try was Cdr. Henry Walke of USS Carondelet.

On the night of April 4, 1862, Walke attempted to slip past the enemy batteries, but a spark from his ship’s stack alerted the sentries and the Rebels opened fire. Despite facing a gauntlet of fire and the danger of navigating the winding river at night, Carondelet made it safely past the island. Two nights later, the USS Pittsburgh, under Lt. Egbert Thompson, made the same run, and, on April 7, the two ships transferred Pope’s soldiers across the Mississippi to assault the Rebel’s unprotected southern flank.

The geography of the Confederate position at Island Number 10, once its great strength, now proved to be a trap. With Pope cutting off their communications southward, and Foote’s gunboats holding the river above and below the island, the Confederate defenders could do little but accept the inevitable. Pope captured both the fort and its 6,000-man garrison, making him a hero in the North and winning him the command of a field army in Virginia.

Although Foote’s deteriorating health soon compelled him to relinquish command of the Mississippi Squadron, his strategic impact was immense. At Vicksburg almost exactly one year later, Rear Adm. David Dixon Porter and Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant used a nearly identical strategy of army-navy partnership to seal the fate of the citadel on the Mississippi and split the Confederacy in two.