Forts Heiman, Henry, and Donelson

Jim Jobe, for Hallowed Ground

On May 7, 1861, the state of Tennessee decided to withdraw from the Union and join the Confederacy. Southern leaders hoped Kentucky would follow Tennessee’s example, giving the South a formidable northern boundary on the Ohio River. Kentucky’s decision not to follow Tennessee out of the Union forced Southern leaders to defend the Tennessee border. Unfortunately for the Confederacy, the Mississippi, Tennessee, and Cumberland Rivers crossed this state border and each river provided opportunity for Union invasion.

For the Union to prevail, armies had to be sent into Confederate territory. The Union Army faced the daunting task of occupying and controlling this vast area. In order to accomplish this task, large armies had to be trained, supplied, and moved into the South. Supply lines had to be developed and maintained. The ability to keep this army supplied and reinforced was so critical that victory could not be achieved without the use of rivers and railroads. The Southern strategy of defending its borders to secure their new country required controlling these major transportation routes. In short, controlling the rivers and railroads would be vital for the success of the Union and the Confederacy.

Governor Isham Harris of Tennessee decided to begin work on the defense of his state. He dispatched engineers to select sites for forts on the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers. The engineers were told to select sites north of railroad crossings and south of the Tennessee and Kentucky State line. Fort Donelson was built on the Cumberland River on a high bluff near Dover, Tennessee. A site for the Tennessee River fort was not as easy to locate. After receiving several opinions, Governor Harris decided to build Fort Henry on low ground frequently flooded by the Tennessee River. The poor location on which Fort Henry was built forced Confederate leaders to also occupy and fortify the high ground across the Tennessee River from Fort Henry. This work was named Fort Heiman.

On November 7, 1861, Union General Ulysses S. Grant led a force against the Confederate camp at Belmont, Missouri. The results were inconclusive but it gave Grant a good close view of the Confederate work at Columbus, Kentucky. Grant was also receiving scouting reports that Fort Henry was in a weak position. He began seeking permission from his superior, General Henry Halleck, to attack Fort Henry. General Grant was initially rebuffed, but when the request was reiterated with Flag Officer Andrew H. Foote’s recommendation, Halleck agreed. Grant began ferrying his troops to a spot just north of Fort Henry. By February 6, 1862, General Grant had his force of 15,000 and Foote’s gunboats in place and ready to attack.

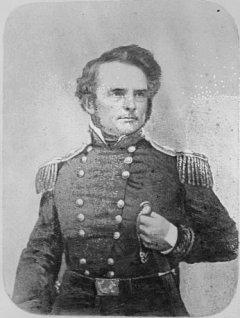

The news of the Union build-up close to Fort Henry was reported to Confederate General Lloyd Tilghman, commander of Forts Heiman, Henry, and Donelson. General Tilghman found himself in an ominous situation. Forts Henry and Heiman were garrisoned with only 2,500 men. Fort Henry was already partially flooded, the river was rising, and a vastly superior force, including ironclad gunboats, threatened him. By the time Grant made his move against Forts Heiman and Henry, Tilghman had the Fort Heiman garrison ferried to Fort Henry and had most of both garrisons stationed outside the fort in preparation to move to Fort Donelson. Tilghman retained just enough men at Fort Henry to operate the heavy guns.

Grant divided his army and sent General C.F. Smith’s Division on the west bank to attack Fort Heiman while General John McClernand’s Division moved along the east bank to Fort Henry. The fleet of gunboats, consisting of ironclads Cincinnati, Essex, St. Louis, and Carondelet and timberclads Conestoga, Lexington, and Tyler, made up the third prong of the Union attack. Foote took advantage of the elevated water level, and used a chute around the west side of Panther Island. This allowed the gunboats to get closer to the fort without being fired upon by the Confederate gunners. The gunboats emerged from the chute and lined up in battle formation, keeping their bows turned toward the fort, and they opened a tremendous fire. Fort Henry answered with its eleven heavy guns, but the bow guns of the gunboats had more firepower than the fort could match. This, along with the poor position of Fort Henry, gave Foote’s gunboats the advantage. Foote used that advantage and pressed in close to the fort, silencing seven of the eleven heavy guns. One of the heavy guns inside Fort Henry exploded during the battle, killing most of the crew.

The gunboats did not come away unscathed. The Essex took a round in her boiler, sending scalding steam through the boat. Many sailors jumped overboard to avoid being scalded to death. Many more did not have the chance to jump and were found dead at their posts. The damage sustained by the Cincinnati was extensive enough that repairs could not be made in time to participate in the Fort Donelson battle.

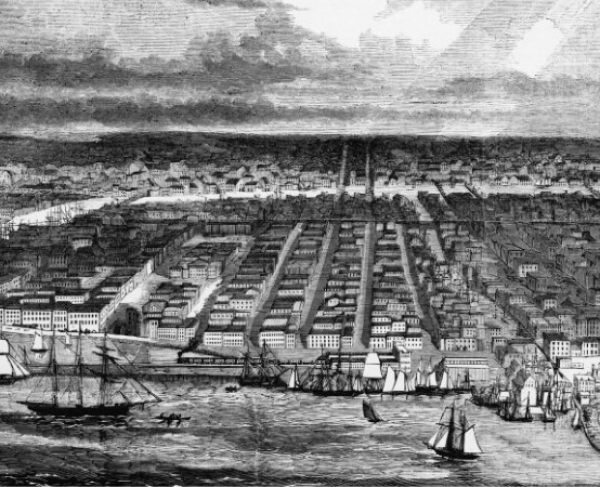

General Tilghman decided further resistance was futile and ordered a white flag to be raised. The Union Navy had captured the fort while the Army, delayed by swollen streams and muddy roads, was still trying to make its way to the battlefield. The Tennessee River was now open for the Union. Timberclad gunboats steamed all the way to Alabama, damaging bridges and capturing boats, including a partially constructed ironclad. The ironclad gunboats returned to Cairo, Illinois with instructions to hasten repairs before steaming up the Cumberland River to Fort Donelson.

The Confederate command was in dismay. Nobody expressed confidence in any earthen fort holding against the ironclad boats. “Fall back” was the order. The only person to see Grant’s position on the Tennessee River as weak was his commander, Henry Halleck, who began sending him reinforcements. Confederate General Albert Sidney Johnston, believing Fort Donelson would fall to the gunboats as Fort Henry had done, felt that his army’s position at Bowling Green, Kentucky was threatened. Johnston’s forces faced Union General Don C. Buell’s army north of Bowling Green. If Grant brought his army up the Cumberland River to Nashville, Tennessee, General Johnston would find himself trapped between the two Union armies. Johnston decided to reinforce Fort Donelson to delay Grant and cover his own retreat from Bowling Green to Nashville. He sent about 12,000 men, including Generals John B. Floyd, Gideon Pillow, Simon B. Buckner, and Bushrod Johnson, from southern Kentucky and northern Tennessee. These men pressed forward to strengthen Fort Donelson. The Confederates mounted heavy guns in the water batteries, built and extended earthworks, and cut trees to open fields of fire. But they made no effort to hamper, harass, or delay General Grant as he prepared to move against Fort Donelson.

Union cavalry was able to scout the area and obtain good information about road conditions between the two forts. Grant accompanied one of the patrols and rode to within sight of Fort Donelson, thus obtaining valuable information about the lay of the land, before he decided to leave Fort Henry and attack Fort Donelson. The weather had been warm and spring-like.

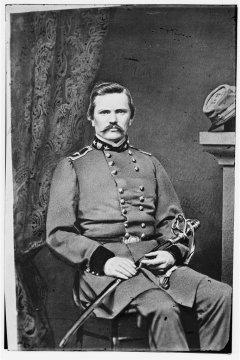

On February 11, 1862, Grant’s Union army began its march across the twelve miles to Fort Donelson. Grant was also able to send several regiments around by water. He left one brigade, under the command of General Lew Wallace, to hold Fort Henry. McClernand’s Division arrived at Fort Donelson on February 12 and began surrounding the fort. McClernand moved to the east side of the work while Smith’s Division moved to occupy heights along the west side of Fort Donelson later that same day.

On February 13, the Union continued to position and surround the fort. Both division commanders ordered attacks against the Confederate works without success. By this time, Fort Donelson had been reinforced, bringing its garrison to 15,000 to 17,000. Grant was facing an army roughly the same size or perhaps slightly larger than his own. He sent word for Wallace at Fort Henry to bring his brigade forward. That night the wind shifted and the temperature began to drop. A heavy rain that soaked both armies was followed by a snowstorm that lasted all night. Morning dawned with two inches of snow on the ground and temperatures well below freezing.

The Union Navy was also moving. The Carondelet, the first ironclad gunboat to arrive, tested Fort Donelson at long range. On February 13, the Carondelet scored a hit and dismounted one of the heavy guns inside the water battery.

The Union regiments Grant had sent around by water arrived below Fort Donelson. Grant organized these regiments into another division under General Lew Wallace and placed them in the center of the Union lines. By February 14, Grant’s army had grown to 27,000 men and Fort Donelson was surrounded on the land side. Only the Cumberland River toward Nashville was still open for possible Confederate reinforcements.

Grant was hoping his ironclad gunboats would be as successful at Fort Donelson as they had been at Fort Henry. If the gunboats could silence the fort or get past the fort, Fort Donelson would be surrounded without hope of reinforcement or supplies. Time would then force the Confederates to surrender. On Valentine’s Day, the ironclad fleet of St. Louis, Pittsburgh, Louisville, and Carondelet with the timberclads Conestoga and Tyler, made ready to attack. The four ironclads moved into battle formation, four abreast with their bows pointed toward the fort to open fire. They would have to run a gauntlet through a narrow channel of one-and-one-half miles to reach Fort Donelson. The Confederates were ready, and opened fire with their two largest cannons, a ten-inch Columbiad and a six-and-one-half-inch rifle. The gunboats continued to close the distance to the fort. Once the boats had pressed to eight hundred yards, they came under the fire of seven thirty-two pounders. Fort Donelson was built on much higher ground than Fort Henry. The closer the gunboats came to the fort, the more the Union gunners had to elevate their gun muzzles while, at the same time, the easier it was for the defending Confederates to shoot down on them. The result was the nearer the boats got, the more the Union aim deteriorated while the Confederate aim improved. The gunboats continued to press to within four hundred yards of the fort. A solid shot entered the pilothouse of the flagship St. Louis killing the pilot, damaging the wheel, and wounding Flag Officer Foote. The St. Louis became difficult to steer and began to fall back. The Louisville began to fall back after receiving several shots and having its tiller cables cut. The Pittsburgh had received two rounds in the bow between wind and water, meaning the rounds went under the armor and penetrated the wooden hull. The Pittsburgh was taking on more water than the pumps could pump out. The bow guns were run back and repair parties went to work to slow the water leaking into the vessel. These measures saved the gunboat from sinking, but it too had to retire. This left the Carondelet alone to face the heavy batteries. Every cannon trained on the single boat and forced it to fall back with the remainder of the fleet. The gunboat attack had failed. The hills and hollows surrounding Fort Donelson echoed with Confederate shouts of victory.

This news sent shock waves through the Union Army. General Grant began to contemplate siege, but Confederate Generals Floyd, Pillow, and Buckner would not give Grant the chance. Once they got through celebrating the victory against the gunboats, they began to take a long, hard look at their situation. The Confederate forces were spread out evenly around the two-and-one-half miles of outer earthworks. Simon Buckner was in command of the Confederate right while Bushrod Johnson was in command of the Confederate left. Gideon Pillow had been in overall command of the fort until the arrival of John B. Floyd on February 13. The Confederate generals realized that, while they had defeated the gunboats, they were still surrounded by a superior force whose numbers had been growing while their numbers had not. Johnston had sent them to Fort Donelson to delay General Grant and to cover Johnston’s withdrawal from Bowling Green. They had additional instructions to then remove the army from the fort and join General Johnston in Nashville. The Confederate generals agreed the time had come to act. They decided on a plan to break through the Union lines and take their army out to Nashville using two roads on the Confederate left wing. The plan called for Pillow to take command of Johnson’s Division and to mass them on the extreme left of the Confederate lines. Confederate Colonel Adolphus Heiman’s Brigade would hold its position in the Confederate center. Buckner’s Division would move into the gap between Heiman’s Brigade and Pillow’s Division. This would place most of the Confederate army on the left wing and almost nobody on the right wing.

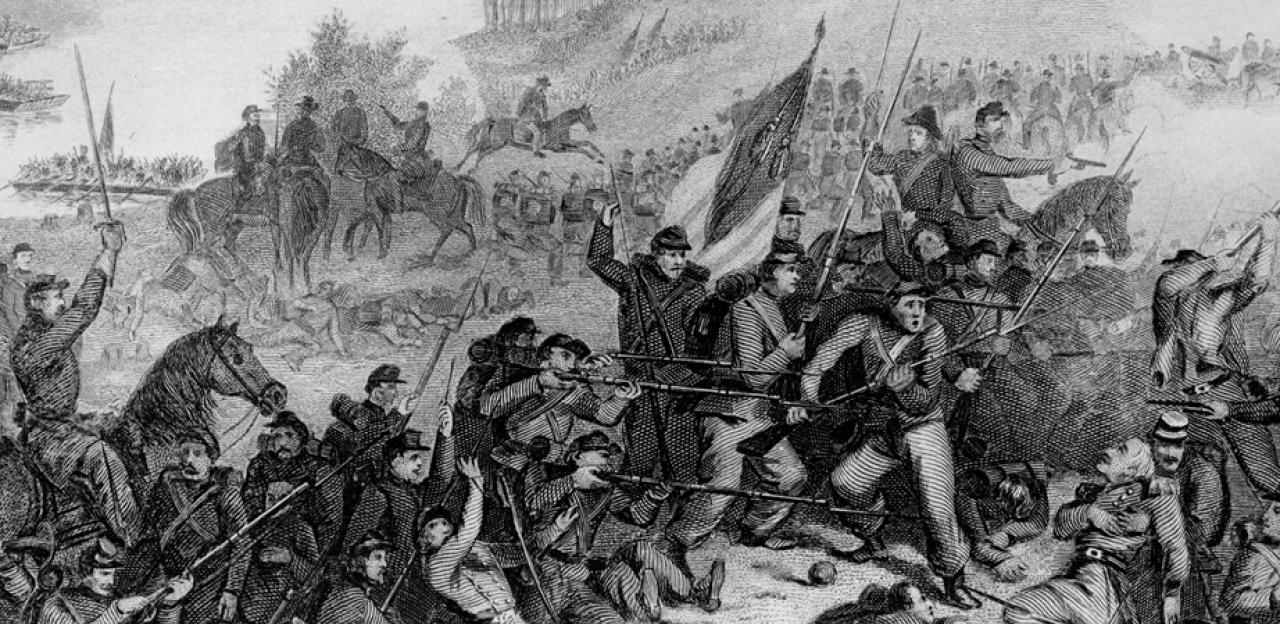

The plan called for Pillow’s Division to launch the attack against the Union right. Once the Union right was turned and being forced back around the earthworks, Buckner’s Division would join the attack. Once the roads were open, the retreat to Nashville could take place. At daybreak on February 15, Pillow’s Division hit the Union right, under General John McClernand, hard. This massed and determined attack began to turn the Union right and forced them back along the roads used to surround Fort Donelson. McClernand realized he was in trouble and sent word to the other division commanders and to Grant requesting help. Grant had not anticipated this type of action from the Confederates. He had left his headquarters before daylight and traveled several miles downstream to inspect the gunboats. The only instructions left to his division commanders was to hold their positions and not to bring on a general engagement. Instead, the Confederate generals had brought the engagement to the Union Army. During Grant’s absence, no one was there to make a decision. McClernand’s rider was told he would find General Grant somewhere downstream. This confusion helped the Confederates, and the Union right continued to give way. Lew Wallace, division commander for the Union center, eventually decided that, if he were going to hold his position, he would have to help McClernand hold the right wing. C.F. Smith, division commander for the Union left, also sent one brigade to help McClernand. By mid-afternoon, McClernand’s Division had been pushed off the battlefield and was trying to reform while Wallace’s Division and the brigade from Smith’s Division had crossed Indian Creek and moved into position to block the Confederate attack. This Union position was well beyond the River and Forge Roads, which meant that those roads were open to the Confederates as escape routes to Nashville.

The Confederate attack seemed to stall and there was a lull on the battlefield. Buckner ordered additional infantry regiments and artillery forward to strengthen his position. He intended to press the attack or hold his position so that the rest of the Confederate Army could escape while his division served as a rear guard. Pillow sent a telegram to Johnston, in Nashville, announcing, “…The day is ours,” and sent orders directing Buckner and all Confederate forces to withdraw inside the earthworks. Buckner questioned the order. He did not see the reason to simply give up all the area they had fought for and won that day. Pillow reiterated his original order and Buckner reluctantly began to comply. General Floyd arrived and asked why Buckner was moving back inside the earthworks. Buckner expressed his disagreement with Pillow’s order and Floyd went to confer with Pillow. Ultimately, the Confederate command decided to pull back inside the earthworks.

While the Confederate generals were arguing and debating about what actions they should be taking, Grant arrived on the battlefield. He found confusion among some of the Union forces; men wandering around with empty cartridge boxes while wagons of ammunition stood nearby. Captured Confederate soldiers with knapsacks and bedrolls had caused fear that the Confederates were prepared to fight the Union army back to Fort Henry. Grant realized that the Confederates in Fort Donelson were trying to escape and he began issuing orders to get these regiments back into line and properly equipped with ammunition. He ordered Wallace and McClernand to retake the area lost during the morning attack. He also believed that, for the Confederates to have hit him so hard in one place, they must have weakened their line somewhere else. He rode off to order General Smith to attack the Confederate right wing. As he was riding along, he yelled to the men to rally, not to let the enemy escape, and the men responded well.

Upon receiving orders to attack the works in front of his division, General Smith moved his forces down the ridge and formed for battle at the bottom of the Confederate-occupied hill. He gave his men an inspiring talk, saying that they had volunteered to die and that now was their chance. He placed his hat on his saber and, while mounted on a white horse, led the advance up the hill. There were very few Confederate forces at the top of the hill to greet them and Smith’s Division easily captured the right wing of the earthworks. The Confederates fell back to the next ridge to regroup. Buckner’s Division arrived in time to hold this ridge against the attacking Union soldiers. The Union forces fell back and the lateness of the hour prevented any further attacks. The long, bloody day closed with the Confederates back inside the works on their left and with the works on their right firmly held by the Union army. Through indecision and debate the Confederate generals had missed their opportunity to evacuate, while the decisiveness and leadership of General Grant had preserved the Union position.

During the night of February 15, the Confederate commanders met to decide their next move. There was no improvement in cooperation between these generals. Pillow wanted to leave the sick and wounded behind and force their way out. Buckner believed they had lost the element of surprise and had no options left. The generals received varying reports as to the position of the Union army and how much of the area opened by the Confederates had been reoccupied. They did receive one accurate report that River Road was open, but the mud was knee-deep and the water was up to the saddle skirts. The surgeons believed that men forced to wade the water in the cold February weather would die of exposure. As the long night wore on, surrender seemed to be the best option. John B. Floyd declared that, due to personal reasons, he would not be part of the surrender. He asked General Buckner if Buckner would agree to take command so that he could draw out his personal brigade before the capitulation. Buckner replied that Floyd and his brigade could leave, as long as they did so before General Grant had time to reply to his communication. And so, General Floyd turned over his command (which General Pillow passed) leaving Buckner to accept the command and begin communication with Grant about terms for surrender.

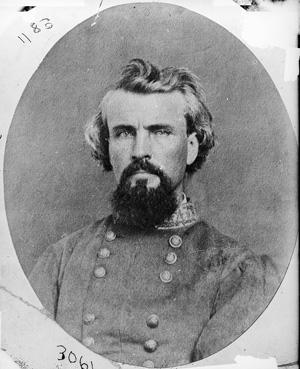

Colonel Nathan Bedford Forrest, in command of Confederate cavalry, was aware that the generals were contemplating surrender. Forrest had been providing scouting reports to the generals, but had had little, if any, influence on their decisions. When it was confirmed that the Confederate command planned to surrender, Forrest vowed to take the cavalry out even if he saved only one man. Generals Floyd and Pillow were also making plans to leave when an unexpected boat appeared at the landing with 400 reinforcements. Floyd had the boat unloaded and placed a guard around it. He ordered his personal brigade onboard and ferried most of them across the Cumberland River where they marched to Clarksville, Tennessee accompanied by General Pillow. Floyd and the last load of soldiers left Clarksville by water on their way to Nashville.

As the sun rose in the eastern sky on February 16, 1862, both Union and Confederate soldiers were surprised to see white flags flying over the Confederate works. Buckner sent a message to Grant proposing an armistice while terms of surrender could be discussed. U.S. Grant sent back the ultimatum that would make him famous: “No terms except an unconditional and immediate surrender can be accepted. I propose to move immediately upon your works.” General Buckner accepted what he named “ungenerous and unchivalrous terms.” Now the Cumberland River was also open to the Union army. The battle count for both sides was 4,332 casualties.

Grant and Buckner met at the Dover Hotel, site of Buckner’s headquarters, to formalize the surrender. During the next few days, approximately 13,500 Confederate prisoners began their trips to prison camp and an uncertain future. Northern newspapers reporting the events dubbed the Union commander, “Unconditional Surrender” Grant. All of the Union generals were promoted to Major Generals and Washington began to take notice of Grant’s abilities. The Confederacy abandoned southern Kentucky and most of middle and west Tennessee. The Union army had control of the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers and occupied Nashville. This provided the Union a base with a river and rail network that allowed a huge influx of the men and materials necessary to conquer the South.

The war would continue three more years. Larger battles would be fought and many more men would lose their lives before the war ended. When Confederate General Albert Sidney Johnston was told that Fort Donelson had surrendered, he deemed the loss “disastrous and almost without remedy.” The next three years would prove him right.

Today, Fort Donelson National Battlefield, a unit of the National Park Service, owns approximately twenty percent of the 1862 battlefield. The main work at Fort Henry is under the Kentucky Lake, but much of the outer works remain and is part of Land Between the Lakes National Recreation Area, operated by the National Forest Service. The high ground on which Fort Heiman was built saved it from a watery grave, but it is privately owned and is for sale as lake front property.

Related Battles

2,691

13,846