First Deep Bottom

The Battle of First Deep Bottom

Darbytown, Strawberry Plains, New Market Road, Gravel Hill,

With the investment of Petersburg stretching into its second month, in July of 1864 Union general Ulysses S. Grant was searching for ways to thin and break the Confederate lines around the vital city. He opted to revisit an operation he had attempted against Vicksburg the previous summer—mining, igniting, and destroying a section of the Petersburg fortifications in preparation for an infantry assault.

The bomb was set to go off on July 30. To further weaken the Confederate defenses, Grant ordered a series of diversionary maneuvers to take place in the days before the main attack. One of these expeditions resulted in the Battle of First Deep Bottom.

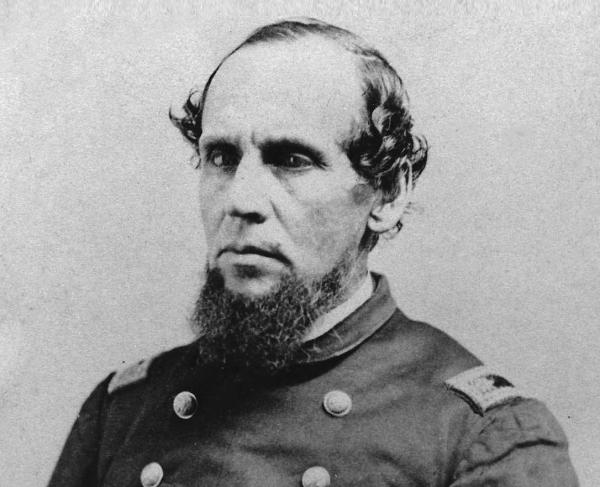

Early on July 27, Winfield Scott Hancock’s II Corps, along with two divisions of Phil Sheridan’s cavalry, left the lines around Petersburg and moved north, crossing the James River near a sharp bend known locally as Deep Bottom. Their objective was to threaten Richmond and compel Robert E. Lee to dispatch a substantial portion of the Petersburg defenders in order to check the advance.

Lee had no choice but to act to defend the capital city, sending six brigades north to fortify the New Market Heights. From this eminence the Confederates covered the Union army’s likely approaches to Richmond.

In order to threaten Richmond, Grant had outlined two possible scenarios for operational success. The first scenario was for Hancock’s infantry to pin down the Confederate defenders so decisively that Sheridan’s cavalry could wheel around the battle and ransack the city itself. The second scenario was for Hancock’s infantry to pin down enough of the Confederate defenders to allow Sheridan to ride west of Richmond and strike the railroad supply lines from the Shenandoah Valley.

The July 27 advance began well for Hancock’s expeditionary force. His lead elements managed to scatter a Confederate outpost blocking his route north and even captured four cannons. Hancock exploited this advantage, moving the rest of his men across the James and deploying them for an advance west to Richmond, which was approximately nine miles away.

The Confederates had also reshuffled their line to follow a watercourse known as Bailey’s Creek, which ran north-south between the contending forces. Hancock reacted to this by dispatching Sheridan’s cavalry to Gravel Hill, a position that could be used as a stepping stone around the northern extremity of the creek.

The 10th and 50th Georgia regiments attacked the Union cavalry on Gravel Hill and drove them back after a sharp firefight. Repeating carbines, which by mid-1864 were in the hands of many Northern cavalrymen, took a heavy toll on the Georgians. The struggle on Gravel Hill was the last major action of the day, as Hancock chose to conduct further reconnaissance before sending his infantry across Bailey’s Creek.

On July 28, both sides received reinforcements from the Petersburg sector. Having initiated the battle with an eye towards thinning the Petersburg defenses, Grant was no doubt pleased to hear that more Confederates, two more divisions, had arrived on the Deep Bottom battlefield.

Hancock received one brigade from Petersburg, which he used to replace John Gibbon’s elite division along Bailey’s Creek. Gibbon’s men had not yet redeployed when Phil Sheridan ordered his horsemen forward to attack Gravel Hill once again.

The Union cavalry ran headlong into three Confederate brigades that were in the middle of launching an assault of their own. The Confederates gained the initial advantage, but were ultimately driven back by a determined line of dismounted cavalry firing their repeaters from the crest of a gentle slope. The Union men remounted and pursued, capturing nearly 200 prisoners and ending major fighting on the 28th.

Hancock coordinated a withdrawal back across the James late on July 29. While the fighting at Deep Bottom had mostly gone to the Federal advantage, further operations against the Confederate defenses north of the James would require more blood and iron than Grant saw fit to divert at that time. The Battle of First Deep Bottom had succeeded in its primary objective—that of drawing Confederates away from the Petersburg defenses before the bomb was triggered. The battle was a prelude to the Battle of the Crater, which took place the next day.