Forgotten Flanks of Gettysburg

The Civil War Trust is currently working to preserve 112 acres at the Gettysburg battlefield—the "forgotten flanks" of the Union and Confederate armies. Here, Garry Adelman discusses the importance of these sites and dynamic nature of the armies' movements during the battle.

Understanding a battle is easier if you know where the armies were positioned when they fought. Just determine where the right and left flanks of the opposing armies were located and you are left with four points. Connect the dots and you have a battle map! This sounds fun and simple but doesn’t really work—battles are dynamic events; opposing forces move around throughout an engagement.

At the Battle of Gettysburg, as the Army of the Potomac and the Army of Northern Virginia struggled for three days, July 1-3, 1863, there were scores, if not hundreds, of places where the extreme right and left flanks of the armies stood. The armies met in small pieces and then grew in size. The scene of the fighting moved from north and west of town then south and each time a regiment on the end of the line was moved or added, the site of the extreme flank changed. Most of these flank positions only served in that capacity for mere minutes or hours--none for a full day. There are infantry and artillery flank positions but often the more mobile cavalry operated far from the main body and was disconnected from the rest of the line of battle. Which positions count as extreme flanks? There is no clear choice.

While many temporary army flank positions at Gettysburg are well known to history—McPherson’s Woods, Barlow’s Knoll, Culp’s Hill, Seminary Ridge, Little Round Top—others have been forgotten to history and have seen little preservation since the battle.

As the Second Day's fight swirled on the south end of the battlefield, the Union army’s flanked changed numerous times to address the advance of Confederate General John Bell Hood's division. From Devil's Den to Little Round Top to Big Round Top, the Union left flank moved at least eight times. In the early morning hours of July 3, the Union Sixth Corps extended the left flank to the east of the Round Tops, first to the Taneytown Road and then to its east. Men from the 5th Wisconsin, General David A. Russell’s Brigade, were positioned along a double-fenced farm lane, on the extreme left flank of the entire army. A battery of New York artillery unlimbered to their right front and the Union left flank was relatively secure. When Pickett's Charge commenced around 3:00pm, this brigade, along with roughly 30% of the Union army, was ordered to the center to help repel Pickett’s Charge. Thus, the Union left flank changed positions again.

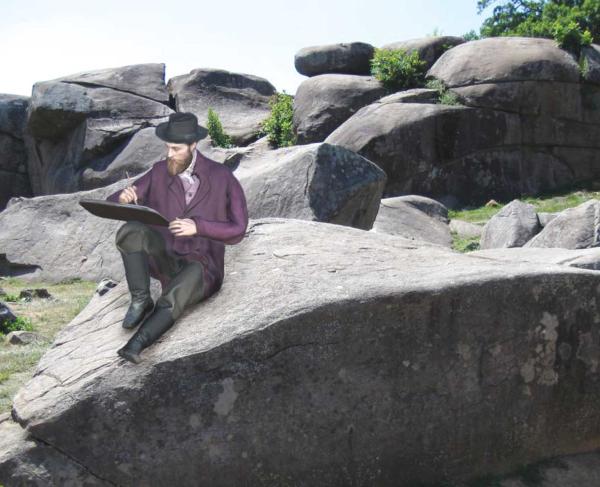

On the opposite side of the line, the opposing forces also moved numerous times as they jockeyed for advantageous military positions. The Confederates moved a strong skirmishing force of North Carolinians and Virginians to the east side of Rock Creek on Wolf Hill to engage and work their way around what was then the extreme Union right flank near Spangler's Spring. These men belonged to General George "Maryland" Steuart's Brigade and the famous Stonewall Brigade—a skirmish line to be reckoned with! The Virginians and North Carolinians took position and sniped from rocks and trees on Zephaniah Taney's farm.

Soon, two Union regiments, then four, belonging to General Thomas Neill's Sixth Corps brigade also moved to the east side of the creek. Neill took position along a stone wall on a rise as the 2nd Virginia changed positions to fight with Neill. This put the 2nd directly on the farm of John Taney and shooting into Union forces at Jeremiah Taney's house. For the soldiers positioned on the Confederate left flank and the Union right flank, July 3rd was not about the famous Pickett’s Charge—it was about the skirmishing in the woods and fields on Wolf Hill that killed or wounded more than twenty of their comrades. This was their Battle of Gettysburg.

Men of both armies on Wolf Hill could hear (and probably feel) the immense bombardment that preceded Pickett’s Charge from roughly 1:00p.m. to 2:30p.m. So could the soldiers in the Georgia, Pennsylvania, South Carolina and U.S., units on the opposite flank, which had by then moved out to and west of the Emmitsburg Road. General Wesley Merritt’s Brigade of cavalry was pressing the extreme Confederate right flank consisting of men from the 1st South Carolina Cavalry and later by a growing number of Georgia regiments from Gen. George "Tige" Anderson’s Brigade, supported by a few cannons. As Pickett's Charge played out, Union and Confederate forces were fighting in a much smaller engagement west of the Emmitsburg Road. Merritt's advances gained nothing and the army flanks were in motion again. Even as this fighting raged, one of Merritt’s regiments had skirted eight miles to the west to engage Confederates at the town of Fairfield. Soon, the flanks of both armies were back in Virginia.

The study of the Battle of Gettysburg must be as dynamic and broad as were the movements and actions of the opposing forces. Learning about the 50 or 150 places where the men occupied the extreme flanks stood, shot, slept and struggled in the Civil War’s greatest battle, is paramount.

Related Battles

23,049

28,063