"Life of George Washington - The Farmer" by Junius Stearns shows Washington standing among African-American field workers harvesting grain; Mount Vernon in the background.

The most prominent and dominating feature of the Washington, DC skyline is the 555 foot obelisk known as the Washington Monument. While there are statues of George Washington in traffic circles and other nooks and crannies in the nation’s capital, most Americans, and for that matter, foreigners, acquaint Washington with the towering obelisk. On first glance it may seem odd that America’s foremost founder would simply have an obelisk dedicated to his memory. But the obelisk is symbolic of the Egyptian Sun God, Rah, the giver of light and life. While Washington may not have sired any children he is fittingly called “the father of the United States” for many reasons.

Biographer Thomas Flexner called Washington, “the indispensable man” and historian Joseph Ellis argues that, “Washington was the glue that held the nation together,” a reference not only to his military leadership during the War for Independence, but also for his political leadership at the Constitutional Convention and his moral leadership as First President of the United States. Though well read, as an intellectual Washington did not share the same company with founders Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson, but his leadership skills were peerless. Abigail Adams, an ever astute judge of the human condition wrote:

He has a dignity which forbids familiarity mixed with an easy affability which creates love and reverence… [he] has so happy a faculty of appearing to accommodate and yet carrying his point, that if he was really not the best intentioned men in the world he might be a very dangerous one.

George Washington was at the forefront of every major event of American history from 1754 to 1799. Washington was born in February 1732 to Augustine and Mary Ball Washington. His father died when he was eleven and he was raised principally by his mother and his half-brother, Lawrence, whom he adored. For most of his adolescence and early adulthood he craved fame as well as fortune. His parents were of humble stock, but he wanted more. More important than money, Washington yearned for a commission in the British Army.

As an ambitious ego-centric twenty-one-year-old land surveyor from Virginia’s Northern Neck, when the Empires of France and England both claimed the Ohio River Valley, Washington jumped at the chance to lead a small armed scouting party to the three forks of the Ohio (now near present day Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania) to deliver to French officials there an ultimatum to return to Canada or risk war. He was commissioned a Lieutenant Colonel in the Virginia Militia by Virginia Royal Governor Robert Dinwiddie.

While on the mission, Washington unwittingly triggered the French and Indian War when his party, which also included Indian warriors, stumbled on an encampment of French soldiers, led by the French diplomat Joseph Coulon de Villiers de Jumonville. In the dawn hours of May 28, 1754, Washington rashly decided to attack the French. In the melee he lost control of his Indian Allies, one of whom planted his tomahawk in Jumonville’s head.

Recognizing that a debacle had taken place, Washington returned to Virginia to report to Governor Dinwiddie. Two months later, Washington returned to the area where the May skirmish had taken place, this time with a contingent of 250 Virginia militiamen. In an area dubbed “the Great Meadow,” Washington ordered a crude stockade erected. It was a tactical blunder, as Fort Necessity was surrounded by trees and small hills--all but indefensible.

On July 3, 1754, a combined French and Indian assault, provoked by the Fort’s presence, began. For two days Washington’s command huddled under relentless assault complicated by a driving rain. The next day, ironically, July 4, Washington surrendered his fort. When he signed the terms of surrender, written in French which he could not read, there was a clause that implicated Washington in the “assassination of Jumonville.” The signed confession triggered war between England and France known in North America as the French and Indian War and around the world as the Seven Years War. It was the first global conflict pitting the two great superpowers of the age against one another and would have longstanding implications into the early 19th century.

A year later, in 1755, Washington rode as an aide with British General Edward Braddock’s command to reclaim the contested area of the Ohio Valley. Present with them were men who would cross paths with Washington in the future, including Thomas Gage, William Howe, and John Burgoyne. On July 9, 1755, the French and their Indian allies pounced on Braddock’s force as it neared the Monongahela River. Washington had urged Braddock to send out flankers to cover the army as it meandered through the forest, but for Braddock, Washington was nothing but a provincial whose opinion did not matter. The rebuke and sting would last for Washington’s life.

Surprised in the wilderness, Braddock could not maneuver his army into typical European style battle formation. At the height of the battle, Braddock was cut down. Washington, rode on horseback trying to rally British regulars and the Virginia Militia. His coat was pierced by at least seven bullets. As the Franco-Indian force melted back into the forest, Washington skillfully managed the retreat. Several days later, the gravely wounded Braddock died. Washington had him buried and marched the retreating army over his grave so as to not have the burial site be known to local Indians.

In 1756 Washington travelled to Boston to appeal to British authorities for a command in the British Army. His appeal fell on deaf ears and Washington was bitterly disappointed. It is important to understand that American colonists were proud to be loyal subjects of the Crown, but they bristled at the English attitude that colonists were mere provincials who had achieved status by means of commercial wealth and not birth. For Washington this was an anathema.

Returning to Virginia, Washington settled into the life of a Virginia squire. Upon his half-brother Lawrence’s death, he inherited the family estate built along the banks of the Potomac River near Alexandria, Virginia. To become influential Washington needed money. While his family was not hardscrabble farmers they were not Virginia gentry either. To help solve his dilemma Washington, in 1758, began a courtship with the wealthy widow, Martha Dandridge Custis. That same year he was elected as a representative to the Virginia House of Burgesses, the Virginia colonial assembly. In 1759, he and Martha were married. As was the custom of the day the woman’s dowry went to the man. Thus Washington secured a fortune via his marriage to Martha.

Martha never bore Washington any of his own children. It is suspected that on a trip to Barbados with his half-brother Washington contracted a high fever and lost his ability to reproduce. Washington did, however, upon his marriage adopt Martha’s two children. For many years after Washington’s death and with the ascendancy of the United States it was common to hear, “Washington never fathered any children, but he fathered a nation.”

Using his newfound wealth, Washington moved his new family to Mount Vernon, which he continued to enlarge. He modified the mansion and added many acres all worked by the slaves that had come into his control with his marriage to Martha.

As tensions between the American colonies and Great Britain increased over the next decade, Washington kept his pulse on the tide of the strained relations. He was incensed at what he believed was an overreaching policy of Parliament to directly tax American colonists without representation in that political body. After the Boston Tea Party of December 1773, and the subsequent closing of Boston Harbor by British authorities, Washington was sent as a representative from Virginia to the First Continental Congress in Philadelphia in 1774. He also took a leadership role in his home county of Fairfax Virginia to draft and sign the Fairfax Resolves which expressed displeasure over England’s treatment of the colonies.

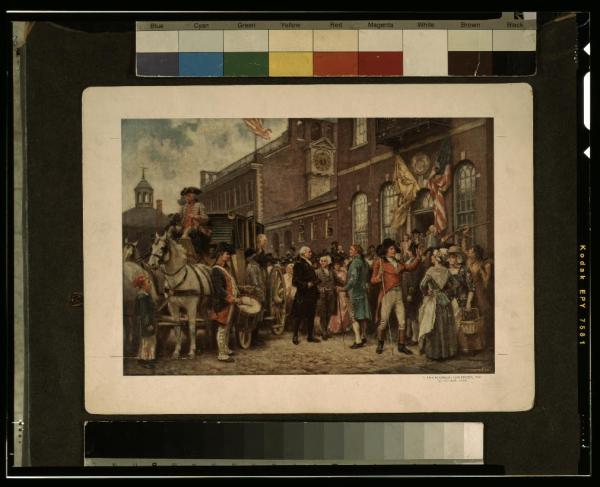

In 1775, he was elected once more as a delegate from Virginia to attend the Second Continental Congress, again meeting in Philadelphia. This time he showed up wearing his old Colonel of the Virginia Militia uniform. Washington could smell a fight coming on and his appearance in military dress symbolized most dramatically that Washington wanted a large role in the coming conflict.

While not an intellectual, Washington was a devotee of theatre. His favorite play was Joseph Addison’s tragedy Cato, the tale of ancient Republican virtues clashing with the imperial rule of Julius Caesar. Washington’s favorite line from the play and one to which he aspired, from Act 1, Scene 2 was, “Tis not in mortals to command success; but we’ll do more Sempronius, we’ll deserve it.”

Much of Washington’s success as a leader can be attributed to his understanding dramatic moments and how to capitalize on them when opportunities presented themselves. He lived by a personal coda, “Study to be what you wish to seem.”

When war broke out in April 1775 at Lexington and Concord, the Second Continental Congress began an earnest effort to provide for the defense of the colonies. When news of the slaughter of British troops on the slopes of Breed’s Hill (Bunker Hill) in June 1775, a Pyrrhic victory for the British, reached Philadelphia, everyone understood the seismic shift. Reconciliation with Great Britain could no longer be possible. Congress girded for all-out war with Great Britain and appointed Washington to assume command and shape an army out of the mob of New England patriots that had bottled up British forces in Boston.

Washington left Philadelphia for Cambridge, Massachusetts where according to local lore he assumed command of the rag-tag force under the spreading branches of a chestnut tree. Washington could be impulsive and he wanted to do nothing more than force a fight with the British General William Howe’s army. Like all great leaders, Washington understood his limitations and selected people to his team who could help him achieve goals. He was always a receptive listener to his advisors.

Invited to join his military family was the self-taught artillerist and Boston bookseller, Henry Knox, and Rhode Island native Nathanael Greene, both of whom would serve the American cause to the end. As time passed Washington invited others to serve on his staff who became important in their own right including Alexander Hamilton and the Marquis de Lafayette, son of a French nobleman. Hamilton and Lafayette in particular developed a close father-son relationship with Washington.

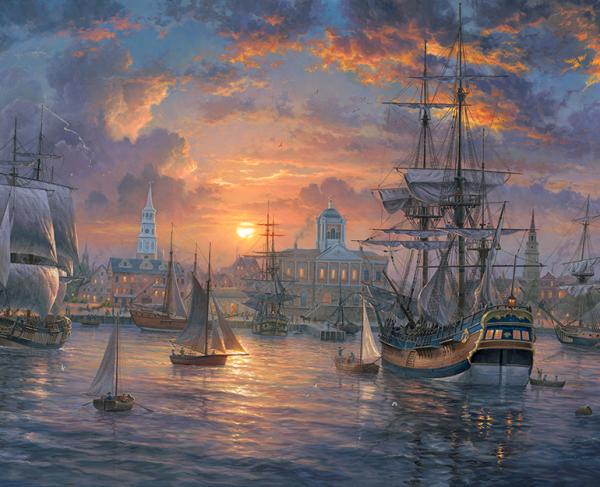

Rather than launch a frontal assault against the British in Boston, Washington accepted Knox’s plan to secure cannons from Fort Ticonderoga in upstate New York, which had fallen into patriot hands in May 1775. During the winter of 1775-1776, Knox’s expedition hauled the much-needed artillery from Fort Ticonderoga under arduous conditions to Boston where they were emplaced around Boston on several points of elevation, most prominently Dorchester Heights, aimed at the British. The tactic worked, forcing the British to evacuate Boston by the end of March 1776, rather than risk another bloody assault on the patriot fortifications.

While not a great tactician on the field, Washington understood the big picture. In the months after the British evacuated Boston, Washington guessed correctly that the Crown’s forces would next attempt to take the City of New York. As the Continental Congress debated colonial independence in Philadelphia during the early summer of 1776, Washington moved the Continental Army south from Boston to fortify New York against an impending British attack. William Howe did not disappoint and in mid-July 1776 a massive force of British troops, augmented with German mercenaries, and under the protection of the naval forces of Howe’s admiral brother, Richard, appeared off of Staten Island.

Congress adopted the Declaration of Independence in early July 1776. Washington received the news at his New York headquarters on July 9, issuing a General Order on the same day for his troops to form up in the “evening on their Respective Parades, at six O'Clock, when the declaration of Congress shewing the grounds and reasons of this measure is to be read with an audible voice.” The Commander of the Continental Army wanted his soldiers to know that they now were part of a new nation. Washington said that “this important Event will serve as a fresh incentive to every officer, and soldier, to act with Fidelity and Courage, as knowing that now the peace and safety of his Country depends (under God) solely on the success of our arms.”

Optimism soon gave way to reality. The new United States had no real government other than the ad hoc one formed by Congress. There was little money, if any, to supply and pay the troops. For much of the war, Washington would be begging Congress for money, men, and supplies. The weaknesses of Congress during the war helped forge in Washington, later as President, and others, the need to have a strong central government at the helm of any nation.

Throughout the summer and fall of 1776, the New York Campaign proved for the Continental Army to be one seeming military disaster after another, from the drubbing British forces handed to Washington on Long Island to the capitulation of Forts Lee and Washington overlooking the heights of the Hudson River. By mid-summer, the British occupied the City of New York after Washington miraculously evacuated his forces from Long Island under the cover of a seemingly providential fog. Howe’s army chased Washington’s rag-tag band across New Jersey, but were never quite able to bag their foe.

By Christmas 1776, Washington’s much-reduced army, wearing threadbare uniforms, many without shoes, huddled along the western banks of the Delaware River in Pennsylvania. Washington needed a win and badly. This time his audacity worked in his favor when he “crossed the Delaware” on Christmas night and led his men on an eight mile forced march to attack the German Hessian barracks at Trenton, New Jersey. Taken by surprise in the early morning assault, the Hessians, many in a panic, surrendered. Not only did Washington take prisoners, but also badly needed food, clothing and supplies. It was the spark the Continental Army and the American people needed.

With morale boosted, Washington next attacked nearby Princeton only days later. It was another stunning victory. In retrospect, these "Ten Days" of campaigning may have been the turning point of the war.

Washington’s genius seemed to be his ability to keep the army together in spite of heavy odds against him. He could inspire men to carry on against formidable opposition and he engendered genuine loyalty among the men in the lowest ranks.

For the remainder of the winter of 1776-77 Washington encamped his army in northern New Jersey, near Morristown, where he could keep his eye on Howe’s forces in New York while keeping the American capital at Philadelphia to his rear.

The campaign of 1777 was equally dismal for the Continental Army. Once more tactical know-how eluded Washington, particularly at the Battle of Brandywine fought in September. With this defeat General Howe’s forces occupied Philadelphia as Congress fled and Washington moved his troops into winter quarters twenty miles northwest of Philadelphia at Valley Forge.

The only bright spot for the Continental Army came in October when American forces in upstate New York led by General Horatio Gates, Benedict Arnold, and Daniel Morgan blunted a British invading force at Saratoga moving south from Canada in an effort to divide New England from the rest of her fellow states. It was a stunning victory, and allowed American operatives Benjamin Franklin and Silas Dean, working in Paris, to convince the French to openly embrace and support American independence. With the deal, money, supplies, and men came to the fledgling American cause.

After Saratoga, Washington had to keep his eyes on two enemies, primarily the British, but also a cadre of officers in his own military family that sought to oust him, led principally by Horatio Gates. Washington was able to ride out the storm due to the loyalty he had built up amongst most of his subordinates and the support of Congress.

The American experience at Valley Forge has become the stuff of legend. Some have called it “the crucible of victory.” Yet it really wasn’t the weather that was the enemy during this period of military inactivity, but rather disease and privation. Washington’s personal burden was slightly alleviated when his wife, Martha, joined him.

Militarily, the Continental Army received a real shot in the arm when the Prussian Army officer Frederic von Steuben arrived at Valley Forge with a letter of introduction from Benjamin Franklin. Washington put von Steuben to work drilling his army in proper drill and fighting technique. Under the watchful eye of von Steuben and with a new discipline the Continental Army began to congeal into the fighting force it had never been.

When the army marched out of Valley Forge in the spring of 1778 there was a perceptible espirit des corps bolstered by new uniforms and weapons supplied by the French allies. The Continental Army now wanted to prove its worth.

Washington, eager to beat the British Army in the field, pursued the rear guard of British General Sir Henry Clinton, who had succeeded William Howe as overall British commander in North America. Clinton opted to evacuate Philadelphia and reoccupy the City of New York. On June 28, 1778 Washington’s forces moved in on Clinton’s army in the vicinity of Monmouth Courthouse, New Jersey.

It was a hot and humid day which saw heavy fighting with men on both sides dropping from the heat. When it was over, the Americans had secured a victory, in the field, against the British. Washington pursued Clinton to the City of New York and for much of the rest of the war Washington and the main portion of the Continental Army kept the British hemmed in the City of New York.

The British, unable to subdue the rebellion in the North, switched their strategy to the South after 1778, hoping that the vast population of American Loyalists would come to the aid of their British brethren. Rather than divide his command, Washington, with a tight rein around New York, shuttled different commanders to head the Continental Army in the Department of the South. After the disastrous defeat of the American Army in the South at Camden, in August 1780 Washington made one of his wisest decisions as Commander of the Continental Army, replacing the disgraced Horatio Gates, who fled from the field of battle at Camden, with one of his most trusted subordinates, Nathanael Greene.

Greene proved to be a wily opponent as he outmaneuvered British General Cornwallis at every turn in the subsequent Southern Campaign. With the help of Daniel Morgan, who gave the British a “devil of a whipping” at the Battle of Cowpens, South Carolina in January 1781, and his own matchless performance in March at Guilford Court House in North Carolina, Greene’s tactics forced Cornwallis to encamp in Virginia along the Chesapeake Bay at Yorktown, to resupply and refit. Instead, it was where the war came to its dramatic climax.

As Greene was having his way with British forces in the South, a pensive Washington kept a wary eye on Clinton’s forces in the City of New York. It was with great joy that Washington in March 1780 received the news that a large French Army had disembarked at Newport, Rhode Island and was moving towards New York to link up with him. Rather than wait for his new allies under the command of General Rochambeau to arrive, Washington, along with Lafayette, rode to Wethersfield, Connecticut to meet him. By 1781, Clinton in New York faced a formidable foe as the Franco-American Alliance came together.

Rochambeau spoke no English and Washington spoke no French. They had to work together through translators. Nevertheless, there was a general sense of ease and sense of purpose in which Washington and Rochambeau worked together. To Rochambeau’s credit, he understood that Washington was the overall commander and he respected that.

In the midst of the joyous arrival of French allies, Washington experienced one of his darkest and most bitterest moments of his tenure as Commander of the Continental Army. He learned that one of his bravest and most able field commanders, the mercurial Benedict Arnold, colluded with the British to turn over to them the strategic American garrison at West Point overlooking the Hudson River. Had the treasonous act not been uncovered, it could have changed the direction of the war. Washington was famous for his temper. It was a trait he spent all his life trying to master.

With the damning evidence of Arnold’s betrayal in hand, Washington took it personally, saying, “Treason of the blackest dye was yesterday discovered!” While not necessarily religious, Washington believed he was always held in “the hands of a good providence” and at times expressed his belief that this “good providence” shined not only on him but on the American cause as well. Such was the case with Arnold’s treachery, with Washington claiming, “In no instance since the commencement of the war has the interposition of providence appeared more conspicuous than in the rescue of the post and garrison at West Point from Arnold’s villainous perfidy.”

Initially Washington suggested a combined Franco-American assault on New York, but Rochambeau skillfully deflected the suggestion. In the meantime, news reached Washington’s headquarters that Greene had maneuvered Cornwallis against the Virginia coast. Washington was even more elated when he learned that a large French fleet was sailing north from the Caribbean to tighten the noose around Cornwallis’ forces. He had long believed that a combined land and naval campaign would be the best way to root the English out from New York, but circumstances dictated otherwise. The time to act in concert had come.

Washington devised a scheme which would keep Clinton sealed in New York while he and Rochambeau’s forces would secretly march south and trap Cornwallis. Leaving a detachment of soldiers to demonstrate on Clinton’s front, Washington and Rochambeau secretly led their forces south from New York to Virginia. On their way Washington stopped at his estate, Mount Vernon. It was the first time he had been back to his home in eight years. While there he entertained his military family as well as Rochambeau and his staff.

When the festivities concluded, the allied forces continued their march south. In mid-September, near Williamsburg, Virginia, they linked up with the forces of Lafayette who had been detached to the Southern Department. As allied forces moved south, the French Navy soundly defeated the British Navy in the crucial Battle of the Capes off the Virginia coast, dashing any hope of Cornwallis for reinforcement and badly needed supplies. The sea lane route of escape and redemption was effectively sealed off.

Holding a council of war, Washington, Rochambeau, and Lafayette decided to lay siege to Cornwallis at Yorktown. The siege began on September 29, with Washington given the privilege and honor of firing the first cannon into the British defense. After almost three weeks of protracted bombardment and two vicious fights for control of British redoubts, Cornwallis asked for terms on October 18, 1781.

Cornwallis’s army surrendered on October 19, 1781. His army was denied by Washington the custom of surrendering with honor, in retaliation for the same treatment that had been given to American forces after the British victory at Charleston, South Carolina. As British troops with flags furled marched between the American and French forces it was hard for them not to note that the French appeared in full military regalia, while soldiers in the Continental Army looked more like an organized band of ragamuffins.

Cornwallis, claiming illness, did not participate, sending in his place his second in command, Charles O’Hara. At first O’Hara offered his sword to Rochambeau, but the Frenchman refused to receive it and directed O’Hara to Washington. Sensing the snub, Washington directed his second in command, Benjamin Lincoln, to take the sword. It was also Lincoln’s forces who had been humiliated by the British at Charleston. With the surrender of Yorktown the military operations of the war virtually ceased, and would not officially be concluded for two more years.

After the victory at Yorktown, Washington moved his army back to New York, and the French sailed home. He took up a position on the west bank of the Hudson River in Newburgh, sixty miles from the City of New York. He remained in Newburgh from April 1782 – August 1783. While at Newburgh Washington continued to struggle with administrative details, particularly those arising from an antagonizing rift that festered between the army and Congress. Neither soldiers in the line nor officers had been paid. Their patience with the ineffective legislature grew thin. Washington could empathize with them writing, “The Army, as usual, are without pay; and a great part of the soldiery without shirts; and tho’ the patience of them is equally thred bear, the States seem perfectly indifferent to their cries.” There was speculation that now that the British were leaving, Washington would appoint himself monarch and seize the new nation via military dictatorship.

An anonymous circular was printed and distributed calling for the officers to “to redress their grievances” at a meeting on March 11, 1783. Washington was not invited to the meeting but learned about it as rumors leaked. On the 11th he issued a General Order that no such meeting be held, but he agreed to meet with his disgruntled officers on March 15. He would give his officers an opportunity to vent their frustrations and be heard. The officer corps considered sending an ultimatum to Congress: to pay their debts or face an armed insurrection by the army or the relocation of the army to “some unsettled country,” whereby Congress would be left defenseless.

In one of his greatest acts, Washington defused the crisis with a bit of theatrics. He was given an opportunity to speak and made an appeal directly to his officers that they not undo the victory that they had won. Sensing his audience growing weary and listless, Washington removed from his pocket a letter that had been written to him by a member of Congress. As he struggled to read its contents, Washington next removed a pair of spectacles from his pocket, saying “Gentlemen, you must pardon me. I have grown gray in your service and now find myself going blind.”

His action stunned the assembly. Only a few of his closest associates had ever seen him wearing his glasses. In his vulnerability, Washington showed his greatest courage. Men who moments before had been angry and hostile suddenly burst out in tears. Washington soon left the men to their business. They voted to reject the Newburgh Address to Congress “with disdain,” and instead pledge fealty to that body.

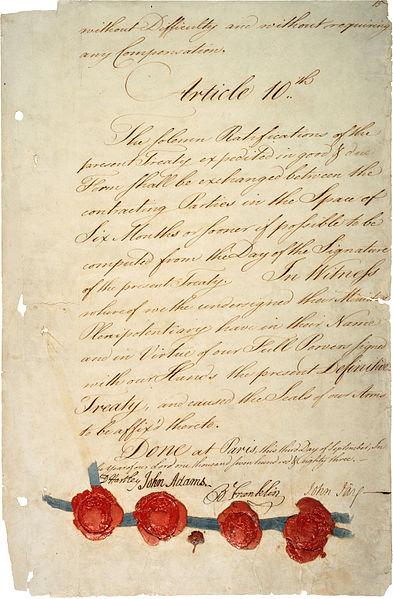

After the Treaty of Paris, 1783, had been signed on September 3 and American independence established, all that was left to do was to disband the army send the men home to now make a new nation. Word reached the American army at the end of October. On November 2, from his headquarters near Princeton, New Jersey, Washington issued his farewell address and orders “to the Armies of the United States of America.”

In his remarks he stressed, “it is earnestly recommended to all the troops that with strong attachments to the Union, they should carry with them into civil Society the most conciliating dispositions; and that they should prove themselves not less virtuous and useful as Citizens, than they have been persevering and victorious as Soldiers… Every one may rest assured that much, very much of the future happiness of the Officers and Men, will depend upon the wise and manly conduct which shall be adopted by these, when they are mingled with the great body of the Community.”

On November 15 his officers submitted their response to Washington’s final orders, “Relieved at length from long suspense, our warmest wish is to return to the bosom of our Country, to resume the character of citizens… and it will be our highest ambition to become useful ones.. We sincerely pray God [that] this happiness may long be yours – and that when you quit the stage of human life, you may receive from the Unerring Judge the rewards of valor exerted to save the oppressed, of patriotism and disinterested virtue.”

Once the British evacuated the City of New York, at the end of November Washington reoccupied the city. On December 4, at an emotional farewell dinner, held at Fraunces Tavern, with his immediate military family, Washington said, “With a heart full of love and gratitude, I now take leave of you,” tears streaming down his face. “I most devoutly wish that your later days may be as prosperous and happy as your former ones have been glorious and honorable.” There was not a dry eye in the room as each man embraced Washington and received a kiss on their cheek from their commander.

Leaving New York, Washington headed to Annapolis to meet with Congress. On December 23, 1783, Washington returned his military commission to Congress. Once more his steely resolve failed to hold up as he began to read his remarks, but when he came to the most important clause in his Farewell Address his composure returned. “Having now finished the work assigned me, I retire from the great theatre of action; and bidding an Affectionate farewell to this August body under whose orders I have so long acted, I here offer my commission, and take my leave of all the employments of public life.”

With the return of his commission to Congress, Washington secured his legacy as the American Cincinnatus, and like the ancient Roman farmer turned victorious general returned to farmer centuries before, citizen George Washington headed home, arriving at his beloved Mount Vernon on Christmas Eve.

Little then did Washington to know what destiny awaited him. In 1787 as the new nation struggled to live Washington came to public service, once more with the best interest of America at heart, when he presided over the Constitutional Convention. Shortly thereafter he was unanimously elected the first President of the United States where he would shepherd the country through the early tumult of the nascent American republic.

It was expected that George Washington would be buried in a special crypt as part of the new United States Capitol, for which Washington had laid the cornerstone, but his wife Martha’s will prevailed and he was buried in a bucolic setting on the grounds of his beloved home and estate, Mount Vernon, Virginia, several miles downstream the Potomac River, from the capital city that bears his name. Upon learning of his death in 1799 his fellow Virginian, friend, revolutionary, and contemporary Henry Lee called him “first in War, first in Peace, and first in the hearts of his countrymen.”