Fort Fisher

The Second Battle of Fort Fisher

After the Union army and navy sealed off Mobile Bay in August of 1864, only one major port remained opened for the Confederacy: Wilmington, North Carolina. Access to the port of Wilmington was via the Cape Fear River, which ran in a north-south direction on the city’s west side before emptying into the Atlantic Ocean some 20 miles south of the city. A peninsula of land on the east side of the river sheltered the river and ships from the Federal North Atlantic Blockading Squadron. Bolstering the area’s natural defense were a series of Confederate fortifications, with the primary fortification being Fort Fisher, an upside-down L-shaped fort that was dubbed (as many others were ) the “Gibraltar of the Confederacy.”

The southern defenders of Wilmington and Fort Fisher were overseen by a troupe of Confederate castaways: Braxton Bragg, Alfred Colquitt, William Lamb, William H.C. Whiting, and Robert Hoke. Of the quintet, Hoke was the only capable commander in the sector. Luckily for the Confederates, the Union did not send their best and brightest to Wilmington, either—at least initially. Major General Benjamin F. Butler, a political general through and through, performed poorly in the Eastern and Western Theaters of the war. But his political connections made him such a problem for the Union high command that he had to receive prominent positions.

The first Battle of Fort Fisher (Dec. 23-27, 1864) was more of a Gallipoli than a Normandy. An ill-timed naval bombardment tipped off the Confederate defenders. A Federal ship packed with tons of explosives failed to make contact with Fort Fisher’s defenses and harmlessly blew up at sea. And when the Federal infantry did land, they were quickly evacuated. Butler was sacked.

In January of 1865, a second attempt was made to secure Fort Fisher, and this time the Federals placed two capable men in command: Maj. Gen. Alfred Terry and Rear Adm. David D. Porter. Terry collected nearly 10,000 Union army soldiers while Porter arrayed 58 ships offshore in roughly three lines of battle. Porter would pummel the Confederate defenses and land the army on shore. Once ashore, a division of United States Colored Troops (USCT) would advance north up the peninsula and assume a blocking position—their primary mission was to hold back any Confederate reinforcements from Hoke’s division. A second force of Union infantry would establish a line facing south and attack the landward wall of Fort Fisher. A third force of sailors and United States Marines, some 2,000 in all, would land and attack the seaward wall of the fort. In terms of ships and men, the assault on Fort Fisher was the largest and most complex amphibious operation in U.S. history until World War II.

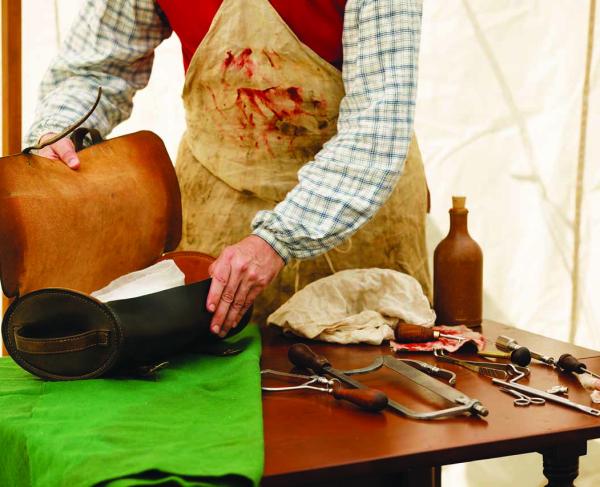

On January 13, Terry’s soldiers established a beachhead north of Fort Fisher. After a reconnaissance of the Fort on January 14, the Federals concluded to attack the next day. On January 15, the Union Navy pounded the Confederate defenses south of Wilmington. Three successive waves of sailors and marines were to attack the eastern seawall. Like something from an Errol Flynn movie, the 2,000 sea dogs and leathernecks crashed into the defenses with pistols and cutlasses in hand in one great wave of humanity. The 1,900 Confederate defenders focused on this initial assault as the division of Brig. Gen. Adelbert Ames smashed into the land wall. The battle was intense and furious. Although greatly outnumbered, the Rebel soldiers clung tenaciously to their defenses. Seven of Ames’s thirteen regimental commanders were killed or wounded, and all three of his brigade commanders fell as casualties, too.

Whiting pleaded with Bragg for reinforcements. Bragg refused, not taking the situation at all seriously. After repeated pleas from Whiting, Bragg sent Alfred Colquitt to the fort with orders to relive Whiting. By the time Colquitt arrived, Confederates were evacuating the fort and Whiting and Lamb lay wounded. After hours of battle, the Confederate’s surrendered the fort. Rebel defenses around Wilmington crumbled, and the city fell to Union soldiers roughly one month later. The last Confederate port was locked shut, and the flow of outside supplies ceased to reach the languishing Confederate field armies.