With the debut of so many technological innovations, many historians view the Civil War as the first “modern war.” Although the phrase typically conjures images of ironclad warships and trench warfare, the war’s first major battle saw its own fair share of revolutionary ideas put into practice on the battlefield.

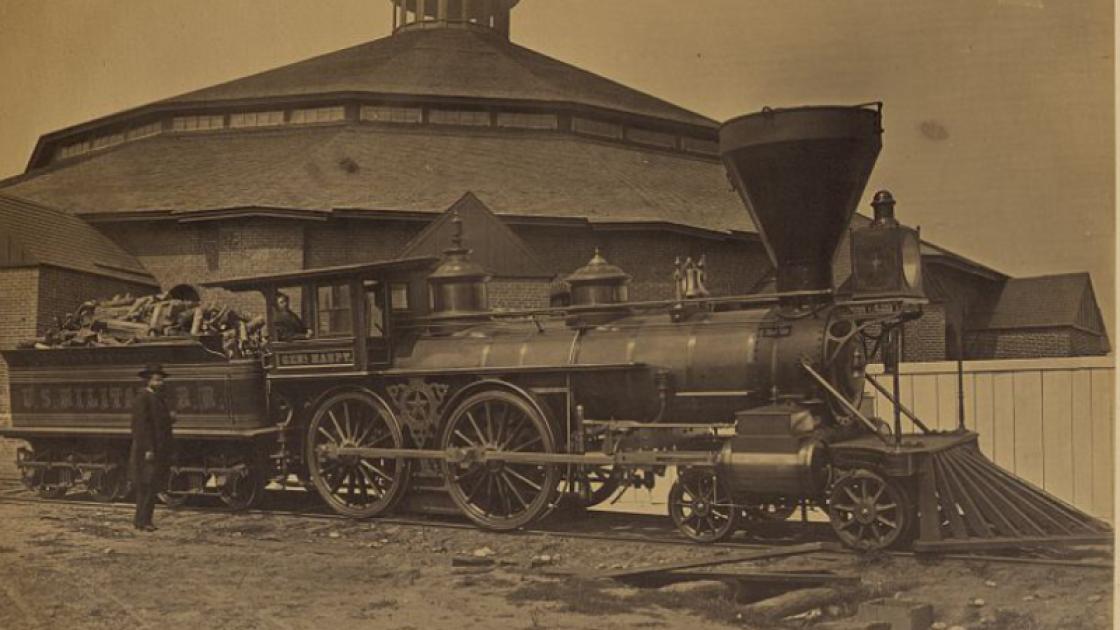

Railroads

Although about two-thirds of available railroad track lay in the North, Southern officers were first to seize on the idea of using trains for rapid troop transport. Realizing their main body of troops was outnumbered, Confederate forces in the Shenandoah Valley marched from Winchester to Delaplane and boarded train cars of the Manassas Gap Railroad to travel east to Manassas Junction. Arriving in time to reinforce key positions, they played a major role in turning the tide of battle for the Confederacy. Both sides quickly saw the potential for the railroads to play a major part in military campaigns, and soon major rail centers, like Chattanooga and Atlanta, found themselves at the center of a maelstrom of conflict.

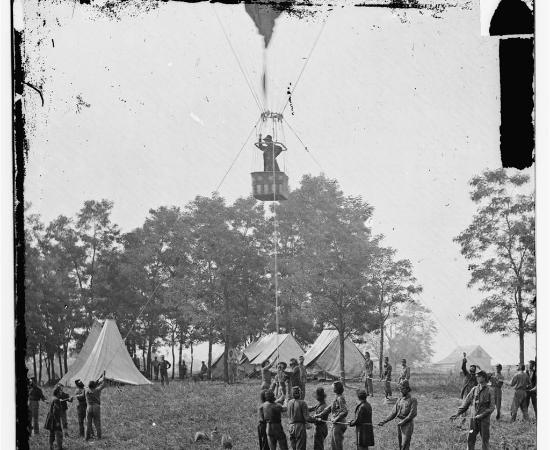

Balloon Reconnaissance

Professor Thaddeus Lowe was in the right place at the right time. He had arrived in Washington, D.C., in June of 1861 and demonstrated for President Lincoln how his hydrogen-filled balloon Enterprise could rise to a height of 500 feet and send telegraphic messages to the War Department via its long tether cords. Impressed, Lincoln requested that Lowe remain in the city while the government deliberated on the possible military use of balloons.

On July 24, after receiving contradictory reports on the strength and location of Confederate forces near Manassas, Brig. Gen. Irvin McDowell requested that Professor Lowe go up to ascertain the situation. Although successful in transmitting key information, Lowe’s balloon landed behind enemy lines. Initially located by soldiers from the 31st New York, Lowe was unable to move due to an injury sustained to his ankle in the descent. Eventually rescued along with all his equipment by his wife, Lowe went on to be the commander of the civilian Balloon Corps, a division of the Bureau of Topographical Engineers.

Signal Corps

On May 1, 1861, Edward Porter Alexander resigned his commission in the U.S. Army to join the Confederate Army as captain of engineers. Earlier in his military career, Alexander had served as an assistant to Maj. Albert Meyer, the first U.S. signal officer and the inventor of a system that utilized flags and binary code system to transmit messages across a distance of up to 15 miles. He immediately began training a Confederate Signal Corps using the method and, on June 3, he was ordered to report to Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard at Manassas Junction. During the battle, from his position atop “Signal Hill,” Alexander observed a large body of Union troops converging on the Confederate left flank almost eight miles away. In the first use of “wig-wag” signaling in combat, Alexander sent the message, “Look out for your left, your position is turned.” Receiving the message, Col. Nathan “Shanks” Evans repositioned his troops to face the new threat, a key moment contributing to the ultimate Confederate victory.

Related Battles

2,896

1,982