Escaping the Black Hole

The following is the transcpript of a talk given by the Civil War Trust's Garry Adelman at the March 2013 Future of Civil War History Conference.

The Battle of Gettysburg is the largest and most-studied battle of the Civil War, and of all of the contested areas none has emerged as more popular than the hill now known as Little Round Top--the left flank of the Union Army for about 90 minutes on July 2, 1863. Cleared of much of its timber a few years before the battle, the hill offered excellent fields of fire and thus became a strategically important point on the south end of the battlefield. After savage fighting on July 2, the Yankees retained possession of Little Round Top.

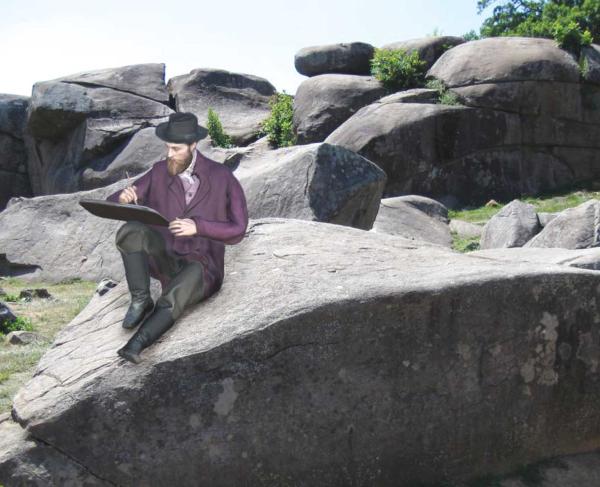

In the days, years, and decades after the fighting, soldiers, civilians, journalists, and historians wrote about what happened there. They argued over the name of the place—Granite Spur, Weed’s Hill, Adam Linn’s Hill, Round Top, Little Round Top. Rock carvings, markers, tablets, monuments and, later, wayside exhibits increasingly dotted the crest and slopes, conspiring to provide a glimpse into the fateful hours on July 2, 1863.

Within days of the battle, writers began to speculate about the importance of Little Round Top. Most were reserved, at first—Little Round Top was but one of many aspects of the battle and few writers even lent it particular significance. As the battle receded decades into the past, accounts and narratives increasingly described a Union disaster if Little Round Top was lost. Veterans of low rank and high argued with each other about aspects of the engagement—who did what, who gets credit, which monuments should be placed where—but none argued against Little Round Top’s growing importance. The legend was on an inexorable roll.

Historians followed the lead of the soldiers and generally discussed, with considerable certainty, the specific events which would have occurred with Little Round Top in Confederate hands. Their theories run the gamut, from turmoil on the Union left flank to Confederate victory in the Civil War. The parallel trajectory that boosted Little Round Top’s importance and popularity, culminating with the Michael Shaara’s The Killer Angels, Ken Burns’ The Civil War, and Ted Turner’s Gettysburg, ultimately portrayed the small hill as the most important, dramatic and pivotal feature at Gettysburg. It stands to reason, then, that the commanders who fought there were the battle’s most significant figures. The majority of books and touring products were created alongside the exponential rise in Little Round Top’s fame but one which grew ever denser and more singular in narrative. This has created for most visitors and enthusiasts a particularly strong interpretive black hole from which reasonable accounts or theories are powerless to emerge. Historians, and therefore those they aim to educate, are only exempt from the gravitational pull if they choose to be, learn to be. Average visitors have to work even harder to escape.

Why, if Confederate soldiers almost captured Little Round Top, twice with equal numbers, is it so hard to imagine the Yankees recapturing it soon after with far superior numbers? Why have most writers and historians simply assumed that Confederate capture of the hill meant that Southerners could have not only retained it, but could have also controlled the Taneytown Road, manned supposedly abandoned cannons, raided Union supply trains, and drove one of the largest armies in the world away from Gettysburg? Were early war suggestions that one Confederate could whip twenty Yankees correct? I challenge any of the historians at this conference to point to an instance in the annals of military history in which historians have placed so much faith in soldiers who failed to win than they have placed in the Confederates who never captured Little Round Top.

Tracing the rising tide of Little Round Top’s memory is essential to understanding and making use of its interpretive offerings. The interpretive layers at Little Round Top, both extant and not, are legion and have come in many forms and formats. The layers allow the three-minute visitor and the multi-day heritage tourist to make a connection and understand certain aspects of this small portion of the battle. Even in a biased environment, the savvy student can pick and choose nuggets of information on certain topics while delving deeply into others requiring a closer look.

Today’s interpretive experience provides some measure of insulation from popular history and irresponsible scholarship. Monuments generally denote Union positions and list the deeds of key characters. War Department tablets provide a level narrative for Union brigades and batteries. National Park Service wayside exhibits, as well as those in its visitor center, are measured in their assessment of events on the hill. Some audio touring products succumb to more myths than others. Other touring products, such as the Civil War Trust’s Little Round Top and Devil’s Den “Battle App” allow visitors to delve more deeply into the issues surrounding fact, myth and legend. A multitude of books, booklets, and web sites (most of which support myth and legend over historical accounts) can help visitors before, during, and after their actual trips to the field. The all-but complete lack of Confederate monuments and markers, however, necessarily promotes a partial story, on site. The best way to make up for interpretive failings, bias, or lopsided coverage is through reading in advance of a battlefield visit and by securing on-site tours with Park Rangers and Licensed Battlefield Guides, who can generally and succinctly sort through fact, bias, and myth. Books, apps, audio tours, and guides can address the Confederate side of the story, make history compelling, and bring Little Round Top properly back down to earth. And yet, the tug of the popular story of Little Round Top remains.

Even in preparation for this very conference, the suggestion that we are to examine William C. Oates and Joshua Chamberlain’s controversy above or to the exclusion of other arguments necessarily raises the question of myth and bias. Was I asked to include a discussion of this particular debate as it related to the construction of memory because of its lasting impact upon the memorialization of Little Round Top and Gettysburg or because the popularity of Chamberlain and Oates has made this aspect of postwar argument more well-known and interesting? Why not assess other controversies that affected Little Round Top’s memory, preservation, and interpretation such as the impact of public quarrels between George Meade and Dan Sickles, or Strong Vincent’s statue atop the 83rd Pennsylvania’s monument in apparent violation of Park rules, or the meaning and influence of the missing advanced marker of the 44th New York, referred to on its monument but never installed?

The growth of Little Round Top’s myth and popularity is far from a unique circumstance—this is how history is created, how it evolves, and how it is used and understood. A certain degree of Hollywood-style fantasy and historical exaggeration can be an effective way to get people interested, even obsessed, with historical topics. Partly incorrect information that creates a spark is better than none at all. I’ll take a passionate, misinformed visitor over the reverse any day of the week. Historians can undo a historical mess far easier than igniting the interest and passion--energetic passion--in the first place.

In the long run, we as historians must fight against the gravitational pull of popular history and years of deeply layered historical memory. We might not know everything that happened in any historical event, but we can often determine what did not happen. It is our duty to dispel, rather than participate in, that which is demonstrably impossible. Knowing that we need to do this is an essential part of the future of Civil War history.

Related Battles

23,049

28,063